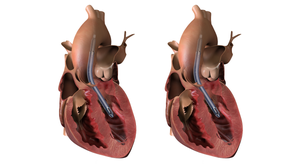

Beating Heart

Cardiovascular

BrioHealth Score IDE Approval for BioVAD System Trial EnrollmentBrioHealth Score IDE Approval for BioVAD System Trial Enrollment

In the study, the device will be evaluated relative to technology that has already been FDA approved.

Sign up for the QMED & MD+DI Daily newsletter.

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)