A Better Approach to Developing Instructions for Use

A new process for creating instructions for use for medical devices cuts down on the time-consuming and costly steps of the cycle by asking end users for more input.

November 18, 2016

A new process for creating instructions for use for medical devices cuts down on the time-consuming and costly steps of the cycle by asking end users for more input.

Annie Diorio-Blum

The common approach to designing and developing an Instructions For Use (IFU) has been largely unchanged for years: once a product is designed and made ready for manufacturing, an IFU is then written and tested. When errors are found, changes are made, and the cycle repeats until there is an acceptable IFU version that most users will be able to comprehend. Clearly, this approach is often time consuming and costly.

Even with the more recent fundamental shift in how medical devices and products are designed--with most manufacturers moving towards a "user centered design" approach--IFU, Quick Reference Guides (QRGs), training, and labeling are typically left out of this process. Compounding the problem with patient comprehension of ancillary materials is the overuse of outdated standards found so frequently in IFUs, QRGs, and labeling.

Hear a Battelle expert discuss "Proving the Case for Your Connected Health Device" at BIOMEDevice San Jose, December 7-8. |

To address this ever-present issue, we developed an innovative process in our research in which we asked end users to "create" their own IFU by giving them the opportunity to select the words and images that best communicated the intended use of a given medical device. These insights allowed for the development of simplified instructions that were not only easier to understand, but also more likely to be used (and used correctly) and more likely to improve patient adherence. Using this approach also proved to reduce the number of formative tests needed to reach acceptable comprehension and it streamlined the human factors testing.

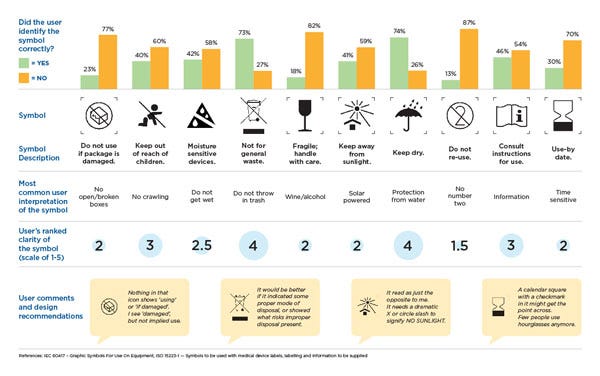

From surveys to focus groups and in-depth interviews with target users, this process can be implemented in various ways. Using a mix of quantitative and qualitative survey methods, we conducted a small study looking at how different users understand and comprehend symbols commonly found in medical devices for home use. The purpose of this study was to demonstrate how symbols that are routinely found in medical device IFUs and labeling are not universally understood. Users were provided with an image of a symbol and asked to describe what it meant in their own words. They also were asked to rank the clarity of the symbol on a scale from 1-5 (after they were presented with the correct definition).

As the results in the graphic below indicated, many of the "abstract" symbols ranked low in clarity and were not identified correctly by the participants and most commented that they would need the accompanying text to help correctly identify the symbol. In fact, some participants mentioned that certain symbol designs led them to believe they should do the exact opposite of what the symbol was trying to convey.

For example, "Keep away from sunlight" was often interpreted as "place in sunlight" or "place in well-lit area" which users pointed out is the exact opposite of the symbol intent and could have serious implications. As medical device design continues to evolve, our hope is that more manufacturers will use this approach early and often when creating IFUs and labeling.

Annie Diorio-Blum is a principal industrial designer at Battelle.

[Image courtesy of MASTER ISOLATED IMAGES/FREEDIGITALPHOTOS.NET]

You May Also Like