Addressing the Ongoing Risks of C. Diff in Healthcare Settings

Solutions being explored include modified hand sanitizers, microbiome-based therapeutics, solutions for detecting contaminated surfaces, and more.

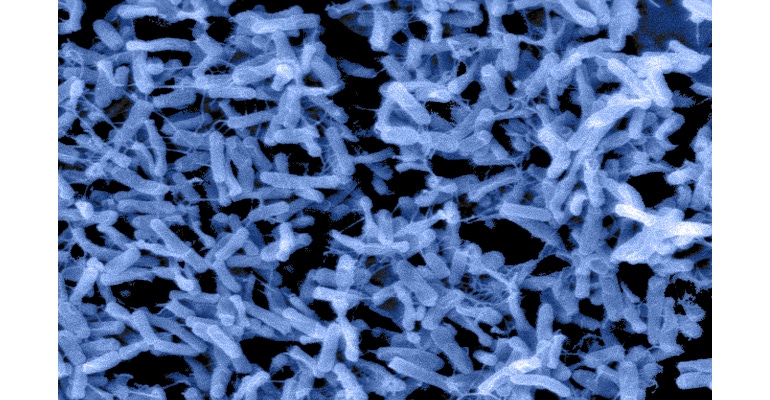

The bacterium Clostridioides difficile, which was formerly named Clostridium difficile and is now commonly known as C. difficile or simply C. diff, is a common microorganism found in the environment. In general, it doesn’t raise serious concerns for healthy individuals. However, some individuals who are taking antibiotics, particularly for long periods of time, experience disturbances in their normal balanced gut flora (microbiota) due to the antibiotics’ inadvertent killing of protective bacteria. This disruption can affect important immunoregulatory and metabolic functions, turning a relatively unnoticed organism into a harmful pathogen, raising serious healthcare concerns. Epidemiology estimates indicate that C. diff causes approximately 500,000 infections per year in the United States, with approximately 29,300 of the infections resulting in death. Given C. diff’s continuing status as a major cause of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), the month of November has been designated C. diff Awareness Month by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

While antibiotic treatment is often the most common predisposition for a C. diff infection (CDI), other risk factors exist. For example, any of the following may lead to increased risk of infection: being 65 years or older, having recently stayed in a hospital, or having a compromised immune system. In these cases C. diff may become an opportunistic pathogen, multiplying rapidly in the gut and producing toxins that cause intestinal conditions, such as diarrhea or colitis. In approximately 3% of healthy adults and 14–71% of healthy babies C. diff may colonize the bowel as part of the normal gut microbiota but will not produce toxins and, therefore, will not cause symptoms.1 But these individuals, who are carriers, are also at a higher risk of progressing to an infection. Once a patient has an active CDI, an antibiotic regimen is the standard care of treatment, but this in turn further disrupts the gut microbiota, resulting in a vicious cycle of recurring CDI that leads to reinfection within approximately 1–2 months for roughly 1 out of 6 patients.

C. diff produces spores that are highly resistant to desiccation (drying), heat, and many disinfectants. This allows the spores to persist for long periods of time on surfaces and then to potentially be transferred onto hands, where they can be spread onto additional surfaces or patients. Community-associated CDI is a serious concern, but healthcare-associated CDI can potentially present a more urgent threat, due to the transfer of other pathogens, in addition to C. diff, from the hands of healthcare personnel to patients.

Although guidelines for management of CDI, especially in healthcare facilities, have been in place for many years, C. diff continues to spread. The recommended preventive measures include frequent hand hygiene using soap and water or hand sanitizers, use of personal protective equipment, cleaning and disinfection of surfaces with effective sporicidal products, and antibiotic stewardship programs. The persistence of CDI transmission in healthcare environments is partly attributed to low compliance with the recommended guidelines and to the lack of an effective approved sporicidal hand hygiene product. Alcohol-based hand rubs (ABHRs), also called hand sanitizers, although recommended for routine use in personal and healthcare settings due to their strong antimicrobial effects against many bacteria, fungi, and viruses, exhibit only limited antimicrobial properties against bacterial spores. Published evidence suggests that modifications of ABHRs, such as acidification to pH 1.2, may produce reductions of approximately 1.5 log10 (or approximately 97%) following use of the ABHRs, a reduction similar to what washing hands with soap and water has been shown to produce.2 As of the 2017 update to IDSA guidelines for medical treatment of CDI, ABHR use for hand hygiene following care of a patient with C. diff is considered acceptable in routine and endemic settings. This is due to benefits of increased compliance relative to handwashing with soap and water and general efficacy in reduction of other common causes of HAIs.3 Thus, incremental improvement of sporicidal efficacy of ABHR, improved compliance of control measures, and innovation of new technologies for sporicidal hand antiseptics would be beneficial in further reducing HAIs.

It is also worth noting that current and novel research involving probiotic treatments, microbiome-based therapeutics, therapeutics to treat effects of C. diff toxins, and even training scent-detection dogs to identify surfaces contaminated with C. diff are also being evaluated.

At BioScience Laboratories, a Nelson Labs company, we have extensive experience growing multiple types of C. diff, designing clinical studies to evaluate the efficacy of hand sanitizers and handwashing products, and evaluating EPA hard-surface-disinfectants. We are happy to support C. diff Awareness Month through our evaluations of the products commonly used for C. diff prevention.

References

Khalaf, N., Cres, J., DuPont, H.L., and Koo, H.L. Clostridium difficile: An Emerging Pathogen in Children. Discov Med. 2012 Aug: 14(75): 105-113. PMID: 22935207.

Nerandzic, M.M., Sunkesula, V.C.K., C., T.S., Setlow, P., and Donskey, C.J. (2015). Unlocking the Sporicidal Efficacy of Ethanol: Induced Sporicidal Activity of Ethanol against Clostridium difficile and Bacillus Spores Under Altered Physical and Chemical Conditions. PLOS One, 10(7): e0132805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132805.

McDonald, L.C., Gerding, D.N., Johnson, S., Bakken, J.S., Carroll, K.C., Coffin, S.E., Dubberke, E.R., Garey, K.W., Gould, C.V., Kelly, C., Loo, V., Sammons, J.S., Sandora, T.J., and Wilcox, M.H. (2018). Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clinical Infectious Diseases, 66(7): e1-e48. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)