Wearables: Not Just a Technical Challenge, a Human One

For wearables to catch on, designers need to consider how they will affect the people who use them.

January 23, 2015

For wearables to catch on, designers need to consider how they will affect the people who use them.

By T. Grant Leffingwell

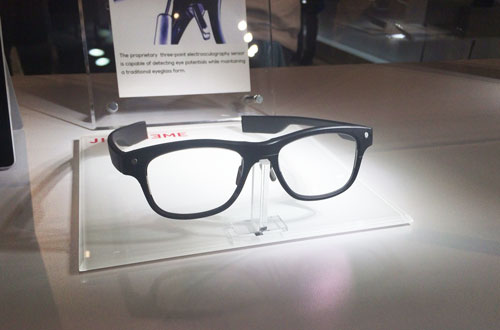

Jins Meme smart glasses were one of many wearables on display at CES.

If the 2015 CES consumer technology show is any indication, wearable computing has entered the mainstream. Wearables aren’t just for wrists anymore. The hottest buzz at CES surrounded gadgets that track us from head to toe, from things like headbands that measure brain waves to slippers that stimulate blood circulation.

Yet for all this consumer demand, the year didn’t start off well for wearables. Google announced it was ending sales of its Google Glass Explorer platform due to low consumer and developer support.

If consumers are clamoring for this technology, why are some innovative technologies failing? And are there any lessons learned for mobile health overall?

Although wearable technology (of the “smart” kind) is still in its infancy, some effective design trends have already developed.

Here are three principles that are common to successful wearable products and mHealth in general:

Use a human-centered approach to design.

Innovations that are developed using a human-centered process will be adopted; those that focus solely on technical wizardry will likely be destined for failure.

From a technological perspective, Google Glass was a success. Its creators saw a series of engineering challenges and innovated marvelous solutions for them. But while Glass developers succeeded at addressing the technological problems, they failed at addressing the human ones. They didn’t give enough attention to the human factors associated with the consumers who would be using the product, nor did they anticipate the negative social implications that the users of their tool would experience.

Make wearables as “transparent” as possible.

Assume that users expect your widget and its interface to have an understated quality to it. If possible, it should blend into and/or complement its surroundings. This is especially important for products that are intended to be worn in public.

Again, consider this another shortcoming of Google Glass, which was, quite literally, in everyone’s face. Instead, design it in such a way as to allow the user to decide whether he or she wants to draw attention to it or to wear it discreetly.

Design your device to interact with other devices.

Human brains are hard-wired to seek out patterns. Take advantage of this by making sure your device plays nice with other sensors, trackers, apps, and smartphones.

A single stream of data, out of context, won’t be that useful to someone once they get past the gee-whiz phase of new ownership. The true potential of any mHealth solution is realized when multiple streams of data are consumed in the context of each other, over a significant period of time. The empowerment a user feels when manipulating his or her own information in this way can be essential to encouraging a long-term engagement with the product.

T. Grant Leffingwell is principal research scientist at Battelle.

You May Also Like