Device Tax Could Suck the “Start” Out of Start-Ups

The challenge of raising funds could get even tougher for medtech start-ups. A proposed medial device tax, which is included in both the Senate and the House versions of the healthcare reform bill, could force companies to raise even more capital, says Leslie Bottorff, general partner, medical technology, at Onset Ventures (Menlo Park, CA). The company provides capital to early-stage technology ventures.

January 1, 2010

|

Image courtesy of ISTOCK |

The Senate and House bills propose roughly the same amount of tax on the industry—approximately $20 billion. The Senate would start imposing the tax in 2010 for a 10-year period, according to the J. P. Morgan report, “Medical Supplies & Devices—The 2013 Excise Tax: What it Means to Medtech Earnings,” whereas the House would start imposing the tax in 2011 for a 7-year time period.

|

Bottorff says that the proposed device tax is more onerous for start-ups than larger medical device companies. |

The reasoning behind the delay is that it would give the device industry time to benefit from the expanded coverage that healthcare reform is expected to create. Bottorff says anything that delays the tax burden is good, but an increased volume benefit is likely to help diversified manufacturers in established markets with large market share—not start-up companies that generally have only one product during early commercialization and a small market share.

Proposed exemptions on some Class I and Class II devices also won’t help these early-stage companies. The Senate bill exempts Class I and Class II devices that sell for less than $100, and the House version doesn’t tax devices that are sold at retail stores. This may be good for diversified companies, but for start-ups that primarily manufacture high-tech devices, it means a larger share of the tax burden, Bottorff says.

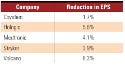

This increased load is illustrated by the J. P. Morgan report. It estimates that if the House version of the tax went into effect in 2013, Johnson & Johnson (J&J) would suffer an 0.8% reduction in earnings per share, whereas NuVasive (a start-up company that went public in 2004) would have a 12.5% reduction (see Table I for more examples). This disparity is partially because Class II and Class III medical devices represent much less of J&J’s sales than NuVasive’s, Bottorff says. Of course, these devices represent about 100% of start-ups’ sales.

Moreover, J&J does more international business than NuVasive, which is revenue that won’t get taxed. Thus, start-ups, which generally don’t have any global sales, are hit much harder by this tax.

|

Table I. (click to enlarge) The predicted effect of the device tax on select companies’ earnings per share (EPS) in 2013. Source: J. P. Morgan estimates. |

Another concern for Bottorff is that the tax is based on revenue instead of profit. Manufacturers that make less than $5 million would be exempted from the tax, and companies that make $15 million–$25 million would pay half the rate—but “that’s not even close to getting these companies to where they are profitable,” Bottorff says. The proposed device tax structure ignores the revenue that is necessary to pay for the infrastructure of a highly regulated, highly scientific company. She says the exemption should be applied to companies that make revenue less than $150 million. AdvaMed also supports increasing the exemption limit. The industry organization recommends that small manufacturers with less than $100 million in annual gross receipts be exempted.

Start-ups depend on investment dollars to cover any expenses in their cash flow, Bottorff says, and “people don’t invest in venture capital for no return.” If a medical device company needs to raise $5 million before it gets profitable to cover the tax, they are going to have the difficult task of generating additional exit value of at least $15 million–$20 million for the investors. She fears this type of math will make it more difficult for investors to justify funding a start-up.

A decrease in the formation of start-ups is a risk for the general population because it means fewer technologies will be invented to treat medical conditions. Healthcare efficiency is mainly improved through technology—not through volume, Bottorff argues.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)