The Surprising History Behind an Extremely Common Cardiovascular Medical Device

Trivia Tuesday: What commonly used cardiovascular device was first implanted in human patients in 1986?

March 5, 2024

Given how incredibly common coronary stents are today, it's surprising to realize that these tiny metal devices didn't make their debut in human arteries until 1986. Perhaps even more surprising, the coronary stent was essentially the result of an accident during an abdominal aortogram procedure.

The development of plain old balloon angioplasty

_3D_illustration.png?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

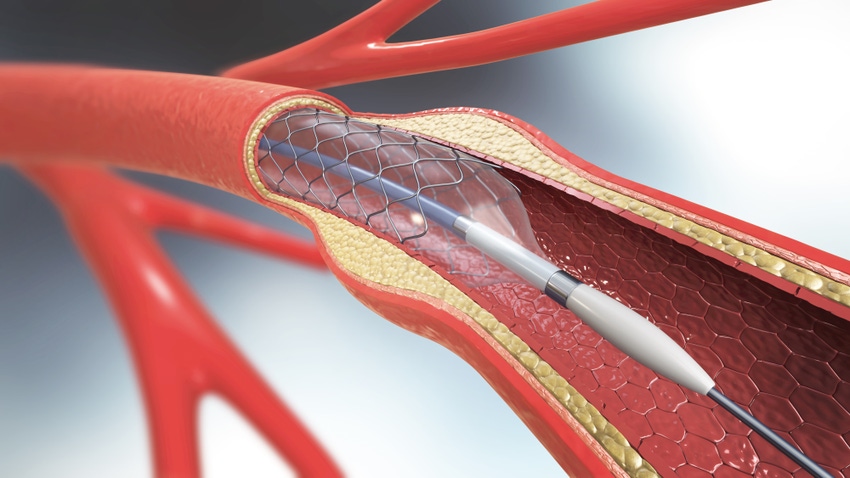

3D illustration of a balloon angioplasty procedure with a stent. IMAGE CREDIT: Mohammed Haneefa Nizamudeen / ISTOCK VIA GETTY IMAGES

Charles Theodore Dotter, dubbed "The Father of Intervention," and his apprentice Melvin Judkins accidentally "recanalized" an occluded iliac artery during an abdominal aortogram in 1963, according to an article on the history of coronary artery stents in the May 2018 issue of Revista Española de Cardiología, an international scientific journal and the official publication of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.

A year later, Benedetta Tomberli, et al. write that Dotter and Judkins intentionally used a catheter for the first successful percutaneous transluminal peripheral angioplasty. This led to the first balloon percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, more commonly known today as plain old balloon angioplasty, performed in 1977 by Andreas Gruentzig.

"Plain old balloon angioplasty can transiently achieve a larger luminal diameter by plaque extrusion, but elastic recoil rapidly obliterates this gain," the authors noted.

The development of the coronary artery stent

2002 tribute film on Julio Palmaz, MD. Producer: International Society of Endovascular Specialists, Director/Writer: Chris Wooley, Director of Photography: Wayne Dickmann.

The need to prevent arterial recoil and restenosis after balloon dilation is what ultimately spurred the invention of the coronary artery stent.

Jacques Puel, MD, and Ulrich Swigwart, MD, implanted the first self-expanding coronary stent in 1986. The following year, Julio Palmaz and Richard Schatz developed a balloon-expandable stent known as the Palmaz-Schatz stent, manufactured by Johnson & Johnson, which became the first FDA-approved coronary stent. J&J launched the stent in the United States in 1994.

Bare metal stents showed superiority over plain old balloon angioplasty, with elimination of abrupt occlusion and a reduced rate of restenosis, confirmed in the BENESTENT and the STRESS trials published in 1993.

The Palmaz tribute video above tells the story of how Palmaz crossed paths with Gruentzig, which began his journey toward inventing the coronary stent. Scroll down for video transcripts.

From bare metal stent (BMS) to drug-eluting stent (DES)

Later, cardiovascular device makers like Guidant, Boston Scientific, Cordis (then part of Johnson & Johnson), and Medtronic developed drug-eluting stents (DES) to tackle the ongoing problem of acute and subacute stent thrombosis.

The first drug-eluting stent was implanted in 1999, signaling the third revolutionary paradigm shift in the history of interventional cardiology, according to Tomberli, et al.

By 2006, DES safety concerns dominated the conversation at all the major cardiovascular conferences. Newer generations of these stents have shown better outcomes, however.

And of course, this story would not be complete without the mention of drug-eluting bioresorbable stents.

Bioresorbable stents: the disappearing act

Abbott was the first company to bring a drug-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS) to market, having received a CE mark for its Absorb BVS in January 2011 and FDA approval in July 2016.

But the Absorb BVS never enjoyed widespread adoption, and clinical data on the device was mixed. The device was also the subject of an FDA safety alert in March 2017 linking Absorb to a higher rate of major adverse cardiac events. So, it wasn't a complete surprise when, little more than a year after FDA approval, Abbott decided to take the Absorb BVS off the market.

The structure of the Absorb GT1 BVS was made of poly(L-lactide), a biodegradable polymer that dissolves over about three years, leaving the patient's artery free of permanent implants except for four tiny platinum markers in the artery walls denoting placement.

Abbott's CEO at the time, Miles White, described Absorb as a "very niche product," and he noted that physicians were more interested in a more deliverable stent than they were a bioabsorbable coated stent. So, the company turned its attention to the Xience Sierra, a follow-up to its Xience drug-eluting stent. The Sierra drug-eluting stent offered more sizes, better deliverability, and improved imaging tools.

Palmaz tribute video transcripts

Julio Palmaz: Through the literature I got interested in one particular author who eventually met and became my lifetime mentor actually it was Stewart Reuter.

Voice over: Stewart invited Julio into his radiology residency training program and eventually joined Reuters staff at the UC Davis Medical Center in Northern California. Julio continued perfecting his craft under Dr. Reuters masterful tutelage but it wouldn't be until a fateful day in 1978 when he would realize his true calling. For it would be on this day that Palmaz would cross paths with Andreas Gruentzig, the leader of a new pioneering therapy called balloon angioplasty.

Palmaz: A very important moment in my life was actually having the opportunity to hear Andreas Gruentzig as a visiting professor in 1978 in one of his first lectures in the United States. Gruentzig was very graphic in his descriptions, and he explained the limitations of angioplasty in such a way that anybody with a mechanical mind like mine was easy to elicit the concept of why not to place a metal mesh on top of a balloon and prevent all that.

Voice over: Unbeknownst to Palmaz, other physicians like Dr. Charles Dotter of the University of Oregon, had attempted to deploy coil-like artery supporters in vessels with little success. Perhaps naïve, but unquestionably inspired, Palmaz told an encouraged rooter of his idea. Unlike earlier failed attempts to develop such a device, Palmaz’s design would actually marry the Gruentzig and Dotter theories utilizing a balloon expandable mesh device that would stay in the artery to reinforce the vessel after the balloon was removed. Reuter sent his young protege to the lab to fulfill his quest.

Palmaz: I'd been playing largely at home with prototypes and things that I could do my own hands but the problem, I noticed that the main limitation was in miniaturization and needed special equipment.

Voice over: Equipment unavailable at UC Davis. But once again fate stepped in.

Palmaz: The University of Texas was offering me a significant amount of research time in my new job and also there was a machine within the campus that I could actually make this. So, all these facilities you know attracted me to Texas and I’ve been here since 1983.

Voice over: Reuter and Palmaz moved their practice to San Antonio without delay. Early prototypes newly tabbed by a medical journal editor as “the stent” were fabricated and ready to test.

Palmaz: I came here with a purpose of the developing the stent, so I had the sense of urgency of there was no time to waste. Within months after I arrived here, I had already implants in animals and by the end of that year I already had my paper ready for presentation and it got presented at the RSNA. We accumulated enormous amount of data that actually formed an important body of information that supported the clinical trials in that they proved feasibility for the FDA to approve these clinical trials. And then the long years of clinical trials followed.

Voice over: But the medical profession and industry were slow to respond. After all, hadn't this been tried before? And other newfangled modalities like the hot tip laser and atherectomy, devices which didn't leave a foreign metal structure behind were undergoing trials.

Palmaz: I already had run out of money, research money, the department had supported me to a great extent but obviously they were sending me out to get my own funds. But I had in the meantime the opportunity to meet another person that was doing a similar type of work, it was Richard Schatz. When Richard was exposed to the idea of a stent he loved it, but the most important thing is he did find for me a capital investor, was Phillip Romano, a person that was not in medical industry was actually a restauranteur, and Philip fell in love with the idea too, invested a significant amount of money only with the condition that a commercial entity be formed. Of course, being a businessman that is, he wanted to give a commercial frame to the project.

Voice over: The collaboration with cardiologist Schatz which inspired the extension of stent treatments into the coronary anatomy and the infusion of research cash by Romano provided Palmaz with the final ingredient for success. Soon a company, then not in the vascular business, came calling.

Palmaz: The first time that we had the opportunity to talk to a Johnson and Johnson representative they immediately felt attracted to the idea, it went along perfectly with their interest in getting into the vascular business, which at the time Johnson and Johnson was not, at least in the catheter area, and they wanted an interesting new project to get into the business rather than go the traditional way. What is fascinating is that Johnson and Johnson hired a consult company to help them decide whether they stand idea was a viable one from the business point of view, and they made the unanimous decision that was not a viable idea and it was a terrible proposition for Johnson and Johnson to get in. Nonetheless they disregarded the advice of the company, they went ahead and licensed it, and it became the most successful project, at least in in this area, that they have ever made.

Voice over: With strong backing by J&J, the stent took off. FDA trials – first in the iliac arteries, followed by other vascular anatomy – proved successful worldwide. Soon after, a study in the jewel of all arteries, the coronaries, set forth. But early in this study, Julio awoke one day in San Antonio to alarming news.

Palmaz: It was at the very beginning of the coronary trial when I heard, all of a sudden, that Mother Teresa, who I knew very well, got a stent. And the story goes that Mother Teresa was in Northern Mexico doing missionary work and all of a sudden developed heart failure, was brought to San Diego Scripps Clinic in an emergency basis and it got an angioplasty with a stent that night of admission. And the stent was still an experimental device and for her to receive one had to be incorporated as an experimental subject, which Mother Teresa obviously I acknowledged and accepted. So, the following morning when I learn of it, I definitely panicked for one thing because the stent was still in trials and I could see a headline saying, “Palmaz Stent Kills a Saint.”

Voice over: History has proven that Julio’s concerns were all for not. Mother Teresa, like countless other patients worldwide, had her health restored all due to an idea that has given birth to a revolutionary field now called endovascular intervention. And for the humble doctor Julio Palmaz, who still toils in his San Antonio research lab looking for an even better stent, his indelible mark on medicine will go down in history as one of the greatest of all time. Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome the International Society of Endovascular Specialists honoree for Excellence in Endovascular Innovation, Dr. Julio Palmaz.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)