FDA and the Temptations of Expanded Authority

Originally Published March 2001WASHINGTON WRAP-UPProposed rule establishes procedures that the agency will follow to rescind 510(k) clearance decisions.James G. Dickinson

March 1, 2001

Originally Published March 2001

Originally Published March 2001

WASHINGTON WRAP-UP

Proposed rule establishes procedures that the agency will follow to rescind 510(k) clearance decisions.

James G. Dickinson

$60-Million Consent Decree

$1.5-Million Laser Settlement

Prosthetic TMJ Devices Returned to Market

Ethicon Issues Electrodes Safety Alert

If you ask FDA to spell out the limits of its authority over some vague area, don't be surprised if the agency's attention to the matter has the opposite result—a power grab. That's the bureaucratic version of the old maxim that "nature abhors a vacuum," as AdvaMed (formerly HIMA) discovered when FDA formally proposed to issue a regulation giving itself authority to rescind previously cleared 510(k)s.

According to the proposal's preamble, it all started in 1994, when HIMA asked the agency to issue an advisory opinion to the effect that FDA does not have the authority to rescind a 510(k), or to set out the basic rights of manufacturers if the agency believed it had the authority.

After due consideration, FDA found the additional authority irresistible and claimed it in a 1995 letter to HIMA. Not to seem too greedy, however, the agency said its decision was only an interim response and that it intended to issue a proposed rule to consummate the decision. The agency further stated that, "pending the completion of this rulemaking process, FDA would only rescind, or propose to rescind, substantial equivalence orders in cases involving: a serious adverse risk to public health or safety, data integrity or fraud, or other compelling circumstances."

After five years of further cogitation, FDA published the proposed rule in January; however, it establishes six explicit reasons to exercise its expanded rescission authority.

In the proposed rule, FDA says its authority to rescind a 510(k) is derived from its general administrative procedure regulations that allow the agency to "at any time reconsider a matter." Moreover, it says, case law "also supports FDA's authority to correct inappropriate decisions." It cites a 1990 case, American Therapeutics Inc. v. Sullivan, in which the court ruled that FDA must be given latitude to rescind a drug approval that had been issued by mistake.

Therefore, FDA says, if a 510(k) is found to have been cleared in error, a registered letter will be issued to the 510(k) holder of record proposing rescission of the order of substantial equivalence. The agency will also post notice of the proposed rescission on the CDRH Internet home page.

FDA states that this action will only be taken in one of six circumstances:

The premarket notification does not prove the device has the same intended use or the same technological characteristics as the predicate device.

Based on new safety or effectiveness information, the device is not substantially equivalent to a legally marketed device.

Predicate devices have been removed from the market by FDA or the 510(k) holder for safety and effectiveness reasons, or a court has found them to be misbranded or adulterated.

The premarket notification contained or was accompanied by an untrue statement of material fact.

The premarket notification included or should have included information about clinical studies that failed to comply with institutional review board or informed consent regulations, so that the rights or safety of human subjects in clinical trials supporting the device were not adequately protected.

Clinical data included in the premarket notification came from a disqualified investigator.

FDA's proposal states that the agency does not intend to rescind 510(k)s without giving the holder of record at least three days' notice by registered mail. The notice must state the basis for the action and provide an opportunity for a hearing. An exception can be made if immediate action is deemed necessary to remove a dangerous device from the market. The proposal explains, however, that in the event there is need for immediate action, "FDA may, for example, attempt to contact the 510(k) holder by telephone instead of registered mail."

Because medical device products change ownership under normal marketplace conditions, FDA's proposal recognizes that the agency may not be able to find the 510(k) holder of record when a clearance is to be rescinded. Nevertheless, "notification by Internet site would serve as an additional means of assuring that the current holder has notice," the agency contends. In such cases, FDA will consider the failure of the holder to respond to be a waiver of the right to a hearing and will issue the rescission order.

FDA says it does not expect the rescission rule to have a significant economic impact on the industry, noting that it proposed only five rescissions from 1997 through 1999, and only one through May 2000.

Four harrowing accounts of corporate indifference to consumer suffering are detailed in a $60-million plea agreement signed on December 15, 2000, by Johnson & Johnson's medical device subsidiary, Lifescan Inc. (Milpitas, CA). The company pleaded guilty before U.S. district court judge Jeremy Fogel to three misdemeanor charges stemming from defects that the firm knew to exist in its SureStep blood glucose monitors. Specifically, Lifescan agreed that it had marketed misbranded devices, failed and refused to file required reports with FDA, and submitted false and misleading 510(k) information to the agency.

At the heart of the problem was a computerized meter that was found to have two distinct defects capable of causing problematic displays. A software defect caused the SureStep device to sometimes display an error message (ER1) instead of "HI" when the user's blood glucose level exceeded 500 mg/dl, and to always display the incorrect message at levels above 600 mg/dl. The second defect was found to occur when the monitor's test strip was improperly or incompletely inserted. Incomplete insertions were found to result in readings that were as much as 90% less than the user's actual blood glucose level. Even though the company knew of these problems, and against repeated recommendations of its own clinical director, Lifescan continued to promote the device to "users who had difficulty in testing, including persons with shaky hands or arthritis, and persons who wanted to 'be sure at every step,'" according to the government attorneys.

Court documents indicate that during 1996, 1997, and 1998, Lifescan received more than 2000 SureStep customer complaints of inaccurate low readings, some of which were attributable to incomplete strip insertion, and more than 700 complaints regarding error messages, some of which were attributable to high blood glucose. According to the plea agreement, Lifescan received at least 61 error complaints that were associated with consumer illness or injury, including some hospitalizations.

Among the four anonymous consumer injury examples cited in the plea agreement was a patient who complained of getting ER1 messages and was guided by Lifescan's customer service representative through a meter test on the telephone that duplicated the ER1 result. Lifescan recorded the complaint and sent the customer a new meter, without informing the user of the ER1 defect. The replacement meter exhibited the same defect, with the same response from the company—another report taken and a replacement sent, but no explanation of the defect. The third device also displayed multiple ER1 messages instead of numerical readouts. The user, however, reported receiving a reading of 249 mg/dl prior to suffering vomiting, excessive urination, and dehydration, and required hospitalization. The user was diagnosed with ketoacidosis resulting from hyperglycemia, according to the plea agreement. This time, Lifescan requested that the meter be returned, and its director of clinical evaluations, a medical doctor, recommended an immediate medical device report (MDR) filing with FDA and a recall of the SureStep meters because they posed an unacceptable risk of harm to the public.

Lifescan admitted that it failed to advise consumers of the two defects and failed to file MDRs on some of the illnesses and injuries. In June 1998, the company initiated a voluntary recall of all SureStep meters produced before July 27, 1997. FDA classified the action as a Class I recall.

In addition to the $60 million in criminal and civil penalties, and among other conditions of probation, Lifescan is required to:

Provide FDA with monthly reports and analyses of seven categories of complaints received and the disposition of those complaints.

Conduct extensive new validation testing of the SureStep meters according to nine explicit parameters and provide the results to FDA. If the product is found to fail to meet its performance specifications, if such nonperformance cannot be remedied, and if FDA submits a written request, the devices will be removed from the market immediately.

Hire an outside auditor to assess all of its manufacturing operations for compliance with FDA requirements.

Reimburse FDA for all its supervision, inspection, and compliance costs arising from the agreement.

Provide its directors, management, employees, and "associated persons" with full details of the special conditions agreed to, and present these personally at general meetings and in written form.

Former FDA commissioner Jane Henney was quoted by the Justice Department as saying the agreement "shows that FDA is serious about enforcing the law. . . . Defective products that give inaccurate or misleading readings will not be tolerated, and we will take action against firms that market them."

Laser Vision Centers Inc. (St. Louis) reached a $1.5-million settlement with FDA in January over an administrative complaint that the agency filed against it in April 2000 concerning the prior use of the firm's "international cards" software. That software enabled LaserVision's excimer lasers to be used in eye surgeries for higher myopia cases (greater than –6.0 diopters) than were covered by the initial FDA approval. The agency later approved the use of an excimer laser for higher myopia cases.

No details of the settlement have been released by FDA. Despite agreeing to settlement, however, the company states that it has been unfairly singled out because "other laser operators engaged in the same practice were not the subject of FDA enforcement and there were other mitigating circumstances." The company contends that "FDA acted in a manner inconsistent with its stated guidelines, which provide for the agency to issue warning letters to alert individuals that a practice may not be in accordance with FDA's standards." The firm also notes that the settlement contains "no finding of any wrongdoing on the part of the company or any of its executives."

After a 19-month forced absence from the market, Colorado-based TMJ Implants Inc.'s metal-on-metal temporomandibular joint (TMJ) total prosthesis received FDA approval on January 5. This action leaves the company's more popular condylar partial joint still to be approved. TMJ Implants CEO Robert Christensen says his company's future depends on the partial device. Both of the preamendment "grandfathered" products were removed from the market in 1998 during a device classification process that turned adversarial.

Investigations by Congress and the HHS inspector general's office are believed to be under way on Christensen's allegations that staffers in CDRH's division of dental, infection control, and general hospital devices were biased in their handling of the two Christensen devices, causing the firm to lose market share. The same reviewing division was censured in 1997 over similar allegations involving dental monitoring devices marketed by Myotronics Inc.

Christensen's total joint was approved for inflammatory arthritis involving the TMJ not responsive to other modalities or treatment; recurrent fibrous or bony ankylosis not responsive to other modalities or treatment; failed tissue graft; failed alloplastic joint reconstruction; and loss of vertical mandibular height or occlusal relationship caused by bone resorption, trauma, developmental abnormality, or pathologic lesion.

The approval was made subject to two conditions: continued collection of three-year follow-up data from a prospective clinical trial, and documentation of the validation of the device's cleaning, sterilization, and packaging and shipping.

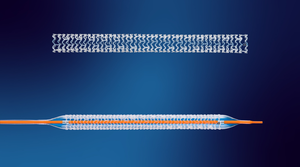

The possibility of gas embolism events during hysteroscopic surgery led Ethicon Inc. (Somerville, NJ) to issue a medical device safety alert for all lot numbers of five different Gynecare Versapoint bipolar electrosurgery electrodes and connector cables, according to the January 10 FDA Enforcement Report.

A total of 2400 electrodes and 400 handpieces were distributed nationwide. Subject to the action were the resectoscope electrode (product codes 1930, 1939, 1948, 1950, 1980, 1985); spring-tip electrode, 5 FR (product codes 0471, 0472); twizzle-tip electrode, 5 FR (product codes 0470, 0467); ball-tip electrode, 5 FR (product codes 0466, 0469); and RN-001/004-1.

James G. Dickinson is a veteran reporter on regulatory affairs in the medical device industry.

To the MDDI March 2001 table of contents | To the MDDI home page

Copyright ©2001 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like