How to Avoid Making a Medical Device Flop

February 5, 2015

Developing a game-changing product can be incredibly tough, even if you have a brilliant team and tons of cash. Just ask Google.

Qmed Staff

In the past several years, the Mountain View, CA-based tech giant has introduced Google Health, Google Glass, Google Buzz, Google Wave, Google Plus, and scores of other products that failed to make good on the initial hype that accompanied their release. And several of those projects, including Google Health, have been shuttered for good.

Innovating in the medical device space has its own challenges, of course, considering how medtech product developers must deal with regulatory affairs and a shifting healthcare landscape. On top of that though, medical device designers often must develop products that respond to the needs of not just one user, but those of a range of parties including patients, doctors, and payers.

|

Craig Scherer is a senior partner and cofounder of Insight Product Development. |

Ethnography can help device designers develop products that respond well to its use environment, says Craig Scherer, a senior partner and co-founder of Insight Product Development (Chicago). Even if you regularly use ethnographic research in your product development cycles or work with a design firm that does it for you, it is a subject worth knowing more about.

In this Q&A, Scherer delves into ethnography (and defines the term), and tackles subjects such as understanding core user needs, brainstorming, and translating promising product ideas into specs. (Incidentally, Scherer will participate in a panel discussion related to developing remote patient monitoring products at MD&M West on February 10. Insight Product Development will be exhibiting at booth #2185.)

Qmed: What is ethnography, and why does it matter to medical device companies?

Scherer: In the classic sense, ethnography means to observe cultures and the ways that people interact with each other in their "natural environment". At Insight, we often call this contextual inquiry, meaning to do research in the context of a product's use environment. This is so critically important to device companies because it is the only way to really understand the dynamic interrelationship between stakeholders (both primary and ancillary users), their environments and the products they interact with. Tools like focus groups, customer service feedback forums, and expert product reviews are great, but we believe we can only uncover real unmet needs and drive meaningful innovation by observing how users behave in context.

Qmed: How do you translate ethnography research into product ideas?

Scherer: When we are in the field doing this research, we are able to directly observe users in their environments interacting with all sorts of devices. The first takeaway is being able to map out a detailed workflow of the product's use cycle, from set-up, to use, to tear down. The second is to observe at each of the steps along the workflow where the users feel challenged or unsupported by their products and environments. We will then address these less than ideal interactions as opportunities to develop products, configurations and feature sets. Each idea can be evaluated against a wide variety of criteria, such as whether or not it supports the workflow, if there is available technology to achieve the functionality, and what cost and complexity this feature may add to the overall system.

|

For surgical device projects, ethnography means studying clinicians' workflow in the operating room. Image courtesy of Insight. |

Qmed: What kind of volume of product ideas should you generally shoot for once you have a solid sense of what the core needs are?

Scherer: The number of possible solution sets that meet the overall goals of a problem statement is nearly impossible to define at the onset of a program. Until you do that ethnographic research and have analyzed the observed problems, you have no way of knowing the possible number of permutations. You should never fill out your proposed directions with less than optimal solutions just because you don't feel like you have enough options. Conversely, you should never terminate exploration on other promising ideas just because you have more than your initial target number. Keep moving all of the good ideas forward and enlist the help of your users to help you downselect by conducting directional testing throughout the development cycle.

Qmed: Do you advocate a brainstorming-like approach where you go for a large quantity of ideas and then whittle them down later?

Scherer: Absolutely. In the previous example, we will often generate challenge statements for those areas where we observed user frustrations, and use them to organize and drive brainstorming sessions. Another important thing to consider is that these sessions are greatly enhanced by tapping into a wide variety of internal stakeholders to provide varying perspectives. Representatives from engineering, manufacturing, regulatory, marketing, as well as clinical experts should be involved in this process, especially when it comes time to downselect. One caution is that brainstorming is not the end-all to your product solution needs. Think of it as providing a jumpstart to your design development and providing alignment between all of your internal stakeholders.

|

|

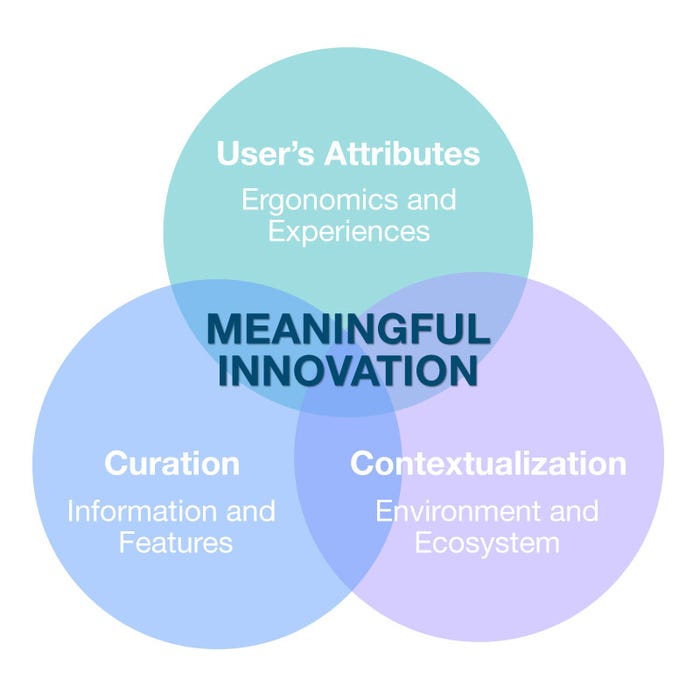

Meaningful innovation requires an understanding of the user's attributes, curation, and contextualization, Scherer says. Image courtesy of Insight. |

|

Qmed: What advice would you have for a normal medical device design engineer regarding ethnography research and needs finding?

Scherer: In device development, it is critically important to understand our target users. What are their physical and cognitive limitations? What training do they typically have or require? What is their state of mind, and are they overburdened with many tasks? It is equally important to contextualize their user experiences in the target environments. Is their mobility limited by space constraints? What other devices and fixtures are they interacting with? Is there ample lighting? And finally, curate the volume and organization of information and features. Don't overload them with information and features they don't need. Instead, organize them into logical formats and interaction schemes.

Qmed: It seems incredibly difficult to design a device that aligns incentives for the key stakeholders in the health care food chain. What advice would you have there?

Scherer: It is always difficult to anticipate all the needs of the key stakeholders, especially when evaluating the needs of primary users and comparing them to the drivers of critical stakeholders such as purchasing, biomed technicians, and materials management, to name a few. It's important to navigate what might seem like conflicting goals, to ensure that whatever is developed will resonate across all stakeholders.

Qmed: How good of a job do you think the medical device industry does with the needs characterization stage of product development? Why?

Scherer: The medical industry has greatly improved in the past five to 10 years. The FDA's adopted HE75 guidance has required that device companies characterize user needs as they relate to safety and clinical efficacy. This has helped these companies understand the importance of not only final usability testing, but also of the formative inputs throughout the process. These inputs are more valuable when performed in context. Most companies now realize that meaningful innovation usually comes from incorporating ethnographic research into the design process.

Qmed: Once you have identified a promising product idea, what advice do you have for translating it into specs and ultimately a finished prototype?

Scherer: Three things.

Keep the design, user experience and human factors folks involved throughout the detailed design phases. Let them advocate for the users throughout the engineering cycle. Requirements can be fulfilled in many ways before they are ultimately locked into specifications.

Iteratively test concepts with users. Don't begin and end your research with ethnographic discovery. Do multiple rounds of user testing (in context if possible) to ensure that refinements are on track and relevant.

Prototype continuously. Use today's great tools like digital simulation tools and physical 3-D printing to continue to evaluate concepts at every stage.

Learn more about user-centered design in Craig Scherer workshop dedicated to the topic at MD&M Philadelphia, October 7-8, 2015. |

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to our daily e-newsletter.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like