State of the Union: Drug-Device Combinations

The challenges of creating a drug-device product are etched in the cultural differences between pharmaceutical and device manufacturers. Overcoming these obstacles can lead to lucrative partnerships and innovative products.

November 1, 2006

REGULATORY OUTLOOK

|

Many medical device companies are accustomed to entering into partnerships and collaborative arrangements with other manufacturers. However, these arrangements can present regulatory, financial, commercial, and logistical problems even when both firms are device makers. And the complexities multiply dramatically when one partner is a pharmaceutical company.

Collaborations between drug and device companies have grown significantly in the last few years. These partnerships have produced a variety of products, such as drug-eluting stents, drug-delivery systems, antibiotic-coated orthopedic implants, and copackaged drugs and devices. They have also produced cross labeling between drugs and devices, e.g., diagnostic products used in conjunction with drugs.

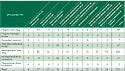

FDA's Office of Combination Products (OCP) reported that 40 requests for designation (RFD) were submitted in 2005, a 25% increase over 2004 (see Table I).1 Collaborations are likely to continue to increase, as exemplified by the new agreement between FDA, the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services involving oncology drugs and biomarkers.2

The device-drug relationships can be very profitable to device companies; drug-eluting stent sales have rung up billions of dollars in sales annually. Yet, for these relationships to succeed, device companies must appreciate and navigate many hurdles unique to partnerships with pharmaceutical companies. Only by identifying and addressing some of the associated regulatory and commercial issues can manufacturers successfully create combination products.

A Tale of Two Cultures

Both devices and drugs (including biologics) are regulated by FDA. There are many areas of parallel regulatory requirements, but the regulatory regimes that apply to these two industries differ in fundamental ways that, if not recognized and appropriately handled, can cause significant complications. Indeed, CDRH recently identified some of the differences, saying, “Innovation for medical differs from innovation for pharmaceuticals. Device innovation includes both giant leaps and incremental changes with life cycles as short as 18 months.”3

A device company that is about to embark on a partnership with a drug company must appreciate from the outset that the partners will have different perspectives. If a U.S.-based device company is considering a deal with a foreign company, both sides know that there will be some cultural differences. It is not entirely far-fetched to suggest that a device company should view a potential drug partner as though it were from a foreign culture.

|

Table I. FDA gave preliminary categorization as combination products to 251 original applications under review during FY 2004. |

One major difference between the two types of products is that drugs take much longer to reach the market. From the time a drug enters preclinical studies to the time FDA approves a new drug application (NDA), 10 years or more can elapse. Drug companies are accustomed to such long-term planning; device companies are not. Even if the collaboration begins during a drug's phase 2 trials, it may be years before the drug product is approved. Devices can go through several generations in the time a single drug moves from R&D to approval.

Another aspect to consider is that the probability of success for drugs is much lower than that of devices. According to FDA's statistics, only about 8% of drugs that start phase 1 trials get approved and 1 of 1000 compounds that enter preclinical testing reach the clinical study stage. Although FDA's Critical Path Initiative and new phase O option (for early clinical testing with low doses) are intended to improve the odds, it will take years for the benefits of these programs to be felt.4,5 Not all devices that are developed make it through the FDA process, but drug companies face far more daunting odds. Therefore, in early-stage collaborations with drug companies, device manufacturers must take into account longer timelines and lower probabilities of success for their partner's product. If the drug is already marketed and only an NDA supplement is needed (e.g., approval for a new intended use), these differential factors diminish but they do not vanish.

Drug companies also face a much more costly development program. Tufts University (Boston) estimates that pharmaceutical companies spend more than $800 million for each approved drug.6 These calculations can be and have been challenged by critics (they include the costs of failed studies), but there is no disputing that the drug approval process is extremely costly, far more so than for virtually any device.

Because of these and other considerations, drug companies face different financial structures. Until recently, drug companies focused on so-called blockbusters, i.e., drugs with sales exceeding $1 billion annually. Many drugs have hit that target, while few devices enjoy those kinds of stratospheric sales. Even drugs considered poor sellers may exceed $100 million in sales—a much higher level than the vast majority of devices—and yet in some cases still be a disappointment. For small biotechnology and drug companies, the economic considerations can be very different. Therefore, the financial calculations for returns on investment can be very different for the device partner than the drug partner. That means the needs and expectations for both sides can be quite divergent.

Another difference is that once approved, drugs can remain on the market for decades unchanged. Meanwhile, rapidly advancing technology and continuing product modifications characterize the device industry. Static devices are prone to obsolescence, but older drugs can retain healthy profit margins. As one ex-FDA official stated, “If you're not developing a [device] continuously, you're going to go out of business.”7 In part, this ability to change is facilitated by the different regulatory constraints. Drug companies have very little latitude in making product or labeling modifications without getting FDA approval. There is no counterpart in the drug regulatory scheme to the flexibility enjoyed by 510(k) holders to modify products or labeling.

Misunderstandings may even be exacerbated by the seeming commonality of regulatory framework. For example, both types of companies are subject to good manufacturing practices. Hence, the two sides may think that when they discuss GMPs, their partner has the same meaning in mind. A drug company that is told its device partner is in full compliance with GMPs may find that some drug GMP requirements (e.g., stability testing and returned product) are missing. Conversely, the drug GMP regulation does not have counterparts to design controls and corrective and preventive actions. More fundamentally, the drug company may be surprised at the physical appearance of a device manufacturing facility. To someone with years of pharmaceutical experience, device manufacturing plants may not look like GMP-compliant facilities.

The basic point is simple and important: drug and device companies, while sharing a common regulatory agency, some similar regulatory constraints, and even some overlapping regulatory vocabulary (e.g., registration and misbranded), may enter into negotiations with fundamentally different needs, perspectives, and expectations. These differences need to be kept in mind when device companies begin talking with potential pharmaceutical partners, when negotiating an agreement, and once the companies commence their collaboration.

Despite these obstacles, drug and device companies often find common ground that makes partnerships valuable. The device industry is fiercely competitive; many segments have multiple players battling for sales. This is also true in the drug industry. Pharmaceutical companies will aggressively fight for market share in a particular field, such as cholesterol-lowering agents or attention deficit drugs. However, the drug industry faces a challenge largely absent for device companies—competition with generics. Once a drug goes off patent and loses any other exclusivity under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, generic competition can begin. A drug can lose 80% of its sales within the first year of generic competition. This financial reality and the imperative to ward off generics may motivate drug companies to seek out collaborations with device manufacturers. If, through the use of a device, the drug manufacturer can develop a new intended use or modify the product, under the Hatch-Waxman Act this may yield additional time on the market before the onset of generic competition. Receiving three years of exclusivity can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

Once the decision has been made and the culture clash has been addressed, companies must address the practical side of regulation together.

Who Regulates the Product?

Whether there is even a need for regulatory collaboration is something of a threshold question. An open regulatory issue is how FDA should regulate devices that are intended to be used with drugs when there is no desire or need for company cooperation. Sometimes it is enough for each firm to market its own product independently of the other. Yet regardless of how much latitude FDA grants in these circumstances, there are still situations in which drug-device collaboration is necessary.

One of the principal issues that must be addressed for a drug-device collaborative project is determining which FDA center regulates the product. Because devices and drugs are regulated so differently, this question must be resolved at an early stage.

In many cases, the regulatory framework for a combination product is established by precedent. Drug-eluting stents are regulated as devices while a prefilled syringe will be regulated as a drug. The responsibility of regulation becomes less clear when the product is of a new type.8 Although FDA's regulations for determining the primary center provide some useful additional clarity, ambiguities remain.9 Moreover, jurisdiction may not be preordained—it often depends on the product configuration or claims.

Through the submission of an RFD to OCP, the mechanism for obtaining a binding answer as to the primary center is straightforward. OCP will respond to an RFD within 60 days. Of course, RFD submission is a bit more complex than this article covers. Lack of planning could lengthen the approval process. If there is any doubt as to which center will exercise primary jurisdiction, it is much better to find out at an early stage. Companies should not wait until after they have submitted a 510(k) premarket notification to learn that a product is going to be regulated as a drug. However, before an RFD can be submitted, the collaborators must answer the following questions:

• What is the product?

• What is the product's intended use?

• How do the parties want the product to be regulated?

• What is the jurisdictional objective of the collaborators?

• Which company will control the regulatory process?

First, companies need to decide what the product is. Should it consist of a device and drug sold separately with cross labeling, or should it be sold together in a box or as a single unit comprising drug and device? Companies that are unable to answer these questions must have a plan for how and when they will decide. Until that is done, parties are not likely to know if they are seeking to market a drug, a device, or one of each. And until the product configuration is defined, it can be very difficult to determine which center will have primary jurisdiction.

Second, the companies should define the product's intended use. Regulatory jurisdiction sometimes can hinge on relatively minor word choices. For example, an antibiotic-coated orthopedic implant may be regulated as a device if the intended use of the antibiotic is to prevent colonization on the implant. The same product with a claim that the coating prevents infection might be classified as a drug.

Defining intended use at an early stage can be difficult enough for a device or drug company developing a product on its own. Sometimes the intended use cannot be determined until after clinical studies have been completed and the product's utility is better understood. The difficulties can be magnified if companies approach the problem with different regulatory viewpoints. Such challenges can be further exacerbated if the companies have different and unstated expectations of what claims they want to make for the product. Many device companies that have developed their own product do not define at an early enough stage the expected intended use. Agreeing on that essential element can be much tougher when two companies have disparate perspectives.

Third, the parties need to agree on how they want the product to be regulated. Regulation as a device generally is considered advantageous from a regulatory perspective. Yet, a drug company may prefer drug regulation because that is the regulatory scheme it knows. Or there may be statutory provisions unique to drugs that favor pharmaceutical status, such as the Orphan Drug Act, which provides market exclusivity for the drug and tax breaks, or Hatch-Waxman exclusivity. 10,11

Companies also need to assess the potential effect of regulatory classification on reimbursement. Medicare, Medicaid, and other third-party payers reimburse drugs and devices differently. The new Part D Medicare benefit, which deals with drugs, can add another wrinkle to the evaluation of regulatory pathway. Indeed, assumptions regarding the reimbursement framework may be contained in the potential partners' assessment of the potential return on investment. The companies, however, would be well advised to explicitly discuss this factor at the outset as they analyze the implications of FDA's jurisdictional decision.

It's important to decide the jurisdictional objective early and appreciate the implications of that approach. The regulatory body informs product development and clinical studies. Although precedent often determines the regulatory status of many combination products or collaboratively sold drug-device products, companies can also affect a product's status. Sophisticated companies seeking device classification will take that objective into consideration as they develop their marketing plans, clinical strategy, product composition, and regulatory submissions. The entire clinical and regulatory program, as well as time to market and clinical costs, will be dramatically affected if the goal is to have the product regulated as a drug (e.g., prevents infection) instead of a device (e.g., prevents colonization).

Fourth, the parties need to agree on who will control the process of determining regulatory status, including submission of an RFD. Although the companies may certainly commit to consulting each other and the nonsubmitting party may contractually insist on the right to review the RFD, ultimately one company needs to take the lead and be responsible for filing an RFD. Similarly, the companies should consider the allocation of responsibilities for creating and executing reimbursement strategies.

The agreement should determine which company has such power. Firms should also consider how to address potential follow-up issues, such as who will attend FDA-requested conferences to answer RFD questions or who will participate in telephone calls with OCP. If the device company delegates all responsibility for the RFD process to its partners, it may have no ability to influence this key process.

Conclusion

There is no legal or regulatory requirement that drug and device companies need to consider product jurisdiction and related commercial issues before signing an agreement. In some instances, the roles of the respective parties will be well understood based on FDA regulations. However, collaborations improve if these issues are addressed in advance.

Understanding the different cultures and goals and then developing a plan to identify and resolve product jurisdictional issues will greatly improve the odds of a successful association.

Jeffrey Gibbs is a director at the law firm Hyman Phelps & McNamara (Washington, DC) and can be reached at [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Mark D Kramer, “Combination Products: Challenges and Progress,” Regulatory Affairs Focus (August 2005): 33.

2. Federal Register, 71 FR:E6-01918, February 13, 2006.

3. Medical Device Innovation Initiative, (Rockville, MD: FDA, CDRH, May 2006).

4. Critical Path Opportunities Report (Rockville, MD: FDA, 2006).

5. Federal Register, 71 FR:06-354, January 17, 2006.

6. Joseph DiMasi et al., “The Price of Innovation: New Estimates of Drug Development Costs,” Journal of Health Economics 22 (2003): 151–185.

7. United States v. Gugnani, 1768 F. supp. 2d 538 (D.Md.), Trial Testimony of Robert Sheridan (August 21, 2000).

8. David M Fox and Jeffrey K Shapiro, “Combination Products: How to Develop the Optimal Strategic Path for Approval” (FDA News 2005).

9. Federal Register, 70 FR:05-16527, August 25, 2005.

10. Orphan Drug Act, 21 U.S.C. sect. 360

(aa)–360(ee).

11. Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, 21 U.S.C. sect. 355.

Copyright ©2006 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)