Always Take the Road Less Traveled

This week in Pedersen's POV, our senior editor takes us on a Hawaiian adventure and delves into the importance of risk management in medtech.

May 8, 2023

Risk management is part of our everyday life, even if we're not always deliberate about it. Sometimes it's as simple as deciding to cross the street. Other times we find ourselves evaluating a bigger risk – such as whether to drive a treacherous, cliff-hugging roadway explicitly prohibited by your rental car company.

This week, as I scrolled through my LinkedIn feed, I came across an interesting post from one of my favorite medtech influencers that reminded me of my Hawaiian adventure in 2016. Instead of joining Katie, my best friend and travel companion, on a helicopter tour one afternoon during our vacation, I set out to explore the West Maui Mountains.

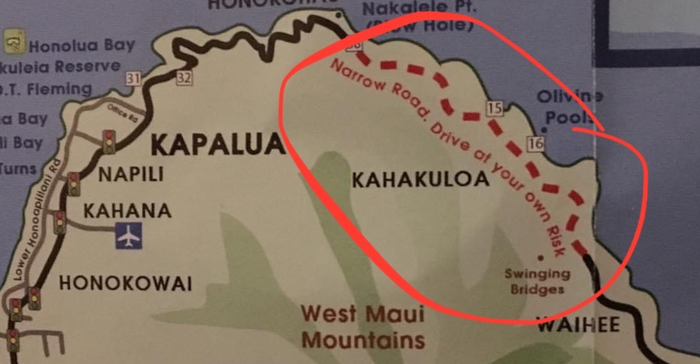

I was particularly interested in visiting Kahakuloa, a secluded area accessible either by private boat or by a very narrow and risky roadway connecting the town of Wailuku and Lahaina. Lacking a boat, my only option was to violate the rental car agreement (it was in Katie's name anyway). The fact that this stretch of road was marked "drive at your own risk" on my map made it all the more enticing.

Kahekili Highway is an incredibly narrow stretch of road (barely one lane, but with two-way traffic) marked by blind curves flanked by cliff on one side and sheer drop on the other. Without guardrails. It was indeed a heart-pounding, sweaty-palmed, white-knuckled drive. But damn, was it ever worth it.

At one point, I found a place to park and walked to the cliff's edge to watch the ocean waves crash against the rocky shoreline. I even braved the hiking trail down to see the blowhole at Nakalele Point close up.

So, when I came across Etienne Nichols' post asking, "What's the riskiest thing you've ever done?" I just had to share an abbreviated version of my Hawaiian adventure.

"Haha, so you can truly say, 'I took the road less traveled!' Bravo, sounds like the benefit outweighed the risk – I love it!" Nichols responded.

The medical device guru and community manager at Greenlight Guru is one of the few people in medtech who makes topics like risk management, design controls traceability, and global medical device regulation interesting.

In his recent post, Nichols uses the ISO14971 definition of risk: a combination of the probability of a harm occurring, and the severity of that harm. He also digs deeper into the various levels of severity and probability to demonstrate how a risk acceptability matrix is built.

Severity, for example, can be negligible (inconvenience, or temporary discomfort), minor (temporary injury or impairment not requiring medical intervention), major (injury or impairment requiring medical intervention), and critical (death).

There's no doubt that my "road less traveled" was a risk with a potentially critical outcome. There's a reason it's been dubbed "death highway of Maui."

The probability factor is much trickier to determine. News headlines like Vehicle Plunges 200 Feet off Kahekili Highway, Maui Woman Dies After Car Swerves off Cliff on Kahekili Highway are certainly unnerving. Reader's Digest ranks it 8/19 on its list of the Most Dangerous Roads in the World. Had I done my due diligence prior to this adventure – rather than seven years after the fact – I might have chickened out.

Let's look back at Nichols' post where he defines probability:

Improbably = 1 in 1 million

Rare = 1 in 100,000

Occasional = 1 in 10,000

Probable = I should probably stop commentating

Frequent = I don't even want to think about it

"The point is, it's up to you to link numbers to likelihood for your device," Nichols wrote. "Nothing beats real world evidence. And almost anything beats guessing."

He also notes that FDA's total product life cycle database (TPLC) has information to help inform your probability estimates. If you have a product code, you can research previous adverse events dating back 15 years. The TPLC database wouldn't have helped me determine the probability of driving off a cliff on the Kahekili Highway, but it is a great resource for medical device professionals.

Lacking hard numbers, I'm going to say the risk of a critical outcome on Maui's "death highway" is somewhere between rare and occasional. But there are many factors that must be considered to do a proper risk assessment. For instance, I'm a cautious driver and I took this journey during daylight in good driving conditions. Even my younger, thrill-seeking self would not have taken the chance if it had been dark or rainy.

Listen, I'm not telling you to take your life in your own hands every chance you get. But I will say, life is so much more gratifying when you mix in a bit of risk.

Of course, it's a bit different with medical devices because it's not your own safety you're dealing with, but the safety of other people. People who are trusting you to properly manage the risk of the medical device you're making.

A couple years ago, Greenlight Guru published a risk management benchmark study that uncovered some rather discouraging findings about risk management in the medical device industry. For example, 12% of the 363 respondents said risk management is viewed as a "checkbox" activity at their organization, meeting only the minimum requirements.

"The question is in our post-production review to review the risk management file, but there is a copy-and-paste statement that is being used and nobody actually reviews the risk management file," one respondent admitted.

Another respondent said they worry their organization won't adequately capture data to assess post-market risk prior to putting the product on the market, which could lead to patient harm. While the survey responses pointed to a theme of frustration that not everyone treats risk assessment with the care it requires, there also appear to be a lot of medical device professionals who care too much. By that I mean, 42% said they worry about product risk issues outside of their working hours, and 29% said it had a moderate or serious impact on their own quality of life.

There needs to be a better way to balance this important aspect of medical device development, without chasing people out of medtech.

One compliance officer complained that others in the organization did not engage in activities aimed at facilitating an open and ongoing dialogue around risks, which makes it difficult for them as a compliance officer to be proactive. So in this case, strengthening that process and creating a culture where employees are encouraged to have those types of discussions could be a smart move. In other cases, the problem might come down to a lack of proper tools and resources.

If you're at one of those organizations where risk management is merely a box-ticking activity, ask yourself this: how would you feel if your medical device was used on someone you care about? If that question is unsettling, it's time to rattle some cages until the problem is addressed.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)