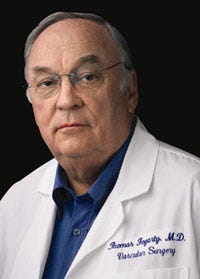

Exclusive: Noted Inventor Thomas Fogarty, MD Shares Insights on the Crux Inferior Cava Filter

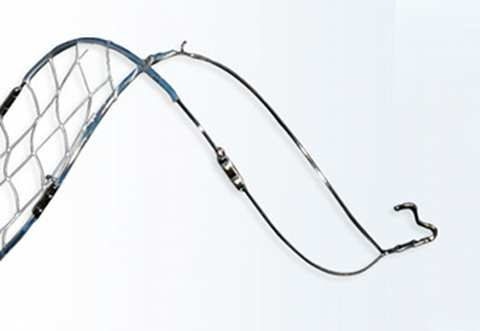

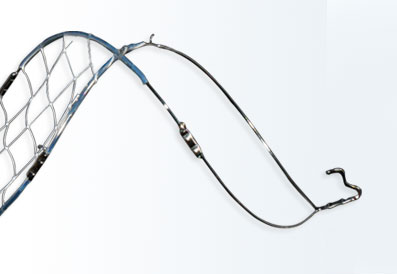

The Crux retrievable inferior vena cava filter (VCF) represents the first significant innovation in vena cava filters in 40 years. Crux Biomedical designed the device to overcome problems associated with retrievable VCFs, including tilting of the filter, device migration, fracturing, and retrieval difficulties.

March 28, 2012

The Crux retrievable inferior vena cava filter (VCF) represents the first significant innovation in vena cava filters in 40 years. Crux Biomedical designed the device to overcome problems associated with retrievable VCFs, including tilting of the filter, device migration, fracturing, and retrieval difficulties.

To address these problems, the Crux VCF features a self-centering design in the inferior vena cava to prevent filter tilt, which avoids complications that make retrieval of the device difficult. In addition, the device supports bidirectional retrieval to enable it to be removed from either a jugular or femoral approach. The device also offers tissue anchoring that provides fixation in the presence of large clot burden without perforating the wall of the inferior vena cava.

The safety of the device is supported by a recent study presented at the Society of Interventional Radiology meeting, in which the VCF achieved 98% success in filter deployment and 98% success in attempted retrieval. In the study, the average retrieval time was 7 minutes. The average filter retrieval was attempted at 83 days with a range of 6 to 190 days.

To gain some perspective on the device, MD+DI editor-at-large Brian Buntz spoke, in a one-on-one interview, with Crux founder and noted device inventor Thomas Fogarty, MD. Fogarty is a cardiovascular surgeon and a former Stanford University professor who has also been inducted into the Inventors Hall of Fame.

MD+DI: I was wondering was whether you can give me some perspective on the development of the device and how its unique design came about?

Fogarty: We had observed that available vena cava filters weren’t working as well as they should be. And that was further reinforced by an FDA alert issued in August 2010, which cautioned industry that there were some serious problems with defects with the current filters on the marketplace. That reinforced the need to do something better with regard to vena cava filters.

We started about seven years ago addressing the problems. A group of engineers, Frank Arko, MD and myself got together and essentially came up with a design that specifically addressed the existing problems point by point.

Those problems were that you often had penetration of the cava wall, which obviously led to significant complications—sometimes fatal hemorrhages because the device went into the aorta. The other complications were penetration to adjacent organs such as the small bowel and the fact that the filters tilted—in other words, they didn’t go in a straight line as they were designed to do.

The existing technology, virtually all of it, is based on a concept that was introduced about 40 years ago. Those devices are built like a tent: you have an apex and a base. And sometimes on implantation, that base would tilt and push the apex of the device into the cava wall. It would essentially grow into the cava wall. Because it tilted, the base was on an angle so emboli would get by. And when the tip grew into the cava wall, it made it virtually impossible to remove it.

The existing technology, virtually all of it, is based on a concept that was introduced about 40 years ago. Those devices are built like a tent: you have an apex and a base. And sometimes on implantation, that base would tilt and push the apex of the device into the cava wall. It would essentially grow into the cava wall. Because it tilted, the base was on an angle so emboli would get by. And when the tip grew into the cava wall, it made it virtually impossible to remove it.

Those were the problems that we identified and addressed. We did all of the bench testing, durability testing, animal testing, cadaver testing, a clinical trial, and submitted to the FDA.

MD+DI: Do you think this filter has the potential to be a revolutionary product? If so, why?

Fogarty: It is certainly going to cause a major paradigm shift. From an acceptance standpoint, when you have a new product on the market that addresses all of the problems that the prior products have, physicians recognizing that will use the newer product for many different reasons. One of them is they want to do a better job for the patients. Another compelling reason: if you use a product on the marketplace, and the FDA has made public observations about it, there is a pretty strong legal incentive to use the newer product.

MD+DI: The device has been submitted to the FDA via the 510(k) pathway. Can you help me understand why the 510(k) pathway was used for this device rather than the PMA route? What kind of product is it substantially equivalent to?

Fogarty: Well, it is substantially equivalent in terms of intended use to products currently on the market. So, FDA clearance depends on that. But the fact is that all of the other devices required clinical trials. We did a clinical trial that is larger than any other that had been done for this type of device.

MD+DI: Can you explain the importance of the bidirectional retrieval?

Fogarty: You need bidirectional retrieval and bidirectional delivery.

Let’s talk about delivery first. You can deliver this from the jugular vein in the neck or you can deliver it from the femoral vein in the leg. Sometimes, because there is a lower injury to the pelvic area, it is dangerous to access from the femoral approach or you just can’t do it because it may not be accessible. So you need access to the jugular, which is the conventional way these filters have been delivered for a long, long time.

Sometimes, you do not have access to the jugular for a variety of reasons. For instance, the patient may have a pacemaker, which often is placed through the jugular. So delivering a device through the jugular, when you have pacing leads there, can be dangerous. In that case, you want to be able to deliver that from the femoral vein.

The same is true of bidirectional retrieval: it gives you many more options than we used to have. And that provides more safety.

MD+DI: Does Crux Biomedical have plans to target conditions other than pulmonary embolism?

Fogarty: We actually are in a process of developing another application of the same technology, which is related to the distal protection during endovascular placement of aortic valves.

Now, when aortic valves are put in through a catheter system, the largest complication is stroke due to breaking off of material from the valve that you are replacing. Obviously, that is not good for the patient.

The same technology that is used in this vena cava filter has the capability of preventing this material from breaking off and going to the brain and causing strokes. So far, all we have done is the animal testing to show this, the bench testing, and cadaver testing. We are going to have to do a clinical trial and we have begun to initiate that effort.

So, there are going to be two very significant applications of this technology.

The footage below shows the deployment of the Crux inferior vena cava filter:

;

The footage below shows the retrieval of the filter:

Brian Buntz is the editor-at-large at UBM Canon's medical group. Follow him on Twitter at @brian_buntz.

You May Also Like