TAVR: Still the Next Big Thing in Cardiology?

iPhone ECG inventor and cardiologist Dave Albert, MD, describes it as a “big deal.”Celebrity cardiothoracic surgeon Mehmet Oz, MD, calls it “a complete paradigmshift,” the cardiology equivalent of “landing a man on the moon.”For cardiologist Eric Topol, MD, of Scripps Health (San Diego), it is “a major step forward” that “will be a life-changer for many patients.”

June 29, 2012

PAGE 1 OF 2

iPhone ECG inventor and cardiologist Dave Albert, MD, describes it as a “big deal.”

Celebrity cardiothoracic surgeon Mehmet Oz, MD, calls it “a complete paradigm shift,” the cardiology equivalent of “landing a man on the moon.”

For cardiologist Eric Topol, MD, of Scripps Health (San Diego), it is “a major step forward” that “will be a life-changer for many patients.”

“It is probably one of the biggest new product launches in the cardiac device space since drug-eluting stents,” says Venkat Rajan, industry manager for Frost & Sullivan’s medical device team in North America.

It is TAVR, also known as TAVI (transcatheter aortic valve implantation). Available in Europe since 2007, the technology currently is only available to U.S. patients with severe aortic stenosis who are deemed inoperable. However, a much broader patient population could soon become eligible for the procedure.

“TAVR is indeed a game-changer,” says James Beckerman, MD, cardiologist at Providence St. Vincent Heart Clinic (Portland, OR). “It is maybe not [the cardiology equivalent to] landing a man on the moon—that will be the day we figure out how to prevent aortic stenosis. But in the meantime, TAVR will help more patients with critical aortic stenosis living longer, fuller lives.”

“TAVR is indeed a game-changer. It is maybe not [the cardiology equivalent to] landing a man on the moon—that will be the day we figure out how to prevent aortic stenosis. But in the meantime, TAVR will help more patients with critical aortic stenosis living longer, fuller lives.” |

Much of the enthusiasm is based on the fact that inoperable critical aortic stenosis was thought to be untreatable for decades.1 In aortic stenosis, calcium deposits hinder the opening of the heart’s aortic valve. “Having aortic stenosis is like standing on a plateau that is getting smaller with time,” Beckerman says. “As it becomes more severe, any wrong move—or any move at all once it becomes critical—sets you up for a long fall [from which it] is hard to recover.”

The problem is huge. Aortic stenosis is the most commonly diagnosed heart valve condition—roughly 300,000 patients worldwide, by conservative estimates, have been diagnosed with the disease. About one-third of them are not eligible for open-heart surgery. More than half of patients diagnosed with the disease die within two years, according to FDA.

Standard treatment for severe aortic stenosis is surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR). In this procedure, a patient’s breastbone is sawn to open up the chest and the heart is stopped. A clinician then removes the diseased valve and sews in a replacement. Performing the procedure typically lasts between six and eight hours and patient recovery time can last months.

By contrast, TAVR can be performed in an hour or two and patient recovery is typically a matter of days. Still, its clinical potential is uncertain. “My concerns are that we don’t know where to draw the line (such as in younger patients) and that it is a very expensive procedure approximating the cost of open-heart surgery,” Topol says. “I would have been even more excited about TAVR if this great innovation also dramatically cut the cost of replacing the aortic valve,” he adds. “Maybe someday?”

A Short History of Transcatheter Valves

The idea of minimally invasive valve replacement dates back to the late 1980s. In 1989 at an interventional meeting in the United States, Danish cardiologist Henning Rud Andersen, MD, claimed that heart valves could be implanted in a closed-chest procedure. After returning to Denmark, Andersen developed a valve-stent device with metal wire and pig valves from a butcher shop. He used the device in a pig to demonstrate the feasibility of the technique, and ultimately performed more than 40 valve-replacement procedures percutaneously in animals. The technology ultimately ended up benefiting his father, who had a transcatheter valve implanted.

The next TAVR breakthrough came in 2000 when renowned pediatric cardiologist Philipp Bonhoeffer, MD, performed the first human percutaneous heart valve implantation in a 12-year-old patient in France (although this procedure involved the pulmonary rather than aortic valve). The valve used in procedure, the Melody, was developed by Bonhoeffer in conjunction with Medtronic. The first transcatheter aortic valve replacement was performed on a human patient in April 2002 in Rouen, France, by interventional cardiologist Alain G. Cribier, MD.

Edwards Sets Sights on TAVR

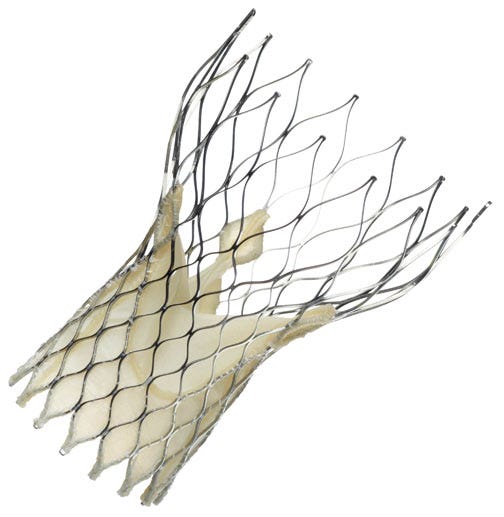

Intrigued by the technology’s potential, Edwards Lifesciences (Irvine, CA) became one of the first companies to pursue the commercial development of a percutaneous aortic valve. Shortly after the company was spun out of Baxter in 2000, the firm launched a small internal R&D project known as Patriot to investigate its potential. A couple of years later, Edwards learned of an Israeli startup, Percutaneous Valve Technologies (PVT), cofounded by Cribier, that was closer to commercializing TAVR than it was. Edwards bought PVT in 2004 for $125 million, and its first TAVR device, the balloon-expandable Sapien, was launched in Europe in 2007. To date, more than 30,000 patients have been treated with the Sapien and the second generation Sapien XT valve.

|

Sapien valves from Edwards LifeSciences have been commercialized in 47 countries around the world. More than 30,000 patients have been treated with the devices. Pictured here is the first-generation Sapien THV device, which was approved by FDA in 2011. |

CoreValve

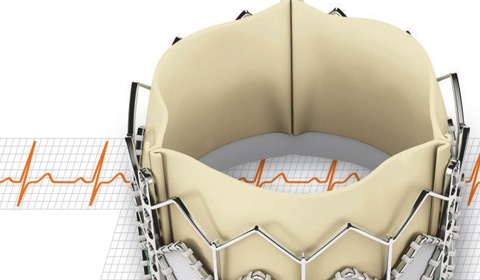

Medtronic also had launched an internal program to develop percutaneous aortic heart valves and sought to accelerate commercialization of the products through acquisition.

In 2009, the company acquired two TAVR firms: CoreValve (Irvine, CA), for $700 million, and Ventor (Netanya,

Israel), for $325 million. CoreValve, which was initially founded in Paris in 2001, was a venture-capital backed company that had launched a selfexpanding nitinol-frame TAVR platform in Europe in the spring of 2007; at the time, it was the first TAVR transcatheter aortic valve available in the world. Ventor, which was founded in 2004, had been developing an aortic replacement valve known as Embracer that can be delivered through the transapical approach as well as a percutaneous, transfemoral technology called Engager.

Although Medtronic ultimately spent significantly more on the acquisition of CoreValve than Edwards spent on PVT, both companies “got a fairly good deal,” Rajan says. “Edwards’ move in 2004 was probably a little riskier because the market wasn’t talked about as much at that time,” he says. “[No one] realized that this market was going to be as big as it is and have [such] potential,” he adds. “Edwards got into the market early at the right price. Once buzz started building and it was less of a risk, Medtronic had to pay a little bit more, but [it is] on the market in Europe and should be second to market in the United States.”

|

To date, more than 27,000 patients have received a CoreValve replacement valve in more than 50 countries outside of the United States. |

Rajan does not view being second to the U.S. market as a major disadvantage for Medtronic, especially when you consider

its presence in the cardiovascular marketplace. “Medtronic is equated with cardiac treatments,” Rajan adds. “Unless Edwards has some kind of safety issues, it should hold the top share, but Medtronic should pick up a good chunk just because so much of the market is unaddressed,” he says. “Both Edwards and Medtronic are highlighting transcatheter valves as flagship opportunities for the next five years and outward.”

Part 1 | 2 |

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like