Startups should heed the Theranos warning: When you raise millions of dollars to develop a product, remember the processes that help get that product to market.

November 18, 2015

Startups should heed the Theranos warning: When you raise millions of dollars to develop a product, remember the processes that help get that product to market, including proper implementation of a robust quality management system.

David Amor

Theranos CEO Elizabeth Holmes

In the medtech industry, there’s an adage about FDA warning letters and 483s: “It’s not a matter of if but when.”

Many reputable organizations have experienced FDA scrutiny and usually emerge stronger because of it. Often, pointing out deficiencies in quality management system elements will lead to remediation and improvements to the company as a whole. Let’s hope media and investor darling Theranos experiences the same results after its recent FDA citation. The blood-testing company was cited for its failure to fully demonstrate that products were validated, complaints were assessed correctly, and the product was cleared for sale.

Theranos, which develops and manufactures lab tests and equipment, promises “smaller needles, smaller samples, a better experience,” with the use of its “Nanotainers,” 0.508-inch containers that are smaller than traditional collection containers. After raising $400 million this year and being valued at just over $10 billion, things were looking up for this fledgling company headed up by enigmatic CEO Elizabeth Holmes, who has been featured as one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people. However, in October and November of this year, Theranos was hit with a double whammy of bad news as a scathing Wall Street Journal article and FDA inspection deficiencies came to light, casting a shadow on the otherwise stunning 2015 successes.

An analysis of the Form 483s issued by FDA suggests the observations are not uncommon in medtech and should remind all medtech professionals about the importance of maintaining a robust quality management system. To clarify, Form 483s are less serious than warning letters and represent an opportunity for companies to remediate product or processes to resolve the deficiencies. Furthermore, it is important to note that these observations and findings are issued after a quality system inspection—not an inspection of the product. Quality system inspections are process audits/inspections that address whether a company is equipped and capable of producing high-quality products in a repeatable and consistent manner.

Let’s review some of the key findings from the Theranos Form 483s. (Note: some observations are redacted and are difficult to read).

Issued 9/16/2015

Design validation is one of the final requirements within 21 CFR 820.30 (the design control regulation) and requires a company to demonstrate that “the right device” was built. Whereas design verification confirms design input requirements (the technical product requirements), design validation ensures the device meets user and stakeholder needs. Design validation in an IVD confirms that the diagnostic effectively distinguishes the disease state or marker as stated in the product labeling.

Typically, these observations stem from poor traceability between the intended use, user needs, and design validation. I recommend that clients use a design traceability matrix that can be input in Excel or another similar format to easily demonstrate how needs were translated into design input requirements and subsequently verified/validated.

It isn’t clear why Theranos was cited here, as much of the data is redacted, but often companies will fail to define the user needs altogether. A key takeaway from this is that there is a difference between what a physician wants and what an engineer is requiring. For example, a physician will likely never say, “The catheter must have a torque force less than or equal to 10 N.” This would be a design input requirement expected from an engineer trying to characterize and translate a physician’s statement of “The catheter must be easy to torque.” As an IVD manufacturer, Theranos use cases were most likely laboratory based, and the intended use was associated with diagnosis of a particular disease state (from using the capillary Nanotainer).

Keeping with the validation theme, FDA above specifies that the “design was not validated under actual or simulated use conditions.” As mentioned previously, design validation is usually the final step prior to design transfer (transferring the design to production). This makes sense; you can’t commit to commercially manufacturing a product until its fully validated to prove that it does what it says it does.

One of the prerequisites for design validation is that your design and processes should be “production ready” and “production equivalent.” In 21 CFR 820.30, it states that “design validation shall be performed under defined operating conditions on initial production units, lots, or batches, or their equivalents.” This means the product you build to prove to FDA that your product works has to represent the product you plan to commercially manufacture, which often means validated test methods, production released parts and components, a design with a bill of materials that represents your commercial product, validated processes, etc. The goal is to reduce the risk that your product fulfills design validation requirements but then fails safety or efficacy benchmarks in the field.

Here’s a tip: Hold a design review prior to design validation, where you lock in the design and processes, demonstrating production equivalence. Perform a gap analysis post-design validation of the product that was used versus the product that was assessed during the design review. They should be the same. Otherwise, ensure your justifications for deviation from production equivalence are technically sound.

We discussed design inputs earlier as being the basis for design verification. Design inputs can be categorized as user needs (Observation 1) and design input requirements (product requirements that are technical and verifiable in nature). Observation 3 is a good example of not fully defining the design inputs and correlating the design inputs back to the intended use.

In Section A, it seems like Theranos failed to test product in all of the configurations defined within its intended use. If an intended use is broad, testing that addresses all possible use cases must be conducted. In Section B, notice that Theranos may have failed to fully specify a requirement in a way that a regulator could confirm that it fulfilled its intended use. Traceability is critical when it comes to design controls, and this observation represents another opportunity for implementing a design traceability matrix. Furthermore, it would be wise for Theranos to specify sources for all design inputs—whether from literature, competitive testing/benchmarking, databases (MAUDE, FAERS, etc.) or otherwise.

Observation 4 addresses risk assessment inadequacies. The top three warning letter QSR parts since 2007 are design controls, corrective and preventive actions, and complaints. What do all three have in common? They are all heavily tied to risk assessment. Critical quality system modules should always incorporate a risk-based approach to decision making. This includes design control.

It isn’t clear why Theranos was cited here, but often companies fail to adequately create a full risk management file compliant to EN ISO 14971:2012. This is the generally accepted standard for risk assessment in medtech and is an FDA Consensus Recognized standard. During submissions, regulators are going to ensure that a form of risk management reporting and activity has been performed. I highly recommend that all companies have an internal standard compliance checklist and ensure that their risk management process is effective and compliant to EN ISO 14971:2012. A standalone FMEA does not represent risk management.

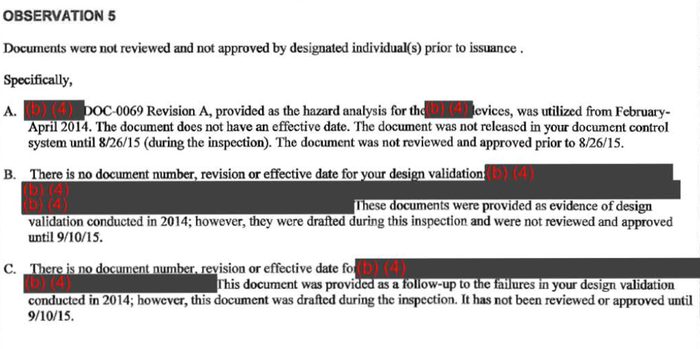

Quality personnel all know the struggle of good documentation practices and document control. Observation 5 is a good example of what happens when document reviews and approvals are not conducted in accordance with QSR requirements established in 21 CFR 820.40 Subpart D—Document Control. This section clearly states that “manufacturers shall designated an individual(s) to review for adequacy and approve prior to issuance” for quality documentation.

In the Theranos observation, a few key findings lead to a cause for regulator concern that quality records are not controlled accordingly. First, there is an inadequate definition of “effective date.” All document control policies should ensure that there is clear distinction between when a document was approved, when it is released, and when it is effective. Often, a document may be approved and released for use, but it isn’t effective until everybody is trained according to requirements established in 21 CFR 820.25—Personnel. Furthermore, these “document states” should have rules that govern revisions, dating, and process for approval/release. Sections B and C in the observation highlight the pitfalls of uncontrolled documentation within a QMS. All key documents must be controlled.

Don't miss David Amor's Regulatory Boot Camp for Medical Device Companies at the MD&M West conference, February 10, 2016, in Anaheim CA. |

David Amor, MSBE, CQA, is a medtech/biotech consultant and mobile health entrepreneur who founded Medgineering, a company focused on remote compliance, regulatory & quality systems consulting for larger companies and start-ups alike. Reach him at [email protected].

Author's note: Thanks to Allison Komiyama of Acknowledge Regulatory Strategies ([email protected]) for her contributions and edits.

[image courtesy of THERANOS]

You May Also Like