Behind the Design of an Automated Artificial Urinary Sphincter Implant

The CEO of UroMems shares the design and engineering story of the company's automated artificial urinary sphincter device.

August 3, 2023

A woman in France has become the first female to receive an automated artificial sphincter device for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI).

Grenoble, France-based UroMems developed the UroActive smart, automated artificial urinary sphincter as a long overdue solution for people suffering from SUI.

"It's magic," said the patient, whose name was not released. "I am so glad I can again do simple things in my daily life I was not able to do any more."

UroActive is powered by a MyoElectroMechanical System that is placed around the urethral duct and is adjustable based on the patient’s activity. It is based on a unique bionic platform using embedded smart, digital, and robotic systems which, based on data collected from a patient, create a treatment algorithm that is specific for each patient's needs.

SUI occurs when the pressure in the bladder exceeds that of the muscle (the sphincter) around the urethra, caused by activities involving high intra-abdominal pressure, like coughing, laughing, and exercising. SUI is more prevalent in women but can occur in men too.

The first-in-female robotic-assisted procedure to implant the device was completed at La Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital (AP-HP, Sorbonne University, Paris, France). The National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products (ANSM) approved the procedure. Results of this clinical study will contribute to the design and implementation of UroMems’ pivotal clinical trial in Europe and the U.S.

While this was the first-in-female UroActive implant, UroMems announced the first-in-human (male) UroActive implant last November.

Challenge accepted: The genesis for the UroActive automated artificial sphincter

The genesis for the UroActive artificial urinary sphincter came from a conversation between a biomedical engineer, Hamid Lamraoui, and Pierre Mozer, MD, a urologist, when they had the opportunity to meet about 15 years ago.

"He was saying, 'I can see my patients living a nightmare with this condition where they are suffering in silence'," Lamraoui told MD+DI.

Mozer went on to tell Lamraoui about the limitations of current treatment options for severe SUI. While mild SUI can be addressed with pelvic floor physical therapy and bulking agents, moderate and severe SUI historically have only had two options: mesh sling (which has been plagued by safety problems over the years) or a manually-operated artificial sphincter.

The latter option is an antiquated device designed in the 1970s and the last iteration of the manual artificial sphincter was about 40 years ago, Lamraoui said.

Together with Stéphane Lavallée, Mozer and Lamraoui founded UroMems in 2011 to take on the challenge of designing a new device that would overcome the limitations of current solutions by optimizing safety and performance, patient experience, and surgeon convenience. Mozer serves as the company's chief medical officer and Lamraoui is the CEO.

UroMems house rule: Constraints are for the engineers

To help inform the design of the device, the UroMems team studied the existing device, namely the mechanical artificial sphincter, to learn what surgeons and patients liked about the device and what they found lacking.

The predicate device is a hydraulic device that consists of three parts: a cuff that wraps around the urethra to control the flow of urine; a balloon, which is placed under the abdominal muscles and holds the same fluid as the cuff (this is where the fluid is moved to when the cuff is open or deflated); and a pump, which relaxes the cuff by moving the fluid from the cuff to the balloon. The pump is placed in a man's scrotum or within the major labia in a woman. Artificial sphincter users must squeeze the pump through the skin to urinate.

Lamraoui said the company has a house rule that all the constraints are for the engineers – the device must be simple for the patients.

"It's a rule that we have in house, and we will never give up on this," he told MD+DI.

So, it didn't take the UroMems team long to determine that the new device should not require patients to manually open the cuff by squeezing the pump through the skin.

"The issue with the balloon is the fact that it does not always generate the adequate pressure," he said.

But the physician selects how much pressure the balloon will generate during the procedure, and Lamraoui said there's no real rationale behind how much pressure the physician selects. If the pressure is too low, the patients will still have leaks, he said. But if the pressure is too high, the patient will be happy at first, but after a few years they will develop atrophy because the pressure is too high.

"If he or she is lucky it could be the right pressure, but it's a [gamble] today," Lamraoui said.

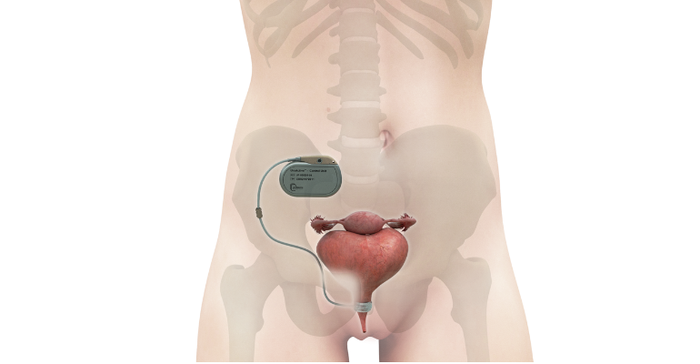

So, in designing the new device, the UroMems team decided to remove both the pump and the balloon, but they kept the urethral cuff. Instead of a pump and balloon system, the company developed a pacemaker-like control unit to automate the artificial sphincter device, as shown in the illustration below.

The control unit contains a unique bionic platform using embedded smart, digital, and robotic systems which, based on data collected from a patient, creates a personalized treatment algorithm. The core technology is what UroMems calls a MyoElectroMechanical System.

Developing this system for the control unit was easier said than done, however, because it needed to be hermetically sealed, fully biocompatible, and more efficient compared to the predicate device.

“Our success was based mainly on patience," Lamraoui said. "We were really patient.”

Collaboration is key

When asked to share a big-picture lesson that could be applied to other complex medical device projects that peers may be working on, Lamraoui said physician-engineer collaboration is key.

“The success so far is based on the fact that we work every day with physicians,” he said. “We have weekly meetings with surgeons.”

These meetings include at least two surgeons, sometimes more, who ask questions of the engineers and help to define user requirements and offer feedback on the development.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)