Four Trends from the 2012 Medical Design Excellence Awards

Many of this year's MDEA finalists fine-tuned medical device concepts to address the challenges of today’s healthcare market.

March 30, 2012

Shortly after his death this past October, Steve Jobs was memorialized in The New Yorker magazine in a story provocatively titled, “The Tweaker.” The piece, written by author and journalist Malcolm Gladwell, hailed the visionary Apple CEO’s “real genius,” which Gladwell argued was not Jobs’s ability to invent new things but rather his knack for refining existing technologies. The iPhone, for example, wasn’t the first mobile phone; it was a better mobile phone. This year’s Medical Design Excellence Awards finalists seemed to follow his lead.

“It was really striking how there were very few really new things,” jury chairman Stephen B. Wilcox says of the submissions. “We didn’t really see any completely new technology, and by that I mean something to either address a condition that wasn’t addressed before or something that clinically was really unique.”

Instead, many of the devices entered into the competition were improved iterations of products and technologies that have been around for some time.

“People are inventing things to try and make healthcare more efficient and do more with what we have,” says juror Edward G. Chekan, MD. “We didn’t see a lot of new platforms or new developments. What we did see were people saying, ‘Let’s take what we have and make it better, lower the cost, or make it more efficient.’”

From an easier-to-use inhaler to smaller, cheaper, and more efficient versions of an x-ray machine, a ventilator, and a prosthetic foot, the 2012 finalist products included features to make existing medical device concepts better.

Designed for Affordability

In many ways, this year’s MDEA submissions reflected the realities that have confronted the healthcare industry over the past few years—from the Great Recession to healthcare reform. Because of medical device firms’ lengthy product development cycles, the effects of the recent past are just now making their way to the market.

“I think that we’re seeing the results of decisions that were made at the beginning of ’09, when the economy was tanking,” says Wilcox, principal at product development consultancy Design Science (Philadelphia). “It takes about three years to develop a product, so we’re seeing projects that were launched in late ’08 and early ’09, when the economy was at its depth and when everybody was interested in saving money.”

Many of this year’s finalists were relatively low-priced devices or technologies that cut costs for end users as opposed to products intended to dramatically improve therapy.

|

The DermScope enables an iPhone to capture dermatoscopic images. |

One such device is the DermScope, a device that enables viewing and capture of dermatoscopic images using an iPhone. Manufactured by Canfield Scientific Inc. (Fairfield, NJ), the device consists of a machined-aluminum lens attached to a clamshell housing, which holds the phone. It also features a circuit board, mini USB input port, and a lithium-ion battery. Users of the DermScope can capture images of skin lesions or other conditions, zoom to 30× magnification, tag the images, and transmit them to remote locations.

At $895 for the device and $4.95 for the accompanying app, the jurors noted during judging that the DermScope could potentially replace equipment that costs thousands of dollars. That could open the door to its use by family physicians, who could send shots of suspicious skin spots to dermatologists for closer inspection.

Another device that aims to help cut healthcare costs is the CT-Guide Needle Guidance System. Made by ActiViews Inc. (Wakefield, MA), the surgical navigation system is designed to aid in procedures such as biopsies, marker placement, and soft-tissue ablation in cancer care.

Surgical navigation devices, of course, are nothing new. In fact, ActiViews president Christopher von Jako worked on one of the first such systems to hit the market back in 1993. But the CT-Guide improves upon models currently on the market, which are bigger, more expensive, and more complex.

|

The CT-Guide Needle Guidance System is smaller, simpler, and less expensive than other surgical navigation devices. |

The CT-Guide consists of just a single-use miniature video camera, a sterile adhesive sticker with color-coded guides on one side and imaging reference markers on the other, and a computer workstation loaded with the company’s proprietary navigation software. At $80,000, it’s around half the price of similar navigation systems on the market.

“The beauty in CT-Guide navigation is its simplicity, which is real progress," von Jako says. “We don’t need the extra components that other navigation systems need in order to operate.”

CT-Guide navigation could also potentially improve the accuracy of the lung interventions for which it has received 510(k) clearance. Currently, most physicians perform such procedures freehand, a method whereby they insert the needle into the body and use CT scans to ensure it’s in the right place. That takes time and exposes the patient, and sometimes the doctor, to additional radiation. The more time the needle spends inside the lung might also increase the chance of complications such as collapsed lung, von Jako says.

Easing the Burden of Chronic Disease

Among the challenges looming large for healthcare providers are chronic diseases, such as diabetes, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Nearly one in two Americans suffer from at least one chronic disease, and such conditions account for 70% of all American deaths each year, according to the CDC. Chronic disease is also the leading cause of mortality worldwide, according to the WHO.

For patients who suffer from chronic diseases managing their conditions becomes in some cases an everyday task. Many of this year’s MDEA finalists sought to lessen their burden.

“They weren’t curing the disease, they were facilitating the lives of patients with chronic disease,” says Chekan, who is director of medical education at device manufacturer Ethicon Endo-Surgery (Cincinnati).

|

The Combitide Starhaler seeks to improve upon standard-of-care asthma and COPD inhalers. |

The Combitide Starhaler is a drug-delivery device for patients with asthma or COPD. It was designed by Cambridge Consultants (Cambridge, UK) for Sun Pharmaceutical Industries (Mumbai) with the intention of improving upon standard-of-care inhalers, which present problems for users who have compromised lung function.

“People just can’t do it or don’t now how to do it, so they don’t get the full therapeutic benefit,” says Duncan Bishop, Cambridge Consultants program director.

The device is made up of a primary drug container, which holds the drug dose; a breath actuation mechanism; a piercing mechanism to open the sealed drug container; an airway/deaglommeration engine, a case and mouthpiece; and a cap and indexer. It delivers a steroid and beta agonist combination deep into the user’s lungs.

In designing the Starhaler, the team faced three challenges: It had to ensure delivery of the drug in the deep lung, overcome the user’s low lung power, and make the device easy to operate. To address the first, the drug particles had to be separated from a lactose carrier, enabling them to be inhaled into the lung while the larger lactose particles are confined to the back of the throat. It was also important to ensure as much of the drug as possible was emptied from the device and made its way into the patient. To accomplish that, Cambridge Consultants developed a punch-and-retreat piercing mechanism to open and clear the airway. To deagglomerate the drug, the team designed an airway that harnesses impact, shear, and centrifugal forces to separate the drug from the carrier. The breath actuation mechanism only dispenses a dose if the full inspiratory flow required to inhale a therapeutic dose is achieved.

“We made it pretty foolproof,” Bishop says. “If device works for you, you’ve got a therapeutic dose.”

Cambridge Consultants also incorporated a few human factors features into the Starhaler’s design. The device is small enough to slip into a pocket, includes a tactile dose counter that can be used by the visually impaired, and glows in the dark, so users can find it even with the lights out.

Products for Emerging Markets

|

The NOMAD Pro Handheld X-ray System could help improve dental care in underdeveloped countries. |

Traditional markets for medical devices such as the United States, Europe, and Japan are starting to mature, while growing populations and rising middle classes in developing nations are resulting in greater demand for healthcare products in other parts of the world. That presents an opportunity for medical device makers.

“It’s tempting for these companies to say, ‘Gee, if we could get a little bit of this nontraditional market, the volume could be significant,’” Wilcox says.

Reflecting that trend, some of this year's MDEA finalists were devices retooled for use in underdeveloped countries.

One such device is the NOMAD Pro Handheld X-ray System, made by Aribex (Orem, UT). At just 5.5 lb and 6.25 × 10.75 × 10 in., this cordless, handheld x-ray device for intraoral dental use can be used outside of a traditional dental office, opening it up for use in humanitarian or other remote applications, according to the company.

“This could really make a difference in terms of dental care in underserved areas,” says juror Jay Goldberg, who directs the healthcare technologies management program at Marquette University and the Medical College of Wisconsin.

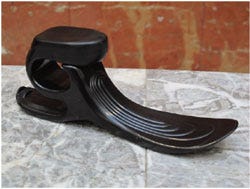

Another product aimed at improving the lives of people in developing countries is the Niagara Foot, a prosthetic foot that “anatomically mimics biological foot action by absorbing and releasing energy in a controlled way,” according to its manufacturer, Niagara Prosthetics and Orthotics International (Fonthill, ON, Canada).

President Rob Gabourie says he designed the product specifically as a low-cost option for people in underdeveloped areas, especially places like Cambodia, where there is a high rate of limb loss from land mines.

|

The Niagara Foot is a cost-effective prosthetic option that could help people in developing countries who have lost a foot. |

“There were no high-performance devices available for underdeveloped areas, period,” he says. “The one criticism I’ve heard over and over again is that they don’t stand up well to the environment, and the ones that do manage to stand up well, there’s really no energy return with these feet.”

The company field tested the product in Thailand and El Salvador, where conditions can be trying for prosthetics. Through the tests Gabourie, a certified prosthetist and orthotist, gained a deeper understanding of the unique needs of his target markets. Ease of use was the most important factor, so he designed the Niagara Foot to be field adjustable. It had to be durable and waterproof, but cosmetics were also important to users, so he gave the device a removable cosmetic sheath.

Of course, to be a viable option for consumers in developing economies, all of this had to come at a low cost. To keep the price down, Gabourie used injection molding to create the prosthetic from DuPont’s Hytrel thermoplastic polyester elastomer. Thanks to the manufacturing technique, the donation of materials and expertise from many people who worked on the project, and the fact that Gabourie says he never intended the device to make a profit, the cost of the device is just $100 plus shipping.

Bringing Devices Down to Size

Bigger isn’t always better, as some of this year’s MDEA finalists proved. Shrinking existing technologies can yield benefits for both patients and physicians.

The Non-Invasive Open Ventilation (NIOV) System, from Breathe Technologies Inc. (Irvine, CA) is designed to facilitate ambulation for patients with respiratory insufficiency, such as COPD patients in the later stages of the disease.

|

At 1 lb, the NIOV Ventilation System is significantly lighter than most other ventilators. |

“Patients go into a sedentary state of just sitting in their house,” says Joe Cipollone, vice president of R&D for Breathe Technologies. “It takes their breath away to walk, so they don’t go out and get their mail. They have trouble with vacuuming. A lot of them don’t wash dishes.”

Oxygen therapy increases the amount of oxygen in their lungs, but it doesn’t help them take deeper breaths. Ventilators combined with oxygen can do both, but at 20 lb and accompanied by large-bore 22-mm ID tubing, they’re heavy and cumbersome.

“The only practical way to use existing ventilators is if the patient is in a wheelchair,” Cipollone says.

Breathe Technologies knew to improve patients’ lives it had to reduce the size of the ventilation system, but in doing so it had to break the paradigm of 22-mm ID tubing associated with current ventilators.

To reduce the size of the tubing for the NIOV, the company developed an open ventilation system that differs from other ventilators, which deliver all of the patient’s breathing gases from the machine through the tubing. The NIOV delivers only a portion of the breathing gases through the tubing from the ventilator. The rest comes from harnessing the Venturi effect, which entrains ambient gases through a proprietary nasal pillows interface to make up the total breathing gas required by the patient. This enabled the use of 3-mm ID tubing.

Breathe Technologies also recognized that target users for the NIOV have access to 50 PSIG oxygen. It used that as a source, eliminating the need for a blower and its associated battery power. Additionally, the company eliminated the tubing inside the ventilator, replacing it with a structural pneumatic manifold. In all, the NIOV weighs just 1 lb.

The LS-1 is another product that cuts down the footprint of device technology. This portable intensive care unit combines a physiological monitor, ventilator, infusion pumps, and fluid warmer in one platform.

|

The LS-1 "suitcase" ICU is a new iteration of the LSTAT, a similar product in a stretcher platform that was an MDEA winner in 2001. |

“If you go into an emergency department or ICU or any healthcare environment where you’ve got a lot of critical care patients, you’ll find a clutter of individual devices, with separate displays, conflicting alarms, and spaghetti of cables,” says Matthew Hanson, vice president of Integrated Medical Systems Inc. (Signal Hill, CA), the product’s manufacturer. “What’s grown up around the caregivers is just an unmanageable amount of equipment clutter and information overload.”

Integrated Medical Systems includes among its primary shareholders Northrop Grumman Corp., which develops systems for use in aerospace, defense, and other industries. The team that developed the LS-1 was familiar with miniaturization and integration from its work on the cockpit of the B-2 stealth bomber. The device components of the LS-1 are actually off-the-shelf devices and data systems. The innovation came in integrating all of the systems onto a common data bus and common power bus and packaging everything into a common structure.

“The architecture is the secret sauce that ultimately provides greater safety and efficiency for both caregiver and patient,” Hanson says.

The LS-1 also incorporates telemedicine capabilities, so care providers can monitor patients and controll the system from remote locations—a feature Chekan, a clinician, found especially exciting.

“As a physician, I can monitor my patients live via telemetry…and keep track of multiple patients with this device,” he says. “It’s nice to have real-time data as I’m measuring complex intensive care patients.”

The LS-1 is actually a new iteration of an MDEA winning product from 2001, the Life Support for Trauma and Transport (LSTAT), which combined a defibrillator, ventilator, suction unit, fluid-and-drug infusion pump, blood-chemistry analyzer, and patient monitor into a stretcher platform.

The lesson: It pays to keep tweaking.

Jamie Hartford is the associate editor of MD+DI and MED. Follow her on Twitter @readMED.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)