Kurzweil on Why Medicine Is Undergoing a Grand Transformation

February 12, 2016

Your smartphone is as powerful as a supercomputer from yesteryear. But 25 years from now, computing systems will be one billion times more powerful and 100,000 times smaller, said famed futurist Ray Kurzweil. The implications for the practice of medicine are mind boggling.

Brian Buntz

.jpg?width=400&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) In the mid-1990s, researchers involved in the Genome Project announced that they had completed one percent of the human genome after seven years of work. Mainstream critics complained that finishing the project could take 700 more years. "That was linear thinking. My reaction at the time was: 'Oh, we've finished 1%--we are almost done because 1% is seven doublings from 100%." The sequencing of the first genome was completed seven years later, explained Kurzweil at a keynote at MD&M West in Anaheim, CA. The field of genomics, like all information technologies, follows an exponential growth pattern, he explained.

In the mid-1990s, researchers involved in the Genome Project announced that they had completed one percent of the human genome after seven years of work. Mainstream critics complained that finishing the project could take 700 more years. "That was linear thinking. My reaction at the time was: 'Oh, we've finished 1%--we are almost done because 1% is seven doublings from 100%." The sequencing of the first genome was completed seven years later, explained Kurzweil at a keynote at MD&M West in Anaheim, CA. The field of genomics, like all information technologies, follows an exponential growth pattern, he explained.

Information technology has developed at an exponential clip since as far back as the 1890s. And it will continue to do so after Moore's Law dies, he declared. When Intel co-founder Gordon Moore observed in 1965 that the number of transistors on integrated circuits doubled roughly every 12 months, the so-called law has been used to track technological progress ever since, although some pundits have been declaring that relevance of the law is waning.

"This exponential growth started decades before Gordon Moore was even born," Kurzweil said. "People have been saying for a long time: 'Oh, Moore's Law is going to come to an end,' which it will in 2020. The key features then will be 5 nanometers, which is the width of 20 carbon atoms."

The limits of chip-based computing technology now echos what happened with vacuum tubes in the late 1950s. Vacuum tubes were getting considerably smaller each year, but then scientists hit a wall in 1959. "We couldn't shrink the vacuum tubes anymore and that was the end--of the shrinking of vacuum tubes. It was not the end of the exponential growth of computing. We just went to transistors and then to chips," Kurzweil said.

After Moore's Law dies, we will go to the next paradigm, computing in three dimensions. "Our brains are organized in three dimensions, which is really one key source of its power," Kurzweil said.

The sequencing of the human genome has transitioned the practice of medicine into an information technology as well, which means that it will follow a similar exponential growth curve as other technology sectors.

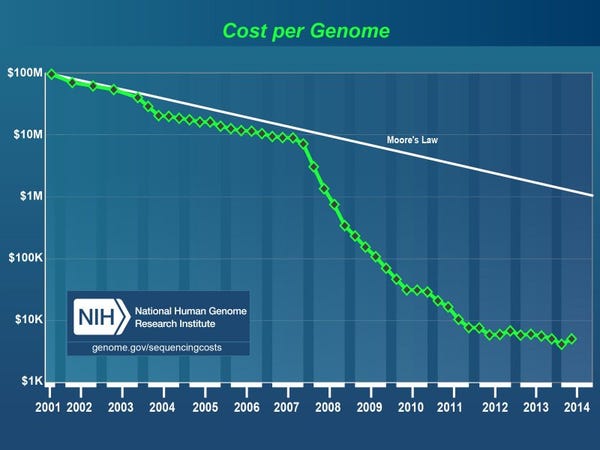

The costs associated with sequencing genomes have been decreasing quicker than

the cost benefits linked to Moore's Law for computing. Image from the NHGRI.

Kurzweil provided an example of a girl who has benefitted from several exponentially growing technologies. "She had a damaged windpipe and was not going to be able to survive so they scanned her throat with noninvasive image--the spatial imaging resolution of which has doubled every year and built her a new windpipe in a computer using CAD and printed it out with a 3-D printer using biodegradable materials," he said. "They then added to that scaffolding with the same 3-D printer modified stem cells and then grew out a new windpipe with that scaffolding. They then installed it surgically and it worked fine."

As for the field of genomics alluded to earlier, that field is evolving at a rate faster than Moore's Law. "That first genome cost $1 billion dollars. We are now to a few thousand dollars per genome," Kurzweil said. "And it is not just collecting this object code of life. Our ability to understand and model this data and to simulate and to reprogram this ancient software is also growing exponentially."

Genomic technologies are a thousand times more powerful than they were a decade ago after the Genome Project was completed and they will be another 1000 times more powerful in 10 years and a million times more powerful in 20 years.

"This is a grand transformation of medicine," Kurzweil explained. "You can, for example, today turn off the fat insulin receptor gene, which is one of these 23,000 software programs that we have inside of us." This gene essentially says: 'hold on to every calorie; this hunting season may not work out so well.' While that gene may have played an important role 10,000 years ago, today it underlies an epidemic of obesity and diabetes. "I would like to tell my fat insulin receptor gene: 'you don't need to do that anymore. I am confident that the next hunting season will be good at the supermarket.'"

In experiments, scientists have succeeded in turning off this gene in mice. The animals ate ravenously and remained slim. "They got the benefits of being slim and lived 20% longer," Kurzweil said. The Joslin Diabetes Center is working on bringing that to the human market.

He noted that he was working with a company that is adding a missing gene in patients with pulmonary hypertension and terminal disease caused by a missing gene. "So we scrape out lung cells or the throat and add a new gene. We then reinject those cells with the patient's DNA but with the gene added and this has actually cured this disease," he said.

There are many examples of the benefits of exponentially progressing technologies that are at the edge of clinical practice. "You can now fix a broken heart for example -- not from romance, that will take some more developments in virtual reality -- but from a heart attack," Kurzweil said. "My father had low ejection fraction in the 1960s. We didn't know anything about stem cells then. You can modify adult stem cells to rejuvenate the heart," he said. "You can't do that yet in the United States; you have to be a medical tourist. You can do it in Israel and some other countries. But it is right on the edge of clinical practice."

Developments like these are now trickling into clinical practice. "It will be a flood in the next decade," Kurzweil declared. Most of the projections of the future of health, wellness, and longevity are off base because they have "completely ignored this grand transformation--ignoring the fact that it is exponential and no longer linear," he said.

Learn more about cutting-edge medical devices at BIOMEDevice Boston, April 13-14, 2016. |

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to our daily e-newsletter.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)