FDA Guidance on Review Procedures Made Available

Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry MagazineMDDI Article IndexOriginally Published January 2001WASHINGTON WRAP-UPFDA explains methods for identifying and responding to deficiencies. James G. DickinsonAlso:

January 1, 2001

Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry Magazine

MDDI Article Index

Originally Published January 2001

FDA explains methods for identifying and responding to deficiencies.

Also:

Is FDA Biased against EU Devices?

SUD Reprocessing Enforcement

New Vascular Graft 510(k) Guidance

According to a November 10 guidance document, CDRH reviewers should use a four-part approach when identifying deficiencies during the course of a premarket approval (PMA) or 510(k) review. The guidance, Suggested Format for Developing and Responding to Deficiencies in Accordance with the Least Burdensome Provisions of FDAMA, says the reviewer should do the following:

Clearly identify the specific issue.

Acknowledge the information submitted and explain why that information did not adequately address the issue.

Establish the relevance of the deficiency to a PMA determination of "reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness" or a 510(k) determination of "substantial equivalence."

Request the necessary additional information needed to adequately address the issue and, when possible, suggest alternate ways of satisfying the issue.

The guidance also provides models for reviewers to use. The following, excerpted from the guidance, should be used for a PMA deficiency related to determining reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness.

(1) According to your Investigational Plan, your device is intended to fuse a bone fracture by the 24-month follow-up assessment.

(2) You reported that 55% of the study subjects had been followed for 24 months. We are concerned that a meaningful statistical analysis cannot be conducted on this study cohort.

(3) To thoroughly evaluate the effectiveness of your investigational device, the data set should be complete enough to have sufficient statistical power when compared to the control group.

(4) Please continue to follow your study subjects until you have sufficient statistical power at the 24-month follow-up point.

The document outlines a 510(k) deficiency in the following way:

(1) In your submission, you proposed to use your suture anchor for repairs of the rotator cuff and ankle ligament.

(2) You have submitted all of the appropriate testing with the exception of "pull-out" testing for the anchor. We believe that this testing is needed in order to fully characterize the performance of the device.

(3) "Pull-out" testing will help to ensure that the device can adequately handle the physiological loading experienced by the rotator cuff and ankle joints.

(4) Please provide a complete test report for this testing or justify why it is not necessary.

In addition, the guidance provides recommendations and a format for sponsors to follow when responding to deficiency letters. "In developing a response to a deficiency, industry should first provide an exact copy of the agency's question to remind the reviewer of the information that had been requested," the document says. If the deficiency is a follow-up question to an earlier deficiency, manufacturers should include both the original and follow-up question. Extensive responses should be organized for easy access with a table of contents, list of figures, and list of tables. "A description or justification of how the information adequately addresses the agency issue is advisable, unless obvious," the guidance adds. When referencing a standard in lieu of data, identification of the standard, its revision date, applicable sections, and any deviations from the standard should be included.

If a sponsor disputes a more-information request as not relevant to the regulatory decision, then the sponsor should articulate this position in the response, the guidance says. Alternatives can be provided by the sponsor "to optimize the time, effort, and cost of reaching resolution of the issue within the law and regulations. This could include alternative types of bench testing, proposing nonclinical testing in lieu of clinical testing, the use of standards, etc." The following is an example of a sponsor response to the above PMA deficiency example:

FDA requested that additional study subjects be evaluated at 24 months to ensure a meaningful statistical analysis at the 24-month follow-up point. To date, 30 additional study subjects have reached the 24-month follow-up assessment, bringing to 75% the percentage of study subjects that have been evaluated at 24 months. Please find on the following pages: a) an analysis of the 24-month data representing 75% of the study subjects, and b) a rationale supporting 75% as an adequate percentage of the study cohort to allow meaningful analysis.

The new guidance may be accessed at http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/modact/guidance/1195.html.

Is FDA Biased against EU Devices?

An analysis of 10 years of FDA warning letters with product detentions issued to medical device manufacturers in Europe—when compared with similar actions against U.S. firms—"demonstrates a remarkable bias against European device manufacturers," according to Washington, DC, attorney Larry R. Pilot (McKenna & Cuneo). Pilot says he made the analysis for a presentation he gave in October to the annual general assembly of Eucomed, the European medical device industry association, in Berlin.

In the 1991–2000 period, Pilot says, about 238 warning letters were received by 200 European manufacturers, of whom about 120 were notified that their products may be detained upon entry to the United States. This contrasted with the equivalent experience of U.S. manufacturers, Pilot says. In the 1991–96 period, they received 2995 warning letters but only 141 seizures and 32 injunctions. Unless there are multiple seizures or a contrary court order, Pilot says, a U.S. manufacturer whose devices are seized may continue to ship them.

Pilot contends that the heavy hand CDRH applies to European manufacturers is not shared by its drugs counterpart, CDER. Since 1991, FDA's drug center sent 18 warning letters to firms in Italy, Germany, France, and England, but only four of those contained an explicit reference to CDRH-type detentions, he told Eucomed. "If the FDA detentions represent a barrier to trade for which there is no justification that is reasonably related to safety or effectiveness, the EU and member states need to express their views."

CDRH director David W. Feigal told this writer that Pilot's assumption that device manufacturing is of equal quality throughout the world was "dubious." He said the fundamental issue was that while the agency does GMP inspections every three to four years in the United States, it only performs them every 10 to 12 years at foreign sites. "A much higher proportion of these are for-cause when we have such infrequent inspections," he said. "So the violation proportion would be expected to be higher. I think you could argue that the lower inspection rate abroad discriminates against U.S. firms."

Feigal also noted that Pilot's Eucomed presentation "was a mixture of time frames. He presented 10-year European data and five-year U.S. data. The 10-year data capture the Kessler years when the proportion of inspections overall with warning letters was 20 to 25%. Over the last five years the rate has been half that, so the way he showed the data was almost sure to show a lower rate. He also didn't have any denominators."

A critique of Pilot's charges prepared at Feigal's request by CDRH's Office of Compliance called them "misleading because of what he is comparing. He compares 120 import detentions over 10 years to 12 domestic detentions over an almost 10-year period." The critique went on to say:

Domestic detentions are not the same thing as foreign detentions. Foreign detentions are put into place and remain in place until the firm corrects the problems. They can be in place for years. On the other hand, the domestic detention is used very sparingly and typically only to gain control over product that we have reason to believe will be intentionally shipped by the affected firm or others. This action is usually taken when there are other compelling circumstances such as when the device represents a public health risk. In the last 25 years, we have taken probably no more than 50–60 such actions. Administrative detention also places a significant due process burden on FDA. For example, once we detain, the firm can appeal and within five working days of the appeal, FDA has to hold an administrative hearing (usually presided over by a regional director) and present our case. We've had a few hearings and it has been a significant challenge to meet these deadlines.

The office said automatic detentions are the only viable action the agency can take after issuing a warning letter to a foreign firm. "We consider that action to be a comparable enforcement tool to an injunction more so than a product seizure on the domestic side," the office said. An injunction, like a detention, immediately stops the firm from shipping product in U.S. commerce. "A seizure only captures specific goods that we identify are violative but does not specifically prohibit the shipment of new product (although we can and have amended seizures to injunctions when shipment continued after a seizure). When considering a detention, we should always ask ourselves whether the deficiencies would warrant injunction domestically." The statement said the office is doing this "fairly consistently."

On Pilot's additional charge that CDRH is more severe in its foreign warning letters than FDA's drug center is in similar situations, the CDRH Office of Compliance said it has asked the FDA Office of Regulatory Affairs for comparative data on this. It also noted that direct objective evaluation of Pilot's data was made difficult by missing data and old records in FDA's system that have not been computerized.

SUD Reprocessing Enforcement

CDRH's PMA enforcement deadlines for hospitals that reprocess single-use devices (SUDs) were provided in a recent agency letter. In it, CDRH listed its enforcement dates for premarket submission requirements: February 14, 2001, for all Class III devices; August 14, 2001, for all nonexempt Class II devices; and February 14, 2002, for all nonexempt Class I devices.

CDRH added that it intends to enforce the nonpremarket requirements (i.e., registration and listing; the quality system regulation; medical device reporting; labeling and tracking; and corrections and removals) by August 14, 2001. CDRH also stressed that hospitals should pay particular attention at this time to the regulatory requirements for GMPs: "Any hospital that intends to continue reusing and reprocessing SUDs will need to understand these requirements, which include process validation, corrective and preventive action, quality system inspection, and controls used for packaging, labeling, storage, installation, and servicing of all reprocessed SUDs."

Shortly after issuing the letter, CDRH posted to its Web site a list of SUDs (designated appendix A) known to be reprocessed, which was taken from the August 14, 2000, Guidance for Industry and for FDA Staff: Enforcement Priorities for Single-Use Devices Reprocessed by Third Parties and Hospitals.

The guidance can be found at http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/reuse/1168.html, and the appendix at http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/reuse/1168a.html.

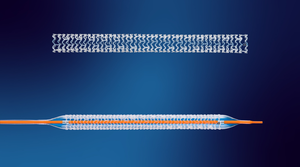

New Vascular Graft 510(k) Guidance

FDA's latest views on special controls for vascular graft prosthesis 510(k)s can be found in a new agency guidance document. The guidance was "developed to support the reclassification from Class III to Class II for vascular graft prostheses of less than 6 millimeters in diameter . . . and also applies to vascular graft prostheses of 6 millimeters and greater diameter."

It reminds all manufacturers that they must comply with the quality system regulation and identifies a host of significant overall controls they should be aware of, from design controls to test equipment.

Key steps in process validation are also noted, including acceptance activities and preventative action, as well as certain risk factors—thrombosis embolic events, occlusion stenosis, and more. Their appropriate controls are also included.

The guidance may be accessed at http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/ode/guidance/1357.pdf

.

James G. Dickinson is a veteran reporter on regulatory affairs in the medical device industry.

To the MDDI January 2001 table of contents | To the MDDI home page

Copyright ©2001 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like