Latin American Medical Device Regulations

Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry MagazineMDDI Article IndexOriginally Published July 2000 Until Latin American countries move to a more general, harmonized regulation process, medical device companies wishing to market their products in the region will have to obtain country-specific approvals on a case-by-case basis.Patricia M. Flood

July 1, 2000

Patricia M. Flood

Since the late 1990s, medical device manufacturers have been discovering a wealth of opportunity in Latin America. It is a rapidly growing market where medical device regulations are still evolving. Countries that previously never had medical device regulations are now becoming regulated, and regulated countries are becoming more stringent in their enforcement. These trends will continue. This article summarizes the Latin American regulatory environment, explains the status of medical device regulations and registration requirements by country, and predicts possible changes in the region.

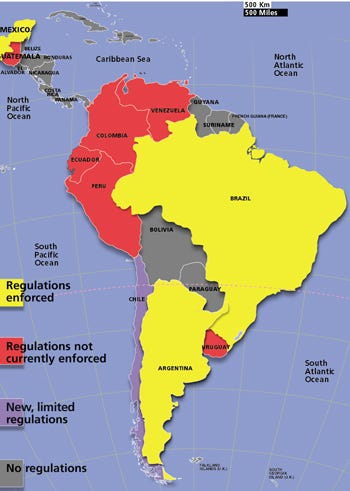

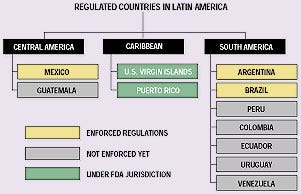

From a regulatory perspective, the countries within Latin America differ (see Figure 1). One group—Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina—has medical device regulations that are enforced. The next group has regulations, but they are not currently enforced. This group includes Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Uruguay, and Guatemala. It is possible to sell products in these countries prior to obtaining product approvals. The third group of countries, which includes the rest of Latin America, does not have any medical device regulations, and it is not necessary to make registration submissions to these countries. Finally, Chile has recently adopted medical device approval regulations (Institute of Public Health, Article 101 of Law No.19.497), but thus far they only apply to certain products, such as surgical gloves and condoms.

Figure 1. Latin American countries with medical device regulations, by area and regulatory status.

Figure 1. Latin American countries with medical device regulations, by area and regulatory status.

PRODUCT REGISTRATION

It is important for a company to be aware of the regulations and comply with them, even if they are not yet enforced. Eventually, these regulations will be enforced; it is beneficial to attempt to register products as early as possible. If a company already has its products registered, commercialization of the products will not be stopped when the country's ministry of health (MOH) decides to require registrations. Very often, foreign MOHs will not "grandfather" products that are already on the market. They may require registrations for all products, even if they have already been sold in that country, unlike FDA, which grandfathered products when the Medical Device Amendments were enacted in 1976.

To register products in a Latin American country, a company must have an office in that country, or it must appoint a local distributor to register products on its behalf. The local distributor must be registered with the MOH.

There are certain benefits to working through a distributor. One benefit is that the distributor has experience working in that region, speaks the local language, and can communicate on behalf of the company. Also, the distributor shares any risk with the company.

There are also disadvantages to working through a distributor, however. Products are registered in the distributor's name, which presents a problem should a company wish to switch distributors; typically, in such cases the products must be reregistered.

Another problem is communication. A company must often rely on its distributors for updates on regulatory changes and other vital information. Often such communications are based on the distributor's interpretations of the new requirements, not necessarily on the facts.

Although products may have FDA or European Commission approval (a CE mark), Latin American countries have their own independent approval processes. Document requirements and approval times vary by country. A Free Sale Certificate (FSC) or a Certificate to Foreign Government (CFG), both of which confirm that a product is approved in the country of origin and can be exported without restriction, are required for all Latin American registrations. The FSC is issued by the MOH in the manufacturing country, if it is not the United States. The CFG, which was previously known as a Certificate for Products for Export, is issued by FDA. Both certificates list the manufacturing site, the specific item numbers, and the product descriptions.

If a company chooses to work through an in-country distributor, a letter of authorization is usually required. The letter simply states that the distributor is authorized to register and distribute a company's product. Many times the distributor will request that terms of exclusivity be stated in this letter.

Usually, the FSC/CFG and the letter of authorization need to be legalized by the appropriate foreign country consulate within the country of manufacture. The consulate applies official seals and stamps to these documents. There are consular services available that will handle the legalization process for a company; this can alleviate a time-consuming task for regulatory personnel who may not have administrative support.

In addition to the FSC/CFG and the letter of authorization, MOHs also require other technical documents and, on occasion, product samples. Table I provides a listing of the specific requirements for each country. Following is a general description of the regulations and registration requirements for each of the major Latin American countries.

BRAZIL

In Brazil, the MOH must control all health-related products. Regulations are strictly enforced. Some products may be exempt from registration, but this can only be determined by the MOH. Medical devices are regulated by Brazilian law #6.360/76, decree 74.094/97. Until last year, the health agency in Brazil was the Secretariat of Sanitary Inspection (SVS). Table I lists the specific documents necessary for a registration submission.

In order for products to be accepted in Brazilian customs, it is a legal requirement for the products to have directions for use in Portuguese and to have Portuguese product labels. Each of the following items must be included:

Product name and intended use.

Manufacturing and sterilization date.

Method of sterilization.

Expiration date.

MOH registration number.

Name and registration number of responsible technical person at the Brazilian distributor's office.

Manufacturer and distributor names (the distributor holding the registration) and addresses.

The typical MOH approval time in Brazil is at least six months, although many companies have experienced longer time periods. This is due in part to the fact that the distributor needs a certain amount of time for the translation of the specified documents. Registrations expire after five years.

The SVS health ministry in Brazil was very bureaucratic. Thus, officials have created a new national health agency known as AGEVISA, which has very similar responsibilities to FDA and the European system. The goal is to remove bureaucracy from registration procedures and expedite approval. This new body began operations in 1999, replacing SVS.

Under the new AGEVISA regulatory regime, importers are required to have an import license for each shipment to Brazil. This requirement was enacted as the result of the trade deficit in Brazil. These licenses will serve to control imports into Brazil and are separate from the manufacturer's MOH registration. An import license, which must be secured prior to importing products, can take four to eight weeks to obtain. The penalty for not having such a license is a monetary fine.

MEXICO

Salud. In Mexico, medical devices must be approved by the Secretaria de Salud (Salud). Registration of medical devices with Salud is by product grouping. If a product line is new for a company, a full registration submission is required. If the product line has already been registered and a company wants to add new item numbers to the registration (new sizes, etc.), however, only the CFG or FSC and an original brochure are required. Certain products (e.g., Foley catheters) are required to meet Mexican standards. Table I lists the specific documents required for a full registration submission. In addition to the listed documents, submissions must include product labels printed in Spanish. These labels must include the following information:

Product name, intended use, and catalog number.

Statement of sterility (if applicable).

Space for registration number.

Manufacturer and distributor names and addresses.

Salud approvals take approximately one to six months to obtain. These registrations are permanent and do not need to be renewed.

IMSS. In order to participate in government bids in Mexico, registration with the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS) is required. The Salud approval certificate must be obtained prior to making a submission to the IMSS. The other specific requirements are listed in table I. IMSS registrations take from six months to one year to obtain; they are valid for a five-year period from issuance.

Only certain products can be registered with the IMSS. Descriptions and specifications for these products are listed in a government book titled Cuadro Básico y Catálogo de Material de Curación y Prótesis. Products must match these specifications to be eligible for government bids. An IMSS registration is more complicated and also more expensive to obtain than is a Salud registration. In addition to the registration submission, actual product samples need to be submitted. Furthermore, the quality control test reports—which correspond to the sample lot numbers—also need to be submitted. Tests are performed on these products to confirm conformance to the company's specifications, as well as to the Mexican standards.

ARGENTINA

Argentina's Ministry of Health and Social Action has delegated the authority of the medical device regulations to the Administración Nacional de Medicamentos, Alimentos y Tecnologia Médica (ANMAT). The medical device regulations were published as Resolution 256/95. Table I lists the specific requirements for a registration submission. The only requirement that is currently being enforced, however, is the presentation of a CFG or FSC. If the product is manufactured in the United States, the CFG is required. If the product is manufactured outside the United States, the FSC from the appropriate country is required. Argentina accepts the CE mark certificate for products manufactured in Europe. A new set of regulations known as Resolution 256 is now pending approval in Argentina.

ANMAT enforces the requirement that all product labels be in Spanish. CE-marked labels can fulfill this requirement. ANMAT also requires companies that import medical devices to maintain an archive of product samples by lot number. These must be kept for six months after the expiration date of the product. ANMAT may perform quality checks on these products.

PERU

In Peru, the medical device registration requirements are fully enforced for participation in bids. For commercialization of products, however, regulations are not strictly enforced. The agency that controls the medical device regulations is the Dirección General de Medicamentos, Insumos, y Drogas (DIGEMID). The regulations were published as Article 110 of the Normas Legales; table I lists the specific requirements for registration.

The FSC or CFG must be less than one year old. They do not need to be legalized, but must be an original. Peru does not accept the former Certificate for Products for Export. Registrations take from three to six months and expire after five years.

COLOMBIA

Currently, regulations in Colombia are not being enforced. The MOH is reviewing registration submissions, however, and granting approvals. The agency responsible for regulating medical devices is the Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos y Alimentos (INVIMA). The regulations were published as Decrees 1292 and 1298. Approvals take at least six months and expire after 10 years.

VENEZUELA

Medical device regulations for Venezuela were published in February 1996. These regulations have not been enforced yet. The health regulatory agency is known as the Oficina de Inscripción Control de Equipos Médicos y Para Médicos (OICEM). Table I lists the specific requirements for product registrations.

ECUADOR

The National Institute of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine is responsible for the regulation of medical devices in Ecuador. These regulations were published in Article 100 of the health code, but have not been enforced yet. The requirements for registration are listed in table I.

URUGUAY

The published law in Uruguay that covers the regulation of medical devices is Decree 338/993. The Ministerio de Salud is the regulatory agency responsible for medical devices. These regulations are still not being enforced; however, the MOH is reviewing product submissions and granting approvals. Approvals take approximately six months and are valid for five years. Table I lists the requirements for product registrations.

GUATEMALA

Guatemalan medical device regulations were published as the Health Registration Law by the Dirección General de Servicios de Salud in July 1996. Currently, there is no enforcement of these regulations. Approvals take approximately two months and expire after five years. Table I lists the specific requirements for product registrations.

FUTURE REGULATORY CHANGES IN LATIN AMERICA

MERCOSUR. MERCOSUR (Mercado Comun del Sur or Common Market of the South) is a free-trade agreement currently in place among Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Bolivia (associate member), and Chile (associate member). This agreement was enacted on January 1, 1995. It eliminated tariffs on about 90% of the goods traded between member states.

Regulatory officials from the MERCOSUR countries have proposed a system of harmonized medical device regulations, which are still under review. At first, each member country will have the same registration requirements, but devices will require approval in each country. Eventually, the goal will be to have approval in one of the countries cover all of the participating countries (similar to the CE mark system). The MERCUSOR regulations will replace any other regulations already in existence. They will also provide a system to ensure that manufacturers comply with quality standards. MERCOSUR quality standards, known as Buenas Prácticas de Fabricación (BPFs), are based on ISO 9001 and FDA GMPs. A regulatory representative from a MERCOSUR country will come to inspect the manufacturing facility and will issue a BPF certificate of compliance. This certificate will be required for registration.

In the proposed regulations, devices will be classified according to intrinsic risk: Class I (low risk), Class II (medium risk), and Class III (high risk). Registration of devices in each class will be mandatory, and registrations will be valid for five years. All labels and package inserts must be printed in the member country's language (Spanish or Portuguese). Devices intended for clinical investigation will be exempt from registration, but must comply with clinical trials regulations.

CONCLUSION

Like other areas of the world, Latin America will eventually move to harmonized regulations. Until then, however, companies wishing to market their medical products in the region must continue to obtain country-specific approvals. It is critical to have good communication channels with the MOHs. When new regulations are issued for review, manufacturers must be able to comment on them and negotiate specific requirements. Staying abreast of changing regulations also will help a company avoid roadblocks in its attempts to market products in Latin America.

Patricia M. Flood is a former regulatory affairs specialist at C. R. Bard Inc. (Murray Hill, NJ).

Illustration by James Schlesinger

Return to the MDDI July table of contents | Return to the MDDI home page

Copyright ©2000 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)