Implantable Wireless Monitor Targets Radiation Treatment

Originally Published MDDI July 2006R&D DIGEST Maria Fontanazza

July 1, 2006

R&D DIGEST

|

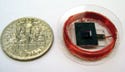

Babak Ziaie displays the wireless transponder developed at Purdue. |

Via a wireless transponder, doctors may be able to monitor the exact amount of radiation received by a tumor.

“Right now there's no way you actually know what [dosage] the tumor is receiving, unless you stick patients with a needle and put sensors inside them, with wires coming out,” says Babak Ziaie, PhD, associate professor at Purdue University's School of Electrical and Computer Engineering (West Lafayette, IN). To solve this problem, the researchers set out to develop a wireless transponder about the size of a grain of rice that could be implanted in and around a tumor using a large hypodermic needle. The device should soon include the capability to track a tumor as it shifts in the body.

The Purdue researchers are currently using a dime-sized prototype, but Ziaie anticipates that a miniaturized version will be ready by summer's end or early fall. “It has to be small enough to be able to use a hypodermic needle—you don't want to do surgery to implant these things,” says Ziaie.

About 1 cm in length and 2 mm in diameter, the wireless transponder is enclosed in a glass capsule. Because the device is so small, it can be left inside the body after radiation treatment. The main design challenge is to make the device even smaller without reducing its sensitivity. “With most radiation sensors, when you reduce the size, they get less sensitive. That's a natural law of physics, but we're getting around that with some clever tricks,” says Ziaie, who isn't revealing those methods.

|

Although the device is already very small, Ziaie's goal is to create a version that can be injected via syringe. |

The transponder's design is much simpler than other systems used during radiation therapy, according to Ziaie. The device is inexpensive to manufacture, and no assembly is required. “You can't make it simpler than this. Our device is totally passive and doesn't require any electronic components,” says Ziaie. “It's basically capacitance and inductance. Plus, when patients go to radiation therapy, they receive huge amounts of [radiation]. Electronics can be degraded by radiation, so you don't really want to put active electronics inside these devices, because you never really know what the radiation is going to do to the electronics.” Instead, electrical coils located outside the body trigger the device.

“The idea is to use electrets,” says Ziaie, speaking of electrical magnets. “Our device is a miniature ionization chamber where the charge on the electret pulls down a membrane. That's the capacitance, which is connected to an inductor.”

The radiation creates a positive-negative charge in the ionization chamber. It reduces the charge on the electret and reduces the force on the membrane to change the capacitance. The change in resonance frequency of the circuit can then be detected from outside the body.

For the next generation of the device, which could be ready in about a year, the researchers will be adding a tracking system. As a person moves, breathes, and engages in activities, a tumor, just like organs, shifts in the body. The tracking system provides the precise place of a tumor, which could help doctors dispense radiation doses more efficiently. Ziaie says it should be similar to transponders or radio-frequency identification tags that are implanted under an animal's skin for tracking.

The National Science Foundation funded the research. The engineers are performing further work on the transponder with researchers at the Indiana University School of Medicine (Indianapolis).

Copyright ©2006 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)