Elements of Project Excellence

Originally Published MDDI February 2006Product Development Insight OEMs have the power to make the product development process more efficient and to make the process yield better products. Such improvements can stem from cultural changes. Mike PeglerPRTM

February 1, 2006

Product Development Insight

Product development is the lifeblood of the medical device industry. Patients look to device makers to improve quality of life and to ensure that safe, effective products are developed and manufactured. Shareholders expect OEMs to build company value by developing innovative new products predictably and efficiently.

Product development is the lifeblood of the medical device industry. Patients look to device makers to improve quality of life and to ensure that safe, effective products are developed and manufactured. Shareholders expect OEMs to build company value by developing innovative new products predictably and efficiently.

OEMs need to evaluate product development performance and ensure they are meeting the demands of the patients and the shareholders. The questions that device makers need to ask themselves are simple:

• How effective is the product development process?

• Are new product development projects on schedule, or are they late and underresourced?

• Are products a result of strong companywide collaboration, or is it a fight to get a product out the door?

• Is the postlaunch period smooth, or do product designs need years of tweaking to reduce costs or better address patient needs?

Achieving acceptable answers to these questions often requires a new approach to the product development process. One such approach may be to adopt the principle of project excellence. In the device industry, OEMs have strict regulations governing design control, and device makers must be diligent about following those guidelines. But there are no such rules mandating an efficient, businessfocused development process. The methods to create such a process must come from executive management and should be included in every step of the development project.

What is Project Excellence?

Project excellence comprises cross-functional processes, project decision making, and team organization that enable firms to bring high-quality products to market rapidly. Project excellence builds on functional excellence (i.e., when a function has the necessary resources, along with standards, procedures, and tools, to be effective and efficient). Four major elements are required to deliver projects effectively. These elements include the people and processes involved in development. Project governance, a defined development process, project core teams, and the project decision process are the four elements. Although the concepts discussed here are not revolutionary, surprisingly few companies have all four elements working well.

Some companies cherry-pick particular product development practices but do not put in the mechanisms to ensure that projects are adequately funded, staffed, and coordinated with other projects in the pipeline. For example, a medical device company that had designed a product for home use claimed to have mastered project excellence. A closer look at its processes revealed critical flaws. The company had not established a forum for making project decisions, such as budget approval, regulatory strategy, and device function. Its project teams were large, with more than 30 people appointed to each. Furthermore, the teams were not balanced. There were too many people from engineering, while other departments were underrepresented. Status meetings were time-consuming, and decision-making processes were unclear. The result was a slow development process. In this case, the people involved got stuck in loops around the issue of product definition.

Unfortunately, this scenario is all too common. Another case involving a component manufacturer provides a clear illustration of how executive oversight and development activities can become disconnected. The chief operating officer (COO) attended a trade show and discovered that the centerpiece product at his company's booth was a product that he didn't know his company had funded or developed. It is critical that executive oversight and development activities stay connected.

Project excellence can be achieved only via smooth coordination and balance. It is important to embrace all aspects of refining the process. Firms may think they are doing a good job, but when they really take the time to evaluate their development process, they may find otherwise.

The Building Blocks

A defined development process maps the cross-functional steps from concept through launch, including requirements definition, prototyping, testing, clinical studies, and regulatory approval. Defining the terms of development helps ensure a common level of understanding and terminology between project teams and functions. It also helps define the expectations for teams and executive management.

It is helpful to think of a project schedule at differing levels. The highest level would be the phases, followed by steps, tasks, and activities. The details of phases and steps are best described in an overview chart of the defined development process (see Figure 1). Tasks and activities, which are usually more detailed, can be captured in a Gantt chart developed by core team members, as they pertain to each member's area of expertise. This holistic perspective allows project teams and executives to communicate the project's current status.

|

Figure 1. From concept to launch, review sessions need to be scheduled frequently, as shown in this flow chart. |

A well-defined development process should integrate design control. But reliable design control alone does not ensure a business-focused and efficient process. It is not enough to have solid design controls without a sound business process.

In some cases, having a defined development process can improve design control. For example, an often-overlooked part of design is repeatability. Developing and using standard templates for key documents can prevent the need to start over for each new project. Many companies do not leverage standard templates as effectively as they could.

Project core teams are small, cross-functional groups that spearhead development projects through each phase of the process. A project core team must represent the firm and drive successful development of the products in its scope. It provides a forum to balance the three key functions of any development plan: sales and marketing, operations, and engineering. Juggling these three functions is not easy.

Each functional area has its own concerns and interests. The sales and marketing departments very often don't want to be bothered with the details of supply-chain challenges and development timelines. They want the product to be available now, with all the features and variants that customers ask for. The operations group is concerned with running factories at high yield and high utilization. Their goals are met through an unchanging demand forecast and a single standard product. And there is often the perception that engineering would like to develop the latest cutting-edge technology, and that they are not concerned with timelines or budget. Of course, these examples would be extreme cases, but it is true that the goals of each group conflict with the others. However, when these competing aims are met through cross-functional planning and execution, core teams can deliver a real-world product that balances the needs of all three functions.

When a dedicated cross-functional team is not put in place, the consequences can be disastrous for a company. For example, at one small (35-person) medical diagnostic company, engineers were working on the company's first commercial product. The product was a digital x-ray scanning system and the engineers were trying to improve the scan rate, even though customer feedback actually said that it was already good enough. The company ran out of funding before the product could be brought to market. This was an extreme result of the dreaded scope creep that most companies have experienced to one degree or another. The desire for increased scope or functionality must be balanced with the other project factors: scheduling, budget, quality, and cost. All these factors are partly determined by the role and context of the project relative to all the other projects in the pipeline.

|

Figure 2. Participants in a core team should come from various disciplines. |

Effective project core teams have between four and eight members, with each leading one aspect of the project. Having more than eight people tends to impede nimble decision making. Having fewer than four people means the team may not adequately represent the main functional areas. Some companies have so-called core team meetings with 20–30 attendees. It's difficult for a group that large to agree on what time to take a coffee break. Figure 2 shows a typical effective core team.

One of the first steps that the project core team should take is to identify all the functional areas of the project and assign responsibility for each to one person. It can be very helpful to go through the simple exercise of assigning responsibilities, particularly in large or complex organizations.

The project core team must remain together throughout the product development cycle. Keeping the team together enables a cohesive, high-performance approach. And including representatives from all relevant functions as project core team members from the beginning enables several valuable outcomes. For one, the team can incorporate design for x thinking into the product. In this way, x can be anything the manufacturer needs, including manufacturability, quality, or cost. In addition, functional experience and user feedback can be built into the process from the beginning. For example, if users have a hard time opening the vials of test strips that work with the in-house test meter, manufacturers should ask questions about how to modify the design of the vial cap to make it easier for the target population to open.

Finally, a key attribute of successful project core teams is a strong core team leader. The leader should be familiar with all attributes of the product and be able to provide guidance to the core team throughout the development cycle.

The project governance team is a separate senior management team that oversees new product development and allocates the resources (both human and monetary) for execution. A typical example of this team's makeup is shown in Figure 3. Ideally, the project governance team has between five and eight people. It usually includes representatives from finance as well as functions like regulatory affairs and engineering. The project governance team should define portfolio strategy, ensure a balanced pipeline, charter new projects, and reapprove projects at each decision point.

|

Figure 3. Although separate from the core team, the governing team should be well- versed in the core team's activities. |

The governance team faces some potential problems that it should strive to curtail. Some teams get too caught up in the intricate details of the project. If that happens, the team may ignore corporate strategy and lose sight of the big picture of the portfolio. Other governance teams may be too hands-off in their approach. If they expect core teams to make development happen, they might ignore issues concerning critical resource sets. They may continue to reapprove projects that the development pipeline simply cannot support.

It is also crucial that governance teams understand the role of design and technical reviews, ensuring that these are conducted at the proper points in the development process.

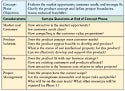

The project decision process, a formal, event-driven evaluation, enables the governance team to review a project and determine whether to reapprove it. The team will also decide on the next phase of development and assign resources. Before chartering new projects, this team asks questions about the market, the customer, the product solution, and so on. Sample questions are shown in Table I.

|

Table I. Before continuing a project, participants should be able to answer certain questions to decide what course the project should take. |

At each predefined decision point in the product development cycle, the project governance and project core teams should formally meet. They need to ensure that the current phase was completed satisfactorily, that key questions have been answered, that key deliverables are completed, and that the project still makes sense given the overall opportunity and portfolio context. Based on the recommendations of the core team, the project governance team makes a go/no-go decision. If a project is reapproved, it then proceeds to the next phase of development and is assigned the required resources. If the team decision is a

no-go, the project is canceled and the resources are freed up to work on other projects. A third option is to redirect the project but take it in a different

direction.

During each formal meeting, the project governance and project core teams should set a time for the next phase review. This is also the time for the project governance team to ensure that issues involving intellectual property, trademarks, single-sourced components, and high-level design issues have been addressed.

To maintain scope, schedule, and cost of the project, many companies find it helpful to draw up a contract that provides variances to the key parameters of each group. So, when the project governance team makes a go decision, the project core team operates within the variances laid out in the contract.

As long as those principles are observed, the core team can drive its project forward without the need for a formal check-in until the next agreed review. After any significant redirect decision, the core team should be given time to reconsider the revised plan. A new contract between the core team and the governance team should then be proposed.

In addition to the four elements depicted in Figure 1, there are metrics and tools that enable the goal of product excellence to be achieved. For example, resource management tools highlight and quantify resource conflicts. Product development metrics (e.g., development cycle time) allow project core teams to use past experience to better predict the development schedule. It is critical to train all team members to use these tools, in addition to training members on implementing the team approach. Such skills are especially critical after project kickoffs, when new people may join either of the teams.

A Note on Innovation and Human Factors Although this article is primarily concerned with the organization of the product development process, it should be said that innovation and human factors work in concert with product development. Combining both art and structure to the process yields far greater products than either one alone. As competition increases and profit margins are squeezed, it's imperative that firms have a good handle on improving innovation and increasing R&D productivity. Despite the need for a level of structure and process around product development, companies need to remember that there is an art to creating a successful product. Innovation and R&D productivity have never been more important to the profitability of medical device companies than they are in today's competitive environment. Firms should be on the lookout for innovative ideas that can be incorporated into products—even from other industries. Central to product excellence is the need to satisfy specific customer and user needs. The process should be designed to ensure an early, thorough understanding of and agreement on the customer and user needs, whether through formal processes, such as the voice-of-the-customer approach, or through informal methods. At minimum, such methods should include mandated human factors activities and a review of relevant medical device reports (MDRs), customer service complaints, feedback, and an analysis of returns. OEMs may find that creating forums internally can foster innovation. Innovation can boost the success rate of new products and increase revenues. Productivity enables a company to maximize the value of scarce resources and increase R&D output. Addressing productivity and innovation creates a powerful lever for driving increased profits. Using such techniques as observational research and voice of the customer and engaging with customers and users, even those that did not purchase products, can yield a host of insights that can lead to breakthrough products. Usability testing of the product can yield additional enhancements and refinements, too. |

Achieving Project Excellence

Understanding the elements of project excellence is only one part of ensuring that the approach succeeds.

It's imperative to gain senior management buy-in and support for the initiative, both in word and deed. Senior managers must agree that the approach is the right thing to do for the company. They must be certain that the reduced development cycle time, increased efficiency, and better-designed products are worth the investment in time and attention. Companies that have used the approach effectively have dedicated significant time to sketching out the high-level design of the four elements. They then identified team members, people from various disciplines with the appropriate levels of experience, to create a process design team to define and implement the details of the new process.

Given the far-reaching implications of product development throughout an organization, it is critical to recognize that project excellence is a cross-

company effort, and it could require a significant cultural change. Such a change cannot be brought about overnight; it requires continuous sustained focus. Cultural change is best supported through visible leadership from executive management.

Continually updating the organization demonstrates the importance of the new approach and will help reinforce the message. Someone must manage the up-to-date process guidelines, templates, and training materials, and oversee the way new methods are incorporated. A few early wins from successful pilot projects can also help cement the new approach in the company's culture. Although benefits will be realized almost immediately, the real payback comes only when project excellence is part of the corporate culture and has the sustaining ownership and support mechanisms to keep it well tuned.

Copyright ©2006 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)