Designing a $93M Medical Technology: A Behind the Scenes Look

October 27, 2015

The design firm Nottingham Spirk provides the inside scoop on how a sleek advanced cardiac mapping technology was developed starting from a crude prototype.

Qmed Staff

|

The ECVUE vest can conform to a range of patient body types. |

In 2006, the startup CardioInsight (Cleveland, OH) was born with hopes of commercializing a new technology known as electrocardiographic imaging that had better resolution than traditional 12-lead ECG technology. The firm had secured considerable funding, which it planned on using, in part, to create an advanced prototype, using a crude Frankenstein prototype as a starting point.

In the following Q&A, three of the lead designers at design firm Nottingham Spirk, Jeff Taggart, Jason Ertel, and Jason Tilk, who worked on the project explain how they took a rough but promising technology and helped sculpt it into an advanced prototype that ultimately helped convince Medtronic that the startup was worth $93 million. (Medtronic announced the acquisition in July 2015.) Taggart is the firm's engineering program director while Tilk is its product design specialist and was Nottingham Spirk's lead industrial designer on the CardioInsight program:

Qmed: What is the background on the project? Specifically, the early stages of the technology?

Jeff Taggart: The CardioInsight creators had come to them with the base technology and had proved it out with a crude, reusable, research prototype. NS had to quickly get up to speed on this unique technology while understanding the application in the hospitals.

In addition to engineering an effective application of the technology, we had to work tightly with the manufacturing partners who were willing to try something new. We provided them support and helped them incorporate and combine new technologies and manufacturing methods and techniques to achieve the desired result.

Jason Tilk: Nottingham Spirk was able to add additional IP to the existing innovation developed by the CardioInsight team. Many hours were spent in hospitals observing nurses and technicians. The work space is often limited and the patient body types exhibited a much wider range than expected.

Early prototypes revealed much operational inefficiency. For instance, the typical industry hydrogel was too sticky and caused patient discomfort. We found a "miracle" adhesive that allowed the vest to adhere to the patient quickly and effectively while being sweat resistant.

One major design achievement was redesigning the vest panels so that all 252 sensors remained connected to the skin as the patient wore the vest. The original base material of the vest wasn't flexible enough to fit around patient. The "Aha!" moment was creating an S-curve pattern around each sensor that would allow it to wrap around a patient's body and specific curvature, as well as allowing a little bit of stretch for fit.

Qmed: What were the specific challenges involved in the design of this device?

|

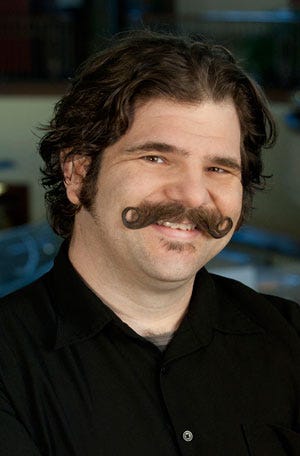

Jason Ertel |

Tilk: One of the challenges was determining how to design a vest that would wrap and fit a variety of body types while maintaining proper sensor connectivity. Each panel of the vest has 63 sensors that all ran to one common connector or plug. This connector had to be small for comfort and wearability, but robust enough to plug into the mapping system. Jeff invented new break walls to prevent arcing between the walls of the connectors, which enabled them to be small and light.

Additionally, the vest is worn by the patient for up to eight hours, so comfort, weight, and durability were also important. The fabric had to be comfortable and breathable. The construction had to be durable enough for the patient to be transferred throughout the hospital and the vest had to survive the use of an external defibrillator, while being invisible on the fluoroscope.

Taggart: An additional challenge is that the vest needed to be applied to the patient within 20 minutes, but NS was able to get the application time down to less than 10 minutes.

Ertel: When we were designing it, we were working directly with a flex circuit manufacturer getting the drawings ready. The electrodes have diagonal shapes with little dots in the middle. We wanted to make sure the manufacturer could do it up front instead of designing the device first. Just like any design transfer process, you start early with your manufacturing folks to understand what you can accomplish as oppose to doing all of your engineering and throwing it over a wall, which is unfortunately what a lot of companies do.

Qmed: What was the collaboration like between Nottingham Spirk and CardioInsight?

Taggart: The collaboration between the two companies was incredibly tight and continuous. The teams remained in frequent contact with each other when issues and breakthroughs arose. The NS/CardioInsight team was small, intimate, and focused on bringing this technology to market. CardioInsight also has a great relationship with the hospital, which enabled the team to work closely with the nurses and technicians to identify and understand the user needs for the vest.

Tilk: The collaboration was very organic and streamlined. CardioInsight was located down the hill from Nottingham Spirk, which enabled frequent face-to-face meetings. The NS/CardioInsight team would conduct weekly phone calls with vendors and manufactures, and after the calls the team would often sit in [CardioInsight founder and chief scientific officer) Charu Ramanathan's office and brainstorm questions that may have arisen during the call. Jason fondly reflected on the teams brainstorm sessions regarding segmentation and how to identify navigation points to help the computer understand the jumble of dots it received from the initial imaging.

Qmed: How long did the project take?

Taggart: It took about four months to present the first pre-production article, and another year of ongoing work to perfect the sizing and refine the manufacturing and shelf stability. We worked collaboratively with vendors and manufacturers to modify their processes to complete the vest, which often exceeded the scope of the original program.

|

Jason Tilk |

Tilk: We delivered the final working design for the small vest about a year after the original prototype was shown to NS. I estimated that the entire program was about 1.5 years.

Qmed: What were your first thoughts when you saw the "Frankenstein" prototype?

Taggart: I thought, "that's a mess! But, being from the technical field, I understood what the prototype was all about and that it did exactly what it needed to do, it just need to be taken to the next level." It was interesting to see the stepping stones they took to get all the way across the river.

Tilk: I thought, "Wow, that's crazy! I was in awe of the down and dirty nature of the prototype."

Qmed: Other thoughts?

Taggart: It was one of my favorite projects. It was an accomplishment to work on the product, but in the end it was such a great device to help people.

Tilk: I was excited and proud to be a part of this program. I can say that I have worked on something that has made many people's lives easier--doctors, nurses, and patients. It makes me happy to do what I do.

Learn more about cutting-edge medical devices at MD&M Minneapolis, November 4-5 in Minneapolis. |

Brian Buntz is the editor-in-chief of Qmed. Follow him on Twitter at @brian_buntz.

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to our daily e-newsletter.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like