Postmarket Surveillance: The Truth Is Never Simple (Part 1—Regulatory Requirements and Data Sources)

In the first installment of this three-part article series, experts detail the requirements for complying with medical device postmarket surveillance regulations and describe potential sources for postmarket data.

December 13, 2016

In the first installment of this three-part article series, experts detail the requirements for complying with medical device postmarket surveillance regulations and describe potential sources for postmarket data.

Kevin Ong, PhD, PE, Michael Frohbergh, PhD, Jennifer Stevenson, Esq., and John Constance, Esq.

Editor's note: This is the first installment in a three-part series detailing the ins and outs of medical device postmarket surveillance. Read Part 2 and Part 3.

As the age of the average American continues to tick upward and obesity-related conditions like diabetes and heart disease balloon in young and old alike, the need for medical devices has surged. Trailing this proliferation of device use in a more diverse and demanding patient population is the significant increase in the risk of product complaints. Even after releasing a medical device onto the market, manufacturers must keep abreast of complaints, not only to satisfy federal statutory and regulatory requirements, but also to ensure that they do not find themselves the target of product liability litigation.

This series of articles summarizes a manufacturer's obligations in complying with postmarket surveillance regulations and details the potential sources for postmarket data. It also previews the future of medical device surveillance and provides guidance to manufacturers seeking to balance their business demands with these strictly regulated surveillance requirements. Finally, the series examines how postmarket surveillance is currently used in litigation and what impact FDA's postmarket surveillance initiatives may have on future legal proceedings.

Regulatory Requirements for Postmarket Surveillance

In the United States, FDA has regulatory requirements regarding postmarket surveillance for the medical device industry. Postmarket surveillance utilizes assessments of products throughout their lifecycle in order to track performance and identify areas in need of improvement or modification. Specifically, the postmarket surveillance requirements include: 1) medical device reporting (MDR); 2) Section 522 postmarket surveillance studies; and 3) postmarket studies ordered at the time of approval (premarket approval "PMA" studies, humanitarian device exemptions (HDE), or product development protocols (PDP)).

FDA requires that manufacturers, importers, and distributors report certain types of product-related complaints in the form of MDRs. Product complaints may involve the identity, quality, durability, reliability, safety, efficacy, or intended performance of a drug product, consumer product, or medical device. They contain large volume, spontaneous feedback, and a direct contact between reporter/patient and call center. This information can be received from any source by an employee who becomes aware of the incident.

Events that must be reported include death or serious injuries that may have been caused by or contributed to by the device, issues requiring the need for medical intervention to prevent or preclude serious injury or death, and malfunctions of the device that, should they recur, could cause or contribute to death or serious injury. Key information that, if available, is reported includes the device information, event dates, detailed descriptions of the event, hospital and healthcare professional information, and patient information. These reports are searchable through FDA's Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) website.

Under Section 522 of the Federal Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act, FDA can order postmarket surveillance of a Class II or Class III device if: 1) its failure may reasonably likely have serious adverse health consequences; 2) it is expected to have significant use in pediatric populations; 3) it is intended to be implanted in the body for more than one year; or 4) it is intended to be a life-sustaining or life-supporting device used outside a device user facility. For example, FDA ordered Section 522 studies of metal-on-metal total hip implants when concerns were raised regarding the effects of metal ions from the implants entering the bloodstream.

FDA may also request post-approval studies as a condition to the approval of a PMA, HDE, or PDP application to help assure continued safety and effectiveness of the approved device. A post-approval study may be clinical or non-clinical and is intended to gather specific information to address questions about the postmarket performance of, or experience with, an approved medical device. FDA and the manufacturer typically reach agreement on the protocols for post-approval studies during the application review process.

Failure or refusal to comply with a 522 order or post-approval study requirements can lead to corrective or punitive regulatory actions, such as product seizure, injunction, prosecution, or civil money penalties.

FDA may also initiate tracking systems, in which manufacturers must adopt methods of monitoring Class II or III devices. The purpose is to ensure that manufacturers of certain devices can promptly locate devices in commercial distribution and remove them from the market and/or notify patients in the event of serious health risks. Devices that meet any of the following three criteria are required to be tracked by the manufacturer: 1) the failure of the device would reasonably likely have serious adverse health consequences; 2) the device is intended to be implanted in the human body for more than one year; and 3) the device is a life-sustaining or life-supporting device used outside a device user facility. FDA maintains a comprehensive list of products that must be tracked.

Postmarket Surveillance Data Sources

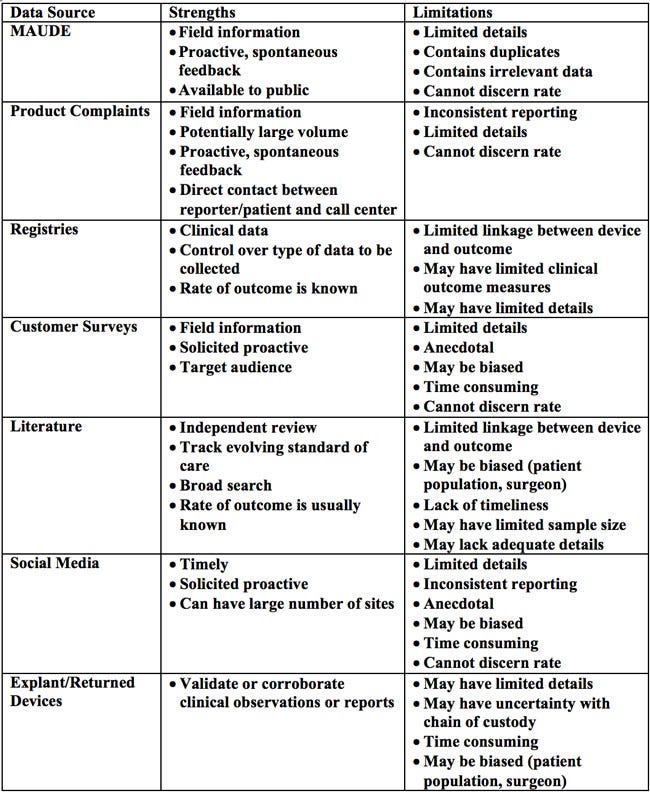

While FDA requires MDRs and may order tracking, 522 postmarket surveillance, or post-approval studies, it is important to recognize the strengths and limitations of these data sources, as well as of other methods for collecting information about the performance of a product. For example, although MDR data is proactive and spontaneous feedback from the field, these data alone cannot be used to establish rates of events, evaluate a change in event rates over time, or compare event rates between devices. They can also contain duplicates and limited and irrelevant information.

Proactive monitoring of product performance using postmarket surveillance resources other than those required by FDA can mitigate risk by providing timely, systematic, and prioritized assessments of product safety. These assessments may then assist the manufacturer in actively identifying potential safety signals. A list of potential data sources is identified in Table 1.

Table 1. Potential data sources for postmarket surveillance

As a regulatory requirement, manufacturers are expected to receive, review, and evaluate complaints. If a complaint indicates a risk of serious injury or death, it constitutes a reportable event that must be submitted through an MDR. Complaints provide spontaneous feedback and a direct contact between reporter/user/patient and call center. Because of the open line of communication and the ability for multiple sources to report complaints, manufacturers can be inundated with a large volume of information, much of which may be superfluous. Moreover, complaints can suffer from inconsistent reporting and issues with event rate determination.

Postmarket surveillance data can also be obtained through registries. Medical device registries are organized systems that use observational study methods to collect uniform data (clinical or other) to evaluate specified outcomes for a population. Registries can be set up by hospitals, manufacturers, medical societies, and government agencies, or as part of a 522 study. They often include data elements such as patient characteristics, hospital/surgeon information, device type, and procedural parameters. However, registries are not clinical trials. Registry patients are observed as they present for care and treatments are not specified, in contrast to clinical trials that have strict protocols and controlled settings, with smaller and homogenous patient groups. Although the registries contain clinical data and allow the determination of an outcome rate within the studied population, they typically provide limited clinical outcome measures and cannot be used to link the device and outcome. Still, registries can provide additional detailed information about patients, procedures, and devices not routinely collected by electronic health records, administrative data, or claims data (described later).

The widespread use of social media serves as another avenue for collecting user feedback on product experiences. Manufacturers can search multiple social media platforms to seek timely field data. However, inconsistent and unsubstantiated reporting is likely, because this information is unilaterally provided by users for non-medical purposes and the users' true identities may be unknown. The anecdotal nature of the information is prone to bias and it can also be time consuming to filter through all the "noise" to realize any relevant details.

Excised/explanted or returned products are physical evidence which, when appropriately analyzed, can help validate or corroborate clinical observations or reports. Yet, depending on what information is provided with the returned product, there may be insufficient patient/clinical details to fully analyze the device. Furthermore, there may be uncertainty with the chain of custody and how the device was handled and/or altered prior to receipt by the manufacturer.

Scientific literature is widely used to inform patients, healthcare professionals, and manufacturers of product performance. The literature should be considered in terms of the hierarchy of study quality. At one end of the spectrum are with randomized controlled trials, the gold standard of scientific research. On the other end are case reports, from which scientific conclusions should not be drawn due to limitations such as small sample size and the possibility of bias. However, no matter the method, a study must be closely scrutinized to determine whether it was appropriately conducted. For the most part, scientific literature is subject to independent peer review and tracks the evolving standard of care. But the advent of pay-to-publish and open access journals calls into question the robustness of the peer review process. Due to the time lag between article submission, peer review, and publication, scientific literature also suffers from a lack of timeliness.

Taking their strengths and limitations into account, these types of data sources can aid in proactive postmarket surveillance.

Kevin Ong, PhD, PE, is a principal engineer in the biomedical engineering practice at Exponent, Inc, an engineering and scientific consulting firm.

Michael Frohbergh, PhD is an associate in the biomedical engineering practice at Exponent, Inc.

Jennifer Stevenson, Esq. is a partner at Shook, Hardy & Bacon, LLP in Kansas City.

John Constance, Esq. is an associate at Shook, Hardy & Bacon, LLP in Washington, DC.

[Image courtesy of CLKER-FREE-VECTOR-IMAGES/PIXABAY]

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)