R&D DIGEST

August 1, 2006

|

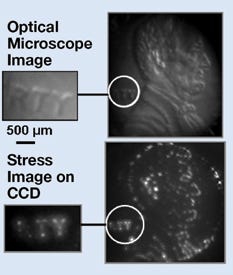

An experiment conducted by Ravi Saraf shows that the nanothin sensor can detect very fine features (bottom) better than current technologies can (top). |

A thin film that mimics the sensitivity of human skin could be used to perform minimally invasive surgery. Chemical engineer Ravi Saraf from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln led the development of the film. Saraf says the film could help surgeons understand the texture of tissue encountered during minimally invasive surgeries. “Touch is an important sense that has been missing from this type of surgery,” Saraf says. “Incorporating it could lead to detecting precancerous cells before they become malignant.”

To make the sensor, researchers deposited alternating layers of gold and cadmium sulfide nanoparticles, separated by insulating layers of polymer that are about 2 or 3 nm thick, to create a 1-cm2 piece of film that measures 100 nm thick.

The device is attached to electrodes that control a current flow. When the film is pressed to a surface, the stress distorts the polymer layers so that electrons tunnel through them to the cadmium sulfide particles. The electrons make the particles glow with increasing brightness as pressure increases. Saraf says it's a simple principle that is used regularly in television technology.

To demonstrate, the team used a penny and set up a camera to monitor the glow. They showed that the film could distinguish the contours of Abraham Lincoln's head and the letters t and y in Liberty. Saraf and graduate student Vivek Maheshwar published an article covering the experiment in the June 9, 2006, issue of Science magazine. The article reports that the sensor can detect surface detail with a pressure of about 9 kPa. That pressure is similar to what humans use to feel and pick up objects. The film can detect features as small as 40 µm wide, which is 10 times more sensitive than sensors currently on the market.

Although there are numerous applications for the technology, Saraf is mainly concerned with improving cancer detection. “There are two options for monitoring with this sensor: optical and electrical,” says Saraf. He believes the optical option may be most beneficial for identifying cancerous tissue. He explains that cancerous tissues, especially those in the gastrointestinal tract, are often harder than regular tissue. Therefore being able to distinguish texture could help surgeons identify cancer cells.

Saraf and his team are trying to develop a device that makes use of existing endoscopic monitoring and superimposes touch data gathered by the film. “Because the film is so thin, it is almost transparent,” Saraf says. “It could easily go over the tip of an endoscope.” An endoscope-imaging monitor could be adapted to show the film's phosphorescence and let surgeons know the texture and hardness of the tissue.

The next level of development, he says, is to make the device biocompatible. “We still have to work out the issues of making the device bioinert, but because all the materials we use are very common, I think it can be done.”

Saraf estimates that he could have a prototype ready for testing very soon, but is actively looking for funding to continue refining the device design. “It's a question of resources. But the engineering could be done in the next year,” he explains.

The Office of Naval Research and the National Science Foundation supplied initial funding for the development of the sensor film.

Copyright ©2006 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like