Is This the Key to Better Condoms and Catheters?

July 26, 2017

MIT engineers are working on a new hydrogel that could improve a diverse range of medical devices, including condoms and catheters.

Kristopher Sturgis

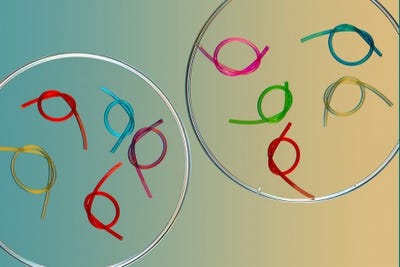

MIT engineering students created a gel-like material to coat standard plastic tubes and rubber devices to ease patient comfort.

When it comes to surgical tubing and intravenous lines, ensuring a safe and comfortable line into the body is critical for the success of many medical procedures. Engineers from MIT hope to make the whole process much easier through the creation of a gel-like material that can be used to coat standard plastic tubes and rubber devices to provide a safe, slippery exterior that can ease the comfort for patients everywhere.

German Parada, a fourth-year graduate student in chemical engineering at MIT and first author on the work, said his team has created several different hydrogels, but the properties of this new gel-like material make it ideal for interactions with living tissue.

"In the Zhao lab we have developed various tough hydrogels and methods to bond themselves to diverse materials," he said. "These gels are soft, contain lots of water, and are very slippery to the touch, which makes them ideal to interface with living tissue due to having similar properties. Last year, we discovered how to attach our gels to rubber and elastomers, then the next step was to apply this discovery to existing medical devices such as catheters, tubing, and condoms. We propose that having this tissue-like material on the surface of devices would improve their performance."

The team is led by Xuanhe Zhao, associate professor in the department of mechanical engineering at MIT. Together, Zhao and Parada began working to bond these layers of hydrogel with various elastomer-based medical devices like catheters and medical tubing, where they found that the coatings added extreme durability to these devices -- enabling them to bend and twist without cracking.

In addition to the added durability, the coating remained extremely slippery, a quality that would undoubtedly reduce patient discomfort. Parada even says that they hope to introduce an anti-infection element to the coating to increase the safety of devices.

"Because of the hydrogel layer, we hope patients will experience much less discomfort when inserting and removing the catheter," Parada said. "If an anti-infection feature is added, we expect a decrease in the incidence of catheter-associated urinary tract infections for people using catheters in a clinical setting. Because of these benefits, we hope this can become the standard coating for all long term urinary catheters."

There's been an increasing focus on the production of medical tubing, with many companies moving toward automated processes that produce some of the world's leading tubing technologies. We've even seen new methods involving heat shrinking to simplify the process, as manufacturers try to produce catheters and other medical tubing that are more durable and reliable than ever before.

However, Parada said no current tubing products contain any kind of hydrogel coating, something that could make all of these tubing products easier to use, while also opening the door to a myriad of other beneficial medical possibilities.

"No product contains an actual hydrogel layer on the surface," he said. "This is unique because without increasing the overall dimensions of the product much, our technology could allow for sensing, drug delivery, and infection control by careful fabrication of the hydrogel layer. This does not yet exist from what we know."

As the group began to test out possible applications for the hydrogel coating, they decided to take their trials beyond just medical elastomer devices. In addition to testing the material on silicone tubing and catheters, they also found that the material is useful on condoms. Their research showed that the gel-like material could help with allergies and other sensitivities when used to coat any of these elastomer devices.

As for the future of the material, Parada said a lot of work still remains with the technology, specifically as they begin to explore adding new features to the material.

"There is a lot of work to be done with this technology, mainly the addition of actual sensing, drug delivery, and infection control features," he said. "Also more studies and trials will be needed to check the level of patient comfort with this technology as compared to existing technologies. And as we mentioned in the study, this could be extended to other rubber-based devices such as tubing, central lines, and even condoms."

Parada said that while the future is difficult to predict, the group remains hopeful that they can work with the MIT technology licensing office and other on-campus entrepreneurship resources to advance the technology and have it ready for patient use as soon as possible.

Kristopher Sturgis is a contributor to Qmed.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)