How about Injecting Electronics into the Brain?

June 12, 2015

Researchers have created nanoscale electronic scaffolds that can be injected via syringe.

Chris Newmarker

|

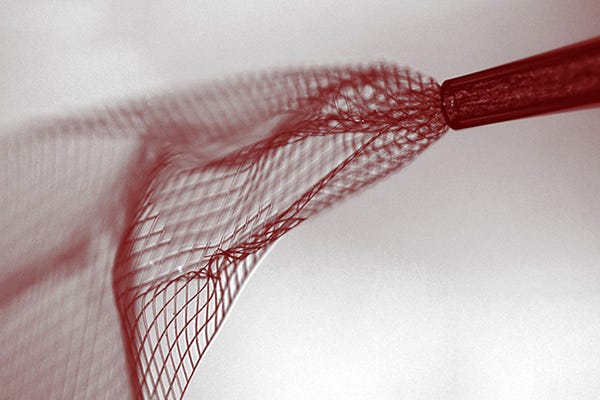

This bright-field image shows mesh electronics being injected through a sub-100 micrometer inner diameter glass needle into aqueous solution. (Image courtesy of Lieber Research Group, Harvard University) |

An international team of researchers may have hit on a solution when it comes to the invasiveness of probes placed in the brain--a major stumbling block when it comes to neural interfaces.

The researchers, led by Harvard University chemistry professor Charles Lieber, have created injectible electronics in a process similar to the way microchips are etched, according to a report from Harvard media relations.

It starts out with a dissolvable layer deposited on a substrate. Researchers laid out a mesh of nanowires sandwiched in layers of organic polymer. They then dissolved the first layer. The leftover flexible mesh can then be drawn into a needle and administered via injection.

Researchers say it is possible to connect the mesh to standard measurement electronics so that the integrated devices can then stimulate or record neural activity. Potential uses could include treatment of conditions ranging from neurodegenerative disorders to paralysis.

"I do feel that this has the potential to be revolutionary," Lieber told Harvard media relations. "This opens up a completely new frontier where we can explore the interface between electronic structures and biology."

Lieber and his colleagues first hit on the idea while experimenting with "cyborg tissue" of cardiac or nerve cells grown with embedded scaffolds.

"We were able to demonstrate that we could make this scaffold and culture cells within it, but we didn't really have an idea how to insert that into pre-existing tissue," Lieber said. "But if you want to study the brain or develop the tools to explore the brain-machine interface, you need to stick something into the body. When releasing the electronic scaffold completely from the fabrication substrate, we noticed that it was almost invisible and very flexible, like a polymer, and could literally be sucked into a glass needle or pipette. From there, we simply asked, 'Would it be possible to deliver the mesh electronics by syringe needle injection?'"

The next step is to better understand how the human body reacts to injectable electronics over longer periods. Harvard's Office of Technology Development has filed for a provisional patent and is seeking commercialization opportunities.

Refresh your medical device industry knowledge at MEDevice San Diego, September 1-2, 2015. |

Chris Newmarker is senior editor of Qmed and MPMN. Follow him on Twitter at @newmarker.

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to our daily e-newsletter.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)