How FDA Dumped Device Secrets in Cyberspace

Abraham Lincoln famously described a “government of the people, by the people, for the people.” But what happens when that government is locked away behind metal detectors and otherwise shielded from easy public view by anonymous gatekeepers in the name of security? Or in the opposite case: when classified information is leaked by the government? In either case, the outcome likely isn’t pretty.

July 17, 2012

Abraham Lincoln famously described a “government of the people, by the people, for the people.” When he uttered those words, he could not have foreseen a government locked away behind metal detectors and otherwise shielded from easy public view by anonymous gatekeepers—all in the name of security. Similarly, Lincoln coulnd't have anticipated how the government can do the opposite: undermine democracy by leaking classified information.

In its recent actions, FDA has both demonstrated how it can be simultaneously secretive and careless with classified information. Image by Flickr user Malakh Kelevra. |

A recent event at FDA reminds us how the agency can do both of these things. As reported by the mass media in July, FDA had dumped medical device company trade secrets onto the Internet where literally anybody could download them. More than 80,000 pages of sensitive computer documents were posted.

It was an accident, of course. One that was discovered inadvertently by an FDA researcher whose e-mails were monitored by the agency. And the exposure of this information lasted, supposedly, only a couple of days—until The New York Times began to make inquiries about it.

As the Times explains, FDA's investigation of its employees in 2010 had evolved into a campaign to counter the claims of those critical of its medical review process.

How did this happen, you ask? Well, from outside those impenetrable walls behind which FDA does its daily business, it’s hard to say for a fact.

The agency’s own version of this story-not independently verifiable, of course-is that while it was preparing its defense to a whistleblower lawsuit filed by former CDRH employees, it outsourced the copying of documents requested by plaintiffs as part of their “discovery” rights to an independent contractor, Quality Associates, of Fulton, Maryland.

Quality Associates proceeded to post thousands of pages of documents related to FDA’s internal email monitoring, including classified company data, on a publicly accessible file transfer site. How this happened hasn’t been revealed but it was presumably an accident.

Not that FDA isn’t perfectly capable of doing the same thing itself. There are numerous incidents from the past of it having done so, including the notorious 1995 case in which a rogue CDRH reviewer sent 128 pages of a competitor’s trade secrets to Summit Technology president and CEO David Muller.

Given the greater facility that technology has given for such accidents to happen in cyberspace, you might be excused for thinking that CDRH, and especially its technology-savvy director, Jeffrey Shuren, would be extremely cautious about outsourcing this sort of work. After all, these aren’t just any old documents that were being copied. There were company trade secrets entrusted to CDRH and protected by U.S. law.

More than that, according to a New York Times exposé and to an interview that FDA counselor to the commissioner John M. Taylor III gave to the Wall Street Journal about this, it was Shuren’s zeal to prevent trade secrets leaking out that prompted him to buy and use high-tech spyware to monitor the numerous CDRH whistleblowers’ private communications. That was an intrusion that provoked the lawsuit against FDA in the first place.

Without the alleged illegal spying, there can be no lawsuit. Without the lawsuit, no need to supply documents under discovery, and no need to outsource that burdensome task to a contractor that then accidentally dumped them into cyberspace.

|

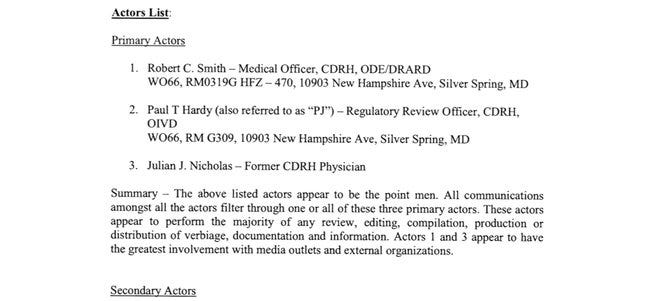

The New York Times obtained an FDA document listing the names of people the agency belives are collaborating in criticism against the agency. |

The Need for External Oversight

This train wreck was predictable long before it occurred. It is the kind of thing that can happen when any agency’s management senses, as FDA’s surely did, that it has no effective external oversight for its internal administrative decision-making, such as purchasing software and hiring employees and contractors.

External oversight is usually focused on the agency’s public activities, such as product approvals and regulatory enforcement. Administrative activities, on the other hand, are often arcane and so stay out of public view, which is where mischief usually begins.

That’s why I have joined many others in the journalism community who have been calling on FDA and other federal agencies to open up their media access policies so that cleansing daylight may be cast on their internal administrative actions, including examining who and why they hire certain employees and outside contractors.

To put the recent behavior of FDA in context, it is helpful to consider the culture of governmental secrecy that has become more prevalent following the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing and especially after the attacks of September 11, 2001. Since those events, stringent physical and electronic security barriers have effectively isolated federal buildings and their occupants, sealing their inner workings from public view. Journalists have had to go through official gatekeepers to reach people they can’t know, instead of cultivating their own confidential sources.

This suffocates the free flow of information and stifles effective external oversight by the news media and others not acting with force of law. Except, that is, on the subject agency’s own terms: We tell you only what we want to tell you, take it or leave it. Absent whistleblowers and other brave dissidents, FDA has become, since it sealed its personnel off from direct public and media access, very good at this.

We probably would not know about the dumping of medical device company secrets in cyber space by FDA’s own contractor were it not for their chance discovery by one of the dissident former CDRH researchers whose e-mails were being monitored.

According to the New York Times, this individual “did Google searches for scientists involved in the case to check for negative publicity that might hinder chances of finding work,” the report says. Within a few minutes, the researcher stumbled upon the database. “I couldn’t believe what I was seeing,” said the researcher, who did not want to be identified because of pending job applications. “I thought: ‘Oh my God, everything is out there. It’s all about us.’ It was just outrageous.”

In a prepared statement, FDA said:

“The monitoring was limited and intended to determine whether confidential commercial information had been inappropriately released to the public. The agency's monitoring was limited to the government-owned computers of five employees and was only intended to identify the source of the unauthorized disclosures, if possible and to identify any further unauthorized disclosures. These steps were taken because FDA, in order to serve the public health of the American people and respect the proprietary interests of the manufacturers, is statutorily required to protect commercial confidential information and trade secrets. The FDA is legally prohibited from releasing this information without legal authorization.

“FDA did not monitor the employees’ use of non-government-owned computers at any time,” the statement continued. “Neither members of Congress nor their staffs were the focus of monitoring. At no point in time did FDA attempt to impede or delay any communication between these individuals and Congress. Employees have appropriate routes to voice their concerns without disclosing confidential information to the public, and FDA has policies in place to ensure employees are aware of their rights and options.”

As for the Quality Associates document dump, FDA said this was unauthorized. “These documents contain legally protected information, and we have initiated an investigation to determine how this occurred. The agency was made aware of the data breach after an inquiry from the New York Times on 7/13. The documents have since been removed and are not publicly releasable. The FDA is looking into this matter.”

Meanwhile, U.S. Special Counsel Carolyn Lerner has issued guidelines for all federal agencies about their monitoring of employee electronic mail and other communications. The guidelines say that although lawful monitoring of employee communications serves legitimate purposes, federal law protects the ability of workers to exercise their legal right to disclose wrongdoing without fear of retaliation.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like