User-Centered Design For Medical Devices: If It Isn’t Documented It Doesn’t Exist

The FDA and international standards bodies have long recognized that use error committed during interactions with medical devices negatively influences patient safety. In many cases, these errors are the result of poor design. The regulatory pressures are increasing to demonstrate that products are safe and easy to learn and use. Given the recent addition of the human factors discipline to the Office of Device Evaluation (ODE), the medical device industry is in a state of flux.

September 7, 2012

The FDA and international standards bodies have long recognized that use error committed during interactions with medical devices negatively influences patient safety. In many cases, these errors are the result of poor design. The regulatory pressures are increasing to demonstrate that products are safe and easy to learn and use. Given the recent addition of the human factors discipline to the Office of Device Evaluation (ODE), the medical device industry is in a state of flux. For some devices, a development program may just be nearing transfer to manufacturing only to be halted by new, user centered design requirements for regulatory submission, i.e., a usability validation study. This article will provide solutions for meeting newer FDA requirements for validation studies without mandating that a client start anew or lose too much development time.

|

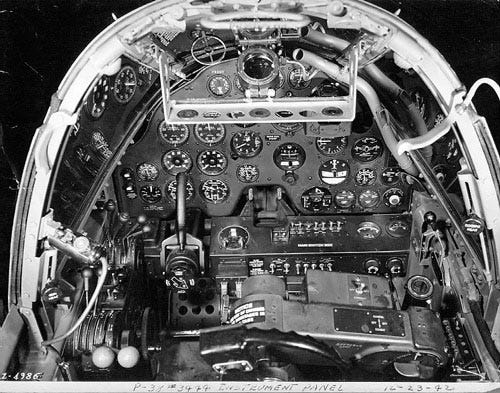

The lockheed p 38 Lightning aircraft from WWII demonstrates user-centered design. Photo used with permission from www.world-war-2-planes.com |

If user centered design activities have not been conducted during the development process, there is risk that the design is not conducive to consistently safe use. However a sound validation study is still possible if it includes the relevant users and testing scenarios to ensure the method follows FDA guidelines. Using the tools discussed here, some risk to the project can be reduced. The goal is to determine the prerequisites (e.g., user profiles, safety related functions and intended use environment) for a successful submission of a validation study.

This article will also cover good practices for meeting these requirements from the start of a program. That is, incorporating the user early and often in the design decision process. The objective is to ensure a user-centered design so that by the time you reach the validation study, all issues and concerns have been addressed. The design is sound so the risk associated with a validation study is minimized.

User Design Comes Full Circle

A high tech culture has a tendency to quickly implement technologies for the good of society and the bottom line. First to market is key; and first is defined as the latest gadget, not the latest, usable gadget. In this environment, knowing the customers (i.e., users) and how they might interact with a product takes a back seat to technology- and resource-centered factors. User-centered design is a remedy for this condition. Considering the users’ needs and abilities throughout the development cycle is the only way to ensure a product is easy to use and as safe as possible.

The popularity of user-centered design, whether it is due to safety or bottom-line concerns, has ebbed and flowed since its early days in the cockpit design of WWII aircraft. It typically lags just behind technology booms. In a way, the human factors discipline and user-centered product design have come full circle. They began as a necessary process in the design and development of safe machines as they became more and more sophisticated. Then usability research became relegated to offering a competitive edge to manufacturers of consumer products. Now, human factors are again on the front lines in ensuring use error is minimized and safety is maximized in the design of today’s high tech medical devices.

Human Factors and Regulation

Both large and small device manufacturers are being asked by ODE to provide evidence of use error analysis and user-centered design during premarket submissions. However, their respective development processes might not include sufficient human factors input. In many cases a development program may just be nearing transfer to manufacturing or introducing a new product in the U.S. market only to be halted by newly enforced, user-centered design requirements for regulatory submission.

Many device manufacturers share similar regulatory experiences. They have received a review of a premarket submission that states they need to conduct a usability validation study. Others are at the point of submission and need to fulfill the user-testing requirement but have not previously tested the product with actual users.

The only way to be completely sure a product meets the usability requirements for a successful submission is to employ a user-centered design process throughout the development cycle. However, there are strategies for reducing the risk of deficiencies by meeting many FDA guidelines and ISO requirements for usability validation studies without mandating that a client start anew or lose too much development time.

The first steps toward conducting a validation study can be found in the introduction to FDA’s Guidance document on human factors validation activities, which states that these activities must “demonstrate and provide evidence that a medical device, as designed, can be used safely and effectively by people who are representative of the intended users, under expected use conditions, for essential and critical tasks.”1

|

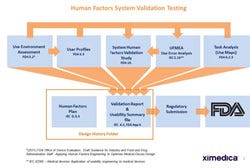

Figure 1. This diagram illustrates the prerequisite nature of various exploratory activities for conducting a usability validation study and its inclusion in the device history file (DHF) and subsequent submission. Other activity reports such as the UseFMEA should also be placed in the DHF and be part of the submission materials. |

The implications of this statement drive the necessary, preliminary activities for conducting a meaningful, thus successful, usability validation study. It implies the manufacturer must understand the intended user population, know the conditions under which the device will be used, and possess detailed knowledge of the essential and critical tasks required for the intended use of the device. Figure 1 illustrates the interdependence of each of these activities along with references to the specific sections within the guidelines and associated ISO standards.

The activities referenced in FDA’s guidelines are exploratory in nature. That is, they should be conducted early in the development cycle to drive design so that the outcome is a user-centered product. In many cases, however, once an organization realizes they are required to perform a validation study and the extent to which they need to justify the current design, they perceive themselves as unprepared. It could be that the employees don’t possess the required information or that the company has not conducted the prerequisite studies. However, in many instances, organizations do have a pretty good understanding of the users and intended work environment through early marketing activities, knowledge of predicate device usage, and contact with domain experts and key opinion leaders; they just haven’t formalized such through documentation. If they have such knowledge, the process becomes a matter of investigating and uncovering activities that can be used to show an understanding of the user, the use environment, and the tasks. An important maxim when planning to submit a usability validation study is, “If it isn’t documented, it doesn’t exist.” In essence, the organization may have conducted some human factors exploratory work, they just need to recognize it and get credit for it, so to speak.

The boxes in Figure 1 represent needed documentation for a validation study to proceed. FDA guidelines provide a road map for describing the aspects of the user population that are critical to safe use and must be considered in product design. The sample of test users to participate in the validation study must be drawn from this population. Likewise the testing environment should mimic those aspects of the real world associated with product use. If the device will be used in the home, for example, then the testing environment should mimic that setting. The researchers must understand and copy idiosyncrasies in the validation test setting, such as low light levels that are common to homes. In addition, the organization needs to understand and document the intended use of the device from a task perspective. This step is accomplished by performing a task analysis. A task analysis helps gain an understanding of the necessary tasks and the skills needed to complete each. It allows the design team to understand the types of errors that may occur during actual use. The task analysis becomes the framework for designing the validation testing protocol. It includes all essential and critical task steps that may be required of the end user during normal and remedial operation. In addition, the task analysis is the framework used for building a use failure mode and effects analysis (UseFMEA). This activity identifies and assesses the risk of potential use errors. The potential errors that carry significant risk need to be documented and included in the usability validation study.

Finding out late in the development process that a usability validation study is required for a premarket submission may be daunting. However, with a little research and careful adherence to guidelines and standards, the need for costly or lengthy activities may be reduced.

|

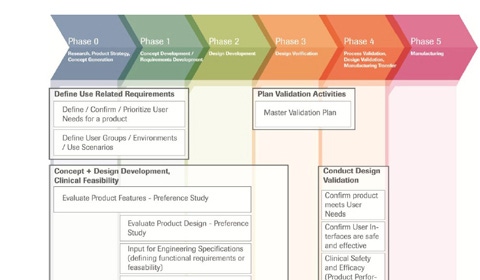

Figure 2. Typical user-centered development cycles involve the end user early and often. |

Integrate Human Factors Activities into Development

Conducting the first usability test at the end of the project for validation purposes and after design freeze carries considerable risk. It may be that, even after the best efforts of the design team, the validation study reveals that the product design lends itself to use error that, if it occurred in the real world, could result in risk to the patient or clinician. In this case, the only option may be to revisit the device design and make needed changes through design control processes. Such efforts can be quite costly to the overall project. In addition, usability testing would need to be conducted again to ensure all mitigations were effective and no residual risk was generated. In essence, an additional validation study would be required.

A much less risky (and cost effective) endeavor is to incorporate human factors activities into the development process. This user-centered design process allows the team to determine risk due to use error very early in the project and design it out before the changes become expensive. That is, human factors input can help define design requirements, not just validate them at the end. Figure 2 depicts a typical user-centered development process.

Note that, per Figure 2, the end user is taken into account and, indeed, allowed to participate on a consistent basis throughout the entire process. By the time a usability validation study is conducted, the organization knows most foreseeable risk associated with use error has been accounted for and eliminated via design controls. The usability validation study has the potential of being simply a technicality at that point—in contrast to the unknowns that may be present if the validation study is the first contact with real users, in an actual use environment with simulated clinical tasks.

Conclusion

Finding out through the regulatory premarket review process that a usability validation study is required may not be as daunting as first perceived. An understanding of study prerequisites and how to find them is key to designing a sound usability validation study protocol and, ultimately, meeting the needs of the FDA reviewers. However, this process still holds a certain amount of unknowns. To ensure these unknowns are minimized, thus reduce risk to the project, a user-centered development process should be incorporated.

References

Medical Device Use-Safety: Incorporating Human Factors Engineering into Risk Management, July 18, 2000, FDA; Available from Internet: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm094460.htm

+++++++++++++

Dean Hooper is human factors engineer at Ximedica. He has provided human factors input to software and hardware development projects for more than 17 years. Before joining Ximedica, Hooper designed the user interfaces for a system that treats cardiac arrhythmias via remotely controlled sensing, mapping, and ablation catheters. Hooper has been awarded design patents and produced several publications. He presents at conferences, including AdvaMed seminars on initiating a human factors programs and robotic system development case studies. He also has received an innovation award for his work in system design of implantable pacemakers. Hooper holds an MS in cognitive science from New Mexico State University.

More on User-Centered Design

| Achieving Success at User Interface ValidationLessons manufacturers can apply to increase the chance of a successful validation usability test. |

| User-Centered Design and the Medical Device Start-UpStart-ups may have an advantage within the medical device industry because of their innovative ideas. The trick is to use those ideas effectively through user-driven design. |

| Creative Collaboration: User-Centered Design in PracticeA case study of the development of a blood parameter monitor illustrates the benefits of teamwork and human factors engineering during the design process. |

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)