Putting Teeth into FDA Warning Letters

Originally Published MDDI February 2002WASHINGTON WRAP-UP A recent HHS directive seeks to bring about a rational, risk-based approach to enforcement.James G. Dickinson

February 1, 2002

Originally Published MDDI February 2002

WASHINGTON WRAP-UP

A recent HHS directive seeks to bring about a rational, risk-based approach to enforcement.

James G. Dickinson

Keeping FDA's Hands off Internal Audits | FDA's Device Expertise at Risk

How seriously do you regard an FDA warning letter? Does it electrify your company and send the board into shock? For years, Washington lawyers who specialize in FDA matters have been lamenting the failure of FDA warning letters to be taken seriously by companies that receive them.

How seriously do you regard an FDA warning letter? Does it electrify your company and send the board into shock? For years, Washington lawyers who specialize in FDA matters have been lamenting the failure of FDA warning letters to be taken seriously by companies that receive them.

In November, Health and Human Services (HHS) deputy secretary Claude A. Allen, acting in the absence of a permanent FDA commissioner, directed the agency to stop issuing warning letters and so-called "untitled" letters that have not first been cleared for legal sufficiency and policy by the FDA chief counsel, Daniel E. Troy, a new Bush administration appointee.

This immediately provoked an outcry that the Bush crowd was turning the FDA watchdog into a lapdog of industry.

But the man who is credited with having invented these kinds of letters, former chief counsel (during the Nixon administration)—and a candidate for commissioner—Peter Barton Hutt, applauded Allen's move.

"I think it's terrific good news," he told this writer. "Warning letters are chaos now. They are ignored by everybody."

When he started regulatory letters, the precursors of today's warning letters, they gave recipients only two choices—prompt compliance or federal court. "People took them seriously," Hutt said. "Then they gradually began to slide, and FDA began to let more and more people write them. Then, in the late 1980s, FDA took the position that these were so trivial that you could ignore them. . . . If someone sued, FDA said, 'Well, we don't know whether this is our position or not.' Nobody pays any attention to them anymore."

But, devalued though they are from Hutt's era, warning letters have their defenders. Criticism of Allen's action moved the deputy secretary to take the unusual step of answering those defenders. He told me that his motive was not to "chill the impact of FDA enforcement," as some critics had charged.

"What we're talking about," he said, "is having a rational, reasonable, risk-based practice of enforcement. We agree that there are appropriate places for using warnings to industry to let them know what it is that we will be looking at, what we want to enforce.

"But it's also important that we have a risk-based approach, and that means we must lay out our compliance priorities, the outcomes we are looking for, and how we hope to achieve them."

Allen said his directive stemmed from a recent request from HHS Secretary Tommy Thompson. In the continuing absence of a permanent FDA commissioner, Thompson asked him and other senior HHS officials to work very closely with FDA to bring about some "reasoned, thoughtful changes" that would increase the agency's impact in fulfilling its mission."

In the course of this, Allen said he had noticed "some letters come through, and it just raised questions, like, 'What is this?' In the course of a meeting that we had, I raised the question as to what these things were and why they were going out in such a hodgepodge fashion on issues that really have broad implications but may or may not be the highest priority for the agency or the department."

In his directive to acting commissioner Bernard A. Schwetz, Allen related what happened next: "At a recent meeting with the secretary on FDA issues, considerable discussion was directed toward the practice of different components of the agency sending out warning letters and so-called 'untitled' letters that have not necessarily been first reviewed and approved by the FDA's Office of Chief Counsel (OCC)."

This "unleashing of the field" was an innovation of former commissioner David A. Kessler, partly as a means of ratcheting up enforcement and partly as a response to field complaints about long delays in getting FDA clearance for warning letters.

Allen insisted that he does not want his directive to result in such clearance delays now. Indeed, his directive states: "I have urged OCC to review these let-ters expeditiously."

This is all part of building FDA into "the agency of the 21st century," Allen said. The HHS leadership believes the directive will end the current cycle of untitled letters, warning letters, and "recidivist" letters, and in their place lay out a clear road map for industry to follow, with risk-based priorities and standards established by FDA. In doing this, Allen said, "We want to work very closely with our constituencies and stakeholders who are impacted by our decisions. . . . We are looking for FDA to lay out priorities, and enforce those priorities."

As for how FDA will find the resources to do this, Allen said these "may already exist" within the department. He noted that FDA lawyers already "work very closely" with the HHS Office of General Counsel. "We will walk through that as needed," he said.

Keeping FDA's Hands off Internal Audits

Nature abhors vacuums, and governments don't like them either. Consider the regulatory vacuum or no-man's-land that has existed between inspections done by FDA and those done by a company on itself (known as "internal audits").

For years, FDA's position has been to informally encourage internal audits as a good way of keeping companies voluntarily focused on compliance with good manufacturing practices—the theory being that less will be found noncompliant at self-auditing companies when the next FDA inspection comes around. As part of its encouragement, FDA has informally kept its regulatory hands off such internal audits.

That seemed to change in November, however, when FDA released a warning letter it had written to a Florida medical device manufacturer. The letter indicated that the agency had used one of the firm's internal audits as a basis for regulatory citation. Also in November, the Washington law firm of Hogan & Hartson—apparently by coincidence—formally raised the issue of the "hands-off audits" policy in a letter to FDA on behalf of an unnamed client.

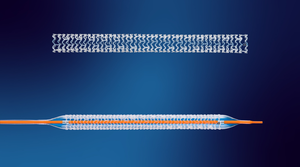

In its warning letter to Medical Device Technologies, dated October 29, 2001, FDA complained that a three-week-old internal audit it found during an inspection at the company's Gainesville, FL, facility had failed to identify quality system regulation deficiencies that were documented easily enough by an FDA investigator. Medical Device Technologies makes catheters and needle sets.

How FDA got the firm's internal audit has not been made public. All a company official would say was that the audit was not provided to FDA. According to the warning letter, other issues raised during the inspection included the company's failure to ensure that quality requirements were being met by its suppliers and contractors. For example, FDA said that the firm's purchasing control procedures did not include all specifications for vendor-supplied devices and that the company failed to require periodic supplier audits. Also, FDA said the firm did not adequately address complaints related to a vendor-supplied product that eventually resulted in a recall.

In its apparently unrelated comments to FDA, Hogan & Hartson told the agency it needs to confirm that a recent draft guidance, Biological Product Deviation Reporting for Licensed Manufacturers of Biological Products Other Than Blood and Blood Components, will not be used to require manufacturers to produce internal audit reports and other audits conducted by clients and contractors that may include possible CGMP violations.

The law firm said the use of these documents would "negate the intent of audit programs or otherwise create a disincentive for manufacturers to be as comprehensive as possible in their scope." According to the law firm, internal audit findings are "relatively insignificant and do not raise concerns about the quality, purity, effectiveness, or safety of the product." Other findings may point out weaknesses or raise potential issues, the letter said, both of which are company methods of demonstrating concern, interest, and diligence in controlling quality and preventing errors. Requiring such documents during inspection may discourage companies from performing thorough self-audits.

FDA's Device Expertise at Risk

Cultural and technological pressures are overwhelming FDA's Center for Devices and Radiological Health and major changes are necessary if science is to continue to play a fundamental role in the center, says a November 16 report by a CDRH external review subcommittee, titled Science at Work in CDRH.

The committee said the center is at a pivotal place in its history—with more than 30% of its staff eligible for retirement; a "woefully inadequate" budget allocation for recruitment, staff training, and development; and an eroding infrastructure in such areas as information systems, laboratory equipment, and training.

"The subcommittee believes that CDRH scientists may become regulators without sufficient scientific training" if the current trends continue for the center, the report stated. Charged by FDA's science board with identifying how science is used within the center, the committee issued its findings based on a review of agency documents and a series of interviews with staff, management, industry, and other relevant parties.

"Significant" changes to CDRH staff recruitment, training, and retention are vital if the center is to remain scientifically competent, the report says. "Additionally, the existing expertise will not be the same expertise that is needed for new technologies. In the discussion with industry representatives, a common theme was that the breadth of existing scientific experience is not sufficient for the future."

The current level of support does not provide CDRH's scientific staff with enough opportunity to remain current within their area of expertise, the report adds, and it says questions exist as to the adequacy of some scientific reviews by scientists hired decades ago who have had little opportunity or time for continued training in their fields.

Additionally, the committee commented on apparent gaps in scientific expertise within the agency. Gaps in neurology, behavioral sciences, and information technology exist, as well as a lack of "human factors expertise and software specialists," the report noted. These gaps point to a need for the center to reach out to other agencies in order to have access to specialized scientific expertise.

Too much emphasis is being placed on the timeline aspect of the center's charge, the report says, and not enough on its long-term needs. For example, some guidance documents are 10 years old and out of date and there are no mechanisms for a systematic review and updating process. Also, management does not appear to have any staffing plan or evaluation of what technical positions are needed to support the center's goals.

Further, "use of outside experts is limited by organizational barriers, budgets, and time constraints, by concerns about confidentiality and conflicts, and by legal requirements for action within restricted time windows. . . . Even when CDRH has expertise within the organization as a whole, the responsible individuals within the Office of Device Evaluation are not necessarily aware that such expertise is present, because they have no detailed database (electronic or otherwise) as a catalog."

The report makes a number of recommendations to the center, including outsourcing functions while still maintaining oversight; establishing an electronic database for liaison functions and an internal and external expertise inventory; assessing the current breadth of expertise and developing a long-term strategic staffing and recruitment plan; and expanding its outreach and scientific interactions with industry and universities. This last component is to be achieved through visitor programs and professional development forums to exchange information between FDA staff, industry, and academia, with an emphasis on scientific fields that will yield new medical devices within the next five years.

Copyright ©2002 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like