Managing Foreign Supply Chains to Avoid Importing Risk

Having more partnerships with foreign manufacturers means that U.S. companies must be aware of liability concerns and the safety of imported products.

August 1, 2009

GUIDE TO OUTSOURCING: GLOBAL SUPPLY

|

Illustration by iSTOCKPHOTO |

The global economy has caused supply chains to grow in complexity. Often, the manufacturer or distributor of a finished product is located in the United States, while the companies that provide its component parts or assemble the product are abroad. Managing suppliers and preventing supply-chain failures is particularly important for the manufacturers and distributors of medical devices because of the potential risk that many products pose to their end-users.

While FDA is the designated official guardian of the public health when it comes to overseeing the development, production, and delivery of medical devices in the United States, its power and resources are relatively limited abroad. Several well-publicized incidents involving contaminated products that entered the U.S. market from abroad—many related to food and other consumer goods—have put the spotlight on foreign suppliers as well as the U.S. companies that do business with them. A recent study found that financial executives at top companies believe that supply-chain risks pose the greatest threat to revenue; yet, close to half of the survey respondents said risks associated with globalization and outsourcing are a low priority for their companies.1

Although the public is clamoring for greater government control over foreign suppliers, there are serious product liability concerns associated with supply-chain failures that cannot be addressed by the current regulatory scheme. Instead, it is up to U.S. companies to step up their efforts to ensure the safety of the products they import to avoid costly product liability litigation. This article examines the extent of FDA's control over foreign suppliers, explains the product liability implications of doing business with them, and suggests several strategies for maintaining greater control over the products they provide.

Limited Product Oversight

By law, FDA is required to inspect domestic manufacturers of Class II and Class III medical devices every two years. There is no comparable requirement for the inspection of foreign companies. As a result, only 6% of registered foreign manufacturers are inspected in a given year, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO).2 The GAO further estimates that FDA inspects the foreign manufacturers of Class II devices every 27 years and Class III devices every six years. Domestically, FDA inspects less than 1% of all imports when they arrive at the more than 150 U.S. ports of entry.

Factors Contributing to Low Inspection Rates. The low rate of FDA inspections abroad has been attributed to several factors, including budgetary constraints, language barriers, and hazards and logistical struggles associated with foreign travel. In addition, the GAO determined that FDA relies on inconsistent or unreliable data about foreign companies. Such data can be traced to limitations in FDA's information technology infrastructure, which makes it difficult for the agency to keep track of manufacturers and suppliers located abroad. Additionally, it can be challenging for FDA to exercise authority abroad because it does not have the authority to require foreign companies to undergo FDA inspections.

When a foreign company denies FDA access to a facility, the agency must rely on U.S. import controls as a backstop to allowing the product into the country uninspected.3 In some countries, FDA must first obtain approval from the relevant governmental authority before it may enter a company's facility to perform a foreign inspection. This requirement makes unannounced visits of foreign companies virtually impossible, whereas FDA may conduct inspections of domestic companies without notice.

Recent incidents involving contaminated products by foreign suppliers have put the spotlight on FDA's track record for foreign inspections. To borrow an example from the world of pharmaceuticals, Baxter International issued a voluntary recall of heparin, an anticoagulant drug, as a result of contamination by a foreign supplier. In January 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began investigating clusters of patients who reported experiencing serious allergic reactions and severe hypotension after receiving heparin at dialysis centers.

Ultimately, it was determined that the adverse reactions were caused by a contaminant, oversulfated chondroitin sulfate, a man-made chemical compound, which was introduced into the manufacturing process by a supplier located in China. The contaminated heparin was linked to 81 deaths and 785 severe allergic reactions. At a hearing before the House Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, FDA was scrutinized for failing to inspect the Chinese facility until February 2008, after the contamination had occurred.

Increasing Efforts Abroad. The volume of imports regulated by FDA has doubled since 2003.4 The influx of foreign products, as well as incidents similar to the heparin contamination, have put increasing pressure on FDA from Congress and the public to ramp up efforts abroad. In response, FDA has focused on increasing the number of foreign inspections it performs.

Additionally, it launched the Beyond Our Borders initiative to increase collaboration with its foreign counterparts and enhance technical cooperation with foreign regulators. The initiative has been described by FDA as the first step toward a larger overhaul of the global import safety system.5

In November 2008, as part of the initiative, FDA deployed staff to China to work directly with importers and foreign regulatory agencies and to conduct inspections. It is expected that the agency will spread more than 60 regulators across China, India, Europe, and Latin America by the end of 2009. Ultimately, FDA will likely spend $30 million setting up foreign offices.

Concern over Importer Practices. FDA is also addressing import safety by focusing on the U.S. companies that import the products. In early 2009, FDA, in collaboration with several other U.S. regulatory agencies, issued draft guidance for importers. Titled Good Importer Practices, the document recommends procedures that U.S. companies can implement to ensure that they import only those products that comply with applicable U.S. safety and security requirements. For example, to ensure appropriate oversight of imported products, FDA recommends that a domestic company establish a product safety management program. Along with that, it should develop sufficient knowledge of the regulatory framework that governs the product in its country of production as well as in the United States. The guidance also asks U.S. importers to verify a product's compliance with U.S. requirements throughout the supply chain and product life cycle.

It is important to note that the scope of the guidance is limited. It purports only to assist U.S. companies with importing products that are compliant with applicable U.S. regulations. This means that U.S. companies must identify other possible exposures, such as potential product liability problems, and implement the necessary safeguards.

Product Liability Exposures

Ultimately, U.S. companies may be held responsible for any product liability claims that arise from goods provided by foreign suppliers. When a product causes injury, all members of the product's supply chain are subject to being named in the lawsuit brought by the plaintiff. As a practical matter, the U.S.-based importer of the finished product—the company that puts its logo on the product's packaging—is most likely to be the first party named in the suit. It is usually the party most readily identifiable by the plaintiff. The plaintiff may also bring component part or ingredient suppliers into the suit, if those parties can be identified.

However, the legal complications involved in suing a foreign company in a U.S. court may allow a foreign member of the supply chain to escape being sued altogether. It can be difficult for a plaintiff to serve a foreign company with process—or provide the foreign company with the required legal notice that it is being sued. Therefore, only the U.S. companies associated with the product may be brought into the suit, even though liability may have originated with a foreign member of the supply chain.

In some states, if a product's manufacturer is not subject to service of process, imputed liability statutes provide that the U.S. company that sells the finished product can be sued for the product's defect. That is the law, even if the U.S. company has no direct responsibility for the defect and it played no role in the design, manufacture, or labeling of the product.6 In short, the U.S. importer of a foreign-made product can stand in the shoes of the foreign supplier, because the supplier cannot be brought into the lawsuit. Because U.S. companies potentially bear the burden of litigation, they may be importing liability along with the products they receive from foreign suppliers.

While liability can be created as a result of membership in a supply chain, litigation can be spurred by the public attention that is attracted by problems with contaminated products. For example, following the heparin contamination recall and investigation, the plaintiffs' bar sought to drum up business with an advertising campaign for legal services. The campaign was targeted at patients who claimed to have received the contaminated drug. The same is true for the users of other products that have recently been in the news as a result of problems that originated with foreign suppliers. A simple Web search pulls up numerous sites dedicated to locating these potential plaintiffs. Invariably, the sites implore the alleged victims (or their families) to take immediate action against the U.S. companies that imported the tainted products.

Managing Potential Supplier Problems

Because U.S. companies can be held responsible for the actions (or inactions) of their foreign suppliers, both from a regulatory and a product liability perspective, it is imperative for them to maintain proper control over their supply chains. Namely, U.S. companies must structure their relationships with suppliers to allow them to keep a close watch on the ingredients, processes, and procedures that are involved in the manufacture of the products they import.

|

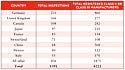

Table I. (click to enlarge) Foreign medical device manufacturers inspected by FDA (2002–2007). The GAO estimates that only 6% of registered foreign device manufacturers are inspected each year. |

Improve Supplier Qualification Practices. During the supplier qualification process, many companies fail to perform basic investigations of their potential suppliers to verify their performance records. A U.S. company should begin by reviewing any information available from FDA and the foreign regulatory body with direct authority over the supplier. The GAO determined that 89% of the foreign inspections that were performed by FDA between 2002 and 2007 were for postmarket purposes (see Table I). The inspections evaluated quality management systems for compliance with good manufacturing practices, adverse-event reporting requirements, and other mandated procedures, or to follow up on specific information that raised questions about particular facilities. If a foreign supplier received such an inspection, the information obtained by FDA can be a valuable part of the due diligence that a U.S. company should request and review prior to doing business with the supplier.

Regardless of whether FDA has performed an inspection, U.S. companies should conduct their own on-site evaluations of supplier facilities. Particularly for critical parts and components, an on-site inspection can help a U.S. company determine whether the foreign supplier has the necessary infrastructure to meet the specific needs of the job. Information, such as certifications and references, which can come from the supplier directly, may also provide valuable information. Inspections must be conducted early in the relationship, preferably before the U.S. company begins importing the product.

Expand the Use of Audit Procedures. The draft guidance on Good Importer Practices advises U.S. companies to audit their foreign suppliers. However, the guidance does not impose legal requirements on U.S. companies (and will not impose legal requirements even after the draft guidance is eventually finalized). Rather, the document states that “readers should view [its contents] only as recommendations.” There is no regulatory requirement that U.S. companies audit their foreign suppliers. From a product liability standpoint, audits of foreign suppliers are necessary to ensure that potential liabilities are not created during the manufacturing process.

U.S. companies should verify with ongoing audits that suppliers continue to meet quality and design specifications. An audit program should be risk based—meaning the extent of the risk associated with the product should determine the audit procedures used to keep tabs on its quality and production. If the potential risk for a product is low, then supplier-conducted surveys (i.e., self-audits) may be appropriate. For higher-risk products, U.S. companies will often use independent third parties to assess the product. In some instances, a U.S. company may choose to locate personnel in the foreign supplier's facility to oversee critical operations.

Verify Supply Chain Integrity and Safety. Too frequently, U.S. companies fail to investigate the length of their supply chains. Instead, they examine only the link that is immediately below them, the foreign suppliers that ultimately export the products to them. It is important for U.S. companies to verify that each link in the supply chain is compliant with good manufacturing practices and provide quality products. Following its inspection of the Chinese facility involved in the heparin contamination, FDA issued a warning letter to the facility for its failure to keep tabs on its suppliers, among other violations. In the letter, FDA stated, “Your system for evaluating suppliers of crude heparin material is ineffective to ensure that materials are acceptable for use.…Suppliers should be monitored and regularly scrutinized to assure ongoing reliability.”

FDA's findings were consistent with the results of Baxter's own investigation, which determined that the contamination originated not with the Chinese facility that immediately exported the crude heparin to Baxter but with its supplier's supplier, somewhere down the supply chain. Given the nature of U.S. product liability law, which holds the U.S. importer responsible for injuries that originate anywhere along the supply chain, it is ultimately the responsibility of the U.S. importer to verify the integrity and safety of all of its suppliers.

Sidebar: Regulatory Liability Arising from Supply Chains |

Shifting Risk Back to the Supplier. One of the most important things a U.S. company can do before it does business with a foreign supplier is to negotiate and enter into a contractual agreement. The very act of negotiating the contract is important to ensuring that both parties—the U.S. company and the foreign supplier—understand the requirements and specifications of the job. Among other things, the contract should name the party that will be responsible for recalls and other postmarket activities, the insurance requirements that each party must meet, and the quality requirements that the supplier must meet. Also important is the type of notification (i.e., when and how) the supplier will provide to the U.S. company any change to its manufacturing processes or component parts or ingredients.

A U.S. company may include a cooperation clause in the contracts, which requires the foreign supplier to cooperate with any investigations conducted by the U.S. company or FDA. Finally, it is important to include an indemnification agreement in the contract, which may enable a U.S. company to shift risk back to the foreign supplier. A foreign supplier that agrees to indemnify a U.S. company becomes contractually liable for any damages that arise from the products it supplies.

How the parties structure their agreement depends on the unique facts involved, which underscores the need for parties to seek legal assistance when negotiating these agreements. In particular, U.S. companies should seek legal assistance from attorneys who are experienced in drafting contracts between multinational parties; agreements may involve foreign laws. As noted previously, it can be challenging to bring a lawsuit against a foreign company. An experienced attorney can help a U.S. company draft a contract that can be enforced successfully in a U.S. court. Sometimes, a foreign supplier's connections to the United States can be surprising. Depending on what preexisting relationships a foreign supplier has with other U.S. companies, it may be easier than it first appears to negotiate and enforce a contract with a foreign supplier.

Conclusion

A U.S. company should not wait for FDA to enhance its authority abroad before it begins to exert greater control over its foreign suppliers. The product liability threats that lurk in supply chains are reason enough for U.S. companies to step up their oversight efforts. In general, a U.S. company must seek greater transparency in its relationships with suppliers. That can be done through enhanced supplier qualification and audit procedures that cover the length of the supply chain and contracts with its suppliers. The product liability costs associated with supply-chain failures justify making these oversight activities a top priority for U.S. companies.

Sara E. Dyson is loss control manager for Medmarc Insurance Group (Chantilly, VA).

References

1.“Managing Business Risk in 2006 and Beyond,” FM Global and Harris Interactive Inc., September 2005.

2.M Crosse (director of healthcare, Government Accountability Office), “FDA Faces Challenges in Conducting Inspections of Foreign Manufacturing Establishments,” testimony before the Subcommittee on Health, Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives, May 14, 2008.

3.A von Eschenbach (FDA commissioner), testimony before the Committee on Energy and Commerce, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, House of Representatives, November 1, 2007.

4.“FDA Beyond Our Borders,” FDA Consumer Health Information, FDA, December 9, 2008.

5.“Leavitt: Regulation-Building Is Key Role of New FDA Foreign Outposts,” in FDA Week, vol. 14, no. 42 October 17, 2008.

6.E Zalud and C Taft, “Tracking Foreign Manufacturers to Obviate Liability,” in For the Defense, December 2008.

Copyright ©2009 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like