Streamlining the Complaint-Handling Process

In merchandising, customer satisfaction plays a significant role in measuring a product’s postmarket performance. It is also an indicator of how effective the product performance is managed. Both the quality system regulation (QSR) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) require procedures and processes to monitor and control customer complaints. The complaint-handling mechanism not only collects feedback from unsatisfied customers, but also provides means for failure investigations and subsequent corrective and preventive actions (CAPA).

September 1, 2010

|

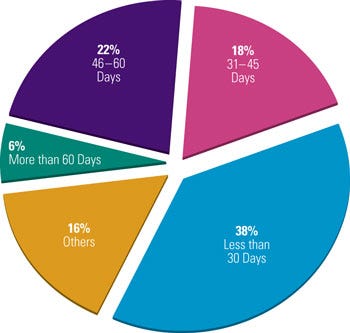

Figure 1. Medical device companies exhibit varying responses to ideal complaint closure time. Strong management support can ensure that closure time is as efficient as possible. |

However, complaint handling is no easy task. Management might overlook the importance of customer feedback and be unable to capture all complaints coming from disparate sources. Plus, the additional regulatory reporting requirement related to adverse events may seem overly burdensome to device makers. A strategic risk-based methodology can help streamline the complaint-handling process in medical device manufacturing.

Regulatory Background

The QSR applicable to medical device manufacturing defines a complaint in 21 CFR Part 820 as “any written, electronic, or oral communication that alleges deficiencies related to the identity, quality, durability, reliability, safety, effectiveness, or performance of a device after it is released for distribution.”1 ISO 9001, ISO 13485, and relevant guidance documents share similar definitions.

In the United States, the rate of innovation and technological advancement greatly accelerated in the 1960s. And by the mid to late 1970s, the new Medical Device Amendments to the 1938 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act had come into full effect. The amendments normalized a device classification system based on risk and market clearance requirements, i.e., premarket approval (PMA) and premarket notification 510(k) application requirements.

In 1990, Congress passed the Safe Medical Devices Act, which emphasized design controls and established the user-reporting system to improve the monitoring of postmarket device safety. This law empowered the agency to recall unsafe devices that might cause death or serious injury. Incidents that occurred on user premises or institutions were required to be documented and reported to FDA. The law also mandated device manufacturers to respond to all adverse events related to the use of their devices. It was a precursor to the later complaint file and device reporting requirements. To strengthen device oversight and control, device makers would be penalized if they were noncompliant with the postmarket surveillance and reporting requirements per the Medical Device Amendments of 1992. During the 2000s, there were several amendments to the Modernization Act that also placed emphasis on postmarket surveillance. Through the use of an electronic data capturing system, FDA’s surveillance program has become more robust, more complete, and more transparent to the public.2

A complaint is an indication of dissatisfaction with device quality or performance, or of a defect after a product has been released for distribution. It is, therefore, an excellent postmarket surveillance indicator. A complaint could lead to repair, servicing, and changes in a manufacturer’s recommendations. A substantial complaint-related failure can lead to recalls and even product seizure. Device failures (or potential failures) do not only refer to a device itself, but also to its labeling and packaging.

Section 21 CFR 820.198 entails the requirements of complaint files. These requirements are related to the general record keeping requirements stated in 820.180. All device manufacturers, regardless of the classifications of the devices, are required to comply with complaint and record requirements. There is no exemption to speak of. Likewise, per the 820.200 requirement, device servicing or repair data must be evaluated to determine whether the failures qualify as complaints or reportable events. In addition, the output of the complaint investigation should feed into CAPA as specified in 820.100.

|

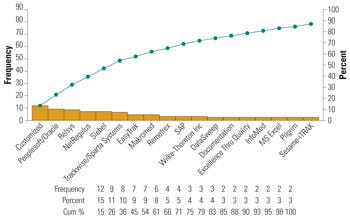

Figure 2. Commercial software commonly used by medical device firms for risk management. |

This chain of regulatory requirements also extends to other parts of the regulation. For example, 21 CFR 803, medical device reporting (MDR), requires that significant device problems be incorporated into FDA’s surveillance system via the MedWatch Form 3500A.3 Decisions for a reportable event are based on three questions, as follows:4

Does the device fail to meet specifications?

Is the device used for treatment or diagnosis?

Is there a relationship between the device and an adverse event?

Manufacturers must notify FDA when they become aware of a death or serious injury that may have been caused by their device. Reportable and nonreportable complaints must be clearly identified and not mixed up during filing. This MDR regulation has been promulgated since 1996 and as of today, companies are continuously having trouble differentiating between reportable and nonreportable complaints. FDA commonly finds significant inconsistencies in companies’ complaint-handling processes.

Common Pitfalls

In 2005, FDA issued 128 warning letters to medical device manufacturers. Among them, 87 (close to 70%) were cited for complaint-handling deficiency.5 Industry experts have concluded through analysis that the three biggest deficiencies the agency flags about complaint handling are as follows:

Inadequate procedures or not following procedures for receiving, reviewing, and evaluating complaints.

Failure to close out complaints in a timely manner.

Disconnect between complaints with adverse events and MDR requirements.

Another challenge is to implement a proper management strategy for tracking and monitoring complaint-handling performance. Poor strategies can lead to overlooked or lost information related to product reliability, raising concerns of public health and safety.

Companies can also be victimized by an inefficient paper-based system to handle customer complaints, which often includes pieces of information brought in from all directions. These sources of complaints are mostly external to the company and are processed internally by different departmental personnel. The typical sources of complaints are telephone calls, e-mails, faxes, letters, company Web site communications, and direct communication with the firm’s sales and servicing representatives.

Although most firms have a complaint procedure in place, it is not inclusive, and not all employees in the organization are sufficiently trained on handling complaints. As a result, customer inputs could be neglected in an employee’s voicemail, data could be lost during transfer to the responsible party, or the loose ends of the complaint outputs might be left dangling because no decision was ever made to close them.

In a quality system, executive management’s support is the key contributor to a successful complaint-handling system. However, for almost 30 years, companies have taken a reactive approach to establishing complaint systems, and often, only after they receive FDA-483s (for observation) or warning letters.

|

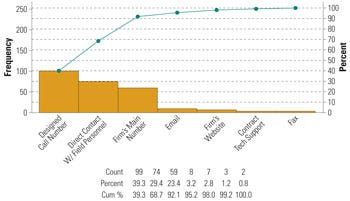

Figure 3. Customer communications methods, by frequency. |

Lack of management support leads to a complaint-handling process that is of low priority in an organization. A survey conducted by Compliance-Alliance in 2006 shows that about 38% of companies take 30 days or less to close out complaints, 40% of companies closed complaints within 31–60 days, and 6% take more than 60 days to close complaints (see Figure 1). When asked about the maximum allowable time for a complaint to remain open, the respondents’ answers varied from 10 days to 3 years.6

Insufficient resources can be another reason for an inefficient complaint closure. According to the survey, there are usually 2–5 employees dedicated to the complaint-handling process. Complaint closure time is tied to the time spent on failure investigation and corrective actions. If a firm’s CAPA system is disconnected from the complaint-management system, it is almost certain that time will be wasted in finding complaint solutions and rationale for closing. A delayed closure may also be caused by an unsuccessful failure investigation, uncertainty about the corrective actions, and of course, the disconnect between the complaint, the failure investigation, and the CAPA process.

An inefficient complaint-handling process can also lead to delays in identifying, evaluating, and communicating an event that may be reportable. Determining whether a complaint triggers the MDR process is always the biggest challenge for device companies and also the biggest concern of FDA.

FDA treats customer complaints as a part of the postmarket product quality and reliability. If complaints reveal any death or serious injury caused by the device or by recurring device malfunction, FDA must immediately take actions. However, FDA citations over the years have indicated that many device companies may have underreported or not filed these events in a timely manner. This MDR requirement is stated in 21 CFR 803 in addition to the complaint file requirement in 21 CFR 820.198. Companies should also follow nonconforming product and CAPA requirements stated in 21 CFR 820.90 and 820.100, respectively. In 21 CFR 820.200, the regulation mandates complaint filing and processing if a repair or service report represents a reportable event. Most field service technicians are not trained to identify complaint and device malfunctions that fall under the MDR decision tree.

Risk-Based Management

An effective complaint-handling process is a management system that ensures the highest level of patient safety, secures the best return of investment, and minimizes product liability lawsuits. In other words, the complaint-handling process is a postmarket quality gauge to measure and control patient, business, and regulatory risk. In a modern quality management system, clear, concise procedures with sufficient details are effective means to maintain quality.

All employees in the medical device firm are compelled to perform their duties according to the company’s standard operating procedures (SOPs) after sufficient training. To tackle the first major deficiency, device manufacturers should designate a unit or group to handle complaints and establish procedures. This group is tasked with the following:

To define the complaint-handling process.

To document the steps to receive, review, and evaluate complaints.

To implement the procedures by proper employee training.

If these SOPs are consistently followed, they enable a standard and uniform complaint-handling process. It is important that a multidisciplinary team is involved when procedures are created and approved. Like all other development processes, the initial implementation requires a learning curve for that given process or task. Well-written and easy-to-follow procedures are the catalyst to this learning process.

Because complaint handling is an integrated process, it is best to break down the complex process into different SOPs that show clear interdependency. Complaint-related SOP categories should include (but are not limited to): customer service and complaint handling, complaint and MDR filing, complaint investigation, MDR, CAPA, product recall, product repair and service, and complaint application software entry. Flow charting the entire complaint-handling process and creating decision trees are useful supplements to the SOPs. Process flow diagrams or decision flow charts are visual aids for more-complex processes.

Once a system and corresponding procedures are in place, most mishandling and misplacement issues can be resolved easily. To tackle the staffing issue, companies are gradually switching from using paper-based systems to semielectronic or fully electronic systems. By switching from paper to digital systems for tracking complaints, companies also experience more-complete documentation, better-coordinated resolution, and a reduction in turnaround time. Although many software applications have been developed in-house, commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) software provides a sophisticated integrated platform to link individual complaints to failure investigations and corrective actions.

Some of these software applications also provide trending analysis and other statistical modeling tools to facilitate a risk-based complaint-handling system. The Pareto chart in Figure 2 represents some commonly used commercial software for complaint handling.6 For complaints coming from different sources, it is important to determine how these are captured and secured into the system. Software is particularly useful in this regard. In addition, management should direct efforts to the common communication channels for information capture. Figure 3 indicates the three most common channels customers use to communicate device-related complaints (i.e., designated customer call center, the firm’s main number, and direct communication with firm’s field personnel).4,6

|

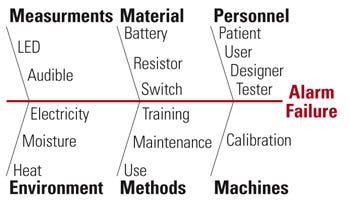

Figure 4. Example of a fishbone diagram showing an alarm failure scenario. |

To streamline the flow of incoming information from customers, a call service representative screens all customer calls, decides whether these inputs meet the definition of complaint, then assigns complaint tracking numbers and enters the information into the complaint-handling system interface. This initial decision point is crucial. If it is done correctly, the company can avoid redundant work in the future or the extra cost spent to fix problems retroactively. After the initial screening and analysis, the quality assurance team should review and approve the initiation of a complaint. Because everyone in the company can be the recipient of complaints, procedural control should be able to direct the different sources to a single processing center, in this case, the customer call service center.

Complaint closure is dependant on a strong failure investigation. The Compliance-Alliance survey reveals that device companies frequently have trouble obtaining sufficient details about the malfunctions or events from device users, company’s sales, or clinical personnel.6 In addition, having customers return faulty devices can be troublesome. If companies cannot accurately troubleshoot the malfunction, find the root cause of a failure, and analyze the risks associated with that failure, it is almost impossible to create and implement sound remediation to prevent recurrence or improve quality.

Firms must introduce an easy method for returning problem devices. For example, they could provide return shipping materials or arrange for a sales representatives to pick up the equipment.5 Customers should also be given questionnaires related to the device failure. Questionnaires have to be user-friendly and in a format that focuses on critical data. These questionnaires are usually divided into three sections to document the product information, patient information, and the complainant information.

A successful complaint investigation requires meaningful analysis. Each event, if it satisfies the definition of a complaint, should be investigated. But the depth of investigation can vary, commensurate with risk. Any exception to this should be adequately justified and that rationale should be documented.

Risk assessment coupled with statistical tools is a new trend in the industry. The ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management (a pharmaceutical document) recommends the use of fault-tree analysis (FTA) to investigate complaints.7 FTA is a type of root-cause analysis combined with probability assessment. This top-down analytical approach evaluates the causes of failure by identifying causal chains of the fault modes and linking them with logical operators (e.g., and, or). This assessment tool paves the way for pinpointing root causes of a failure and their probability of occurrence.8

|

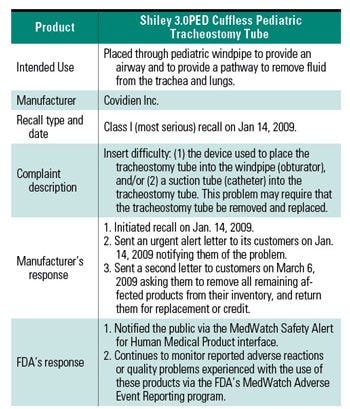

Table I. A example of a complaint-driven recall on Cuffless Pediatric Tracheostomy Tube. |

Another simple and popular tool used by investigators is the cause-and-effect diagram (also called Ishakawa fishbone because its construction mimics a fish spine) to show the main cause categories. Refined causes protrude from each category. Figure 4 depicts a fishbone diagram using the traditional 6Ms categories: manpower (personnel), machines, methods, materials, measurements, and Mother Nature (environments), in analyzing a failure (e.g., alarm).

The drawback of FTA and fishbone diagrams is that they do not assess the magnitude of risks. This limitation can be compensated by coupling them with failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA), a bottom-up approach in which failure is initiated at the component level and can be scaled up to the higher subsystem and system levels.

Hazard analysis is also an effective means to control or eliminate new hazards that are introduced after commercialization. Sometimes experiments are conducted to further evaluate the numerical parameters or settings relevant to the root causes. At one time, industry used a one-factor-at-a-time experimentation method. However, the factorial design of experiment is gaining popularity because this methodology varies all factors in the experiment simultaneously and permits the evaluation of interaction effects.

Trending complaint data helps management detect patterns of failures and evaluate the effectiveness of CAPA. Periodic management reviews and audits serve as the overall effectiveness check of these risk activities. Because no single method can absolutely override the others, integrating multiple tools is appropriate. The tools compensate for the limitations of the other tools and link the different quality units together, which are controlled by the central management system.

Following the same risk-based methodology, quality should be built into the complaint-management system in a controlled manner. If appropriate risk management techniques are being carried out successfully, it is less likely that a significant problem with a device will go unnoticed.

Determining the necessity of a medical device report should be approached by establishing a formal MDR filing system. This system should be separate and distinguishable from the central complaint-handling system, but still retain a close link. Similar to the 21 CFR 820.198 complaint file requirement, 21 CFR 803.18 also requires an MDR event file designation. The determination of a reportable event must be documented and retained in the MDR event file.9,10 These event files can be paper or electronic, but a hybrid approach to documentation is recommended because it creates a backup.

Similar to the questionnaire for capturing customer information, an MDR decision form is useful to streamline the decision-making process on reportable (5-day or 30-day) or nonreportable events. The form also provides documentary evidence to show how a decision is made and therefore, whether an event should be included in the MDR event file.10

From a regulator’s point of view, insufficient adverse-event reporting and follow-up can jeopardize the safety of the general public and put patients at risk. A recent Office of Inspector General (OIG) study shows that 89% of the 140,698 MDRs were filed by manufacturers within the 30-day time frame in 2007; 31% of the 5-day reports, however, were filed late. As a side note, the report also indicated that the agency was unable to review reports in a timely manner because of the high volume of data.11 To address this discrepancy, the agency follows the risk-based approach of prioritization so that incomplete or late MDR submissions are more-closely followed up on than are on-time submissions. The OIG report also suggests that CDRH target its effort to manufacturers that have a history of noncompliance with the MDR requirement.

CDRH is in the process of revising its internal adverse-event reporting system. In August 2009, FDA proposed a rule for electronic MDR (eMDR) to facilitate more-rapid responses to device problems that might lead to serious health issues.12 Industry anticipates a significant redesign and revalidation of the complaint-handling system to accommodate this e-submission requirement.

Both the industry and regulators are responsible for improving compliance with the MDR requirement, which is looped back to complaint handling, failure investigation, and CAPA as integral parts of the complaint management system as a whole. Ensuring customer satisfaction not only favors businesses, but most importantly, reflects how well the patients are protected against nonconforming products. To illustrate the significant role customer complaints play and how manufacturers and regulators respond, refer to the class I recall of the Covidien’s Shiley 3.0PED cuffless pediatric tracheostomy tube on January 14, 2009. A summary of the case is tabulated in Table I.13,14

Conclusion

The act of incorporating risk management into a firm’s quality system has been widely adopted by the device industry. It has explicit instruction in the QSR and is mentioned heavily in internationally recognized guidance documents (e.g., ISO 14971). However, the emphasis on risk-based activities has always been placed on the early design and development phase or only for premarket submissions. Industry often overlooks the iterative nature of risk assessment activities, but new risks always find ways to get into a finished product after it has been in the market for a period of time. A robust complaint-handling process supports postmarket monitoring if a device’s performance feeds back to the quality management system for continuous improvement.

There are several key factors that lead to a successful complaint-handling system. Strong leadership and management support is essential, as is a establishing a complaint unit and cross-functional team. These teams must create well-written SOPs and must incorporate company-wide training. Firms should strongly consider integrated software to automatically manage the process and alleviate employee effort. Effective communication channels must be streamlined to ensure timely information capture.

To accomplish these tasks, many OEMs are opting for a risk-based investigation and remediation process. As industry changes, collaboration with regulatory teams on postmarket surveillance can secure the process to help companies provide safe and high quality medical devices.

References

Code of Federal Regulations, 21 CFR 820.

Josephine C. Babiarz, Douglas J. Pisano, “Overview of FDA and Drug Development,” in FDA Regulatory Affairs, 2nd ed. (New York City; Informa Healthcare, 2008): Ch. 1.

Code of Federal Regulations, 21 CFR 803.

“Medical Device Quality Systems Manual: A Small Entity Compliance Guide,” as of December 2, 2009; available from Internet: www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/PostmarketRequirements/QualitySystemsRegulations/MedicalDeviceQualitySystemsManual/default.htm.

Erik Swain, “Getting a Handle on Complaints,” Medical Device + Diagnostic Industry 28, no. 5 (2006): 84–93.

“Complaint Handling Survey,” Compliance-Alliance (February 2006); available from Internet: www.compliance-alliance.com/free-documents-and-websites/complaint-handling.

Guidance for Industry Q9 Quality Risk Management, ICH Harmonized Tripartite Guideline; available from Internet: www.ich.org/LOB/media/MEDIA1957.pdf.

Richard Fries, “Safety and Risk Management,” in Reliable Design of Medical Devices, 2nd ed., (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2006): Ch. 11.

Barry Sall, “FDA Medical Device Regulation,” in FDA Regulatory Affairs, 2nd ed., (New York City; Informa Healthcare, 2008): Ch. 5.

Medical Device Reporting for Manufacturers; available from Internet: www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm094529.htm.

Adverse Event Reporting for Medical Devices, Department of HHS OIG; available from Internet: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-01-08-00110.pdf.

Mary Houghton, “Device Firms Want Two Years to Comply with Electronic MDR Rule,” The Gray Sheet (November 2009): 1.

Covidien Inc., Shiley 3.0PED Cuffless Pediatric Tracheostomy Tube; available from Internet: www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/RecallsCorrectionsRemovals/ListofRecalls/ucm123848.htm.

Shiley 3.0PED Cuffless Pediatric Tracheostomy Tube by Covidien Inc.; available from Internet: www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm127774.htm.

Trudy Yin is the founder and president of TY Consultants Inc. (Arcadia, CA).

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like