The Impact of Comparative Effectiveness Research on Spine Care Device Companies

Recent trends in healthcare expenditures related to spine care show increasing costs and significant geographical variations in treatment patterns. These data, along with a lack of consistent success for spinal surgeries, has led to increased scrutiny of the spine care industry by payers. Expenditures associated with spine problems totaled $86 billion in 2005, an increase of 65% since 1997.

December 4, 2012

Recent trends in healthcare expenditures related to spine care show increasing costs and significant geographical variations in treatment patterns. These data, along with a lack of consistent success for spinal surgeries, has led to increased scrutiny of the spine care industry by payers. Expenditures associated with spine problems totaled $86 billion in 2005, an increase of 65% since 1997. What some consider “overtreatment” of chronic back pain has occurred through the use of imaging, opioid analgesics, spinal injections, and surgery.1 Some studies on complex procedures and devices have even found that lumbar fusion surgery for discogenic axial low back pain appears to offer only limited relative benefits over cognitive behavioral therapy and intensive rehabilitation, and that as few as 50% of fusion patients are likely to have high-quality outcomes.2

To promote lower costs and better outcomes, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), allocated $1.1 billion to Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER). The Institute of Medicine (IOM) defines CER as a comparison of the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care.3 Ideally, policymakers would like to reduce costs without impacting the quality (or the perceived quality) of healthcare, and comparative effectiveness research is seen as one way to get there, since CER takes both clinical effectiveness and cost into consideration. By replacing ineffective treatments and standards of clinical care with effective ones, or by replacing more expensive treatments and standards with equally effective, but less expensive ones, the cost of care can be brought down, in the words of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) “without adverse health consequences.”4

To promote lower costs and better outcomes, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), allocated $1.1 billion to Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER). The Institute of Medicine (IOM) defines CER as a comparison of the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care.3 Ideally, policymakers would like to reduce costs without impacting the quality (or the perceived quality) of healthcare, and comparative effectiveness research is seen as one way to get there, since CER takes both clinical effectiveness and cost into consideration. By replacing ineffective treatments and standards of clinical care with effective ones, or by replacing more expensive treatments and standards with equally effective, but less expensive ones, the cost of care can be brought down, in the words of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) “without adverse health consequences.”4

The CBO has consistently pointed to evidence in support of the idea that there are massive savings to be had by changing patterns of clinical practice.5 The evidence for this comes from several sources. First, other countries have equivalent or better outcomes with much lower costs.6 Second, an analysis of Medicare spending within the U.S. showed large variations across regions in cost per patient that were not associated with increased illness, higher payment rates, or better outcomes.7 By some estimates, total Medicare costs could be reduced by 30% if the entire country adopted the practice patterns of the most efficient regions. It has also been estimated that between 30% and 65% of all surgeries that are performed in high use regions are either clinically inappropriate or of “equivocal” value.8

For these reasons, CER findings, once established, are likely to find their way into guidelines and restrictions by payers on eligibility for procedures. Consequently, companies that make medical devices for spine care must begin to better demonstrate the value of their products for the treatment of spinal conditions, or run the risk of losing market share and even access for lack of an economic and clinical value proposition.

Comparative Effectiveness Research

It is worth noting the relationship between CER and Evidence Based Medicine (EBM). CER is similar to EBM in that both, in principle, are about providing high quality evidence. EBM focuses on use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. In contrast, CER is broader, comparing the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition and is used for individual and population level decisions.

As part of the CER funding, the IOM was commissioned to create a report outlining priority areas for CER studies. According to the IOM, “there frequently are no studies that directly compare the different available alternatives or that have examined their impacts in populations of the same age, sex, and ethnicity or with the same comorbidities as the patient. Comparative effectiveness research (CER) is designed to fill this knowledge gap.”9

The IOM report went on to identify a number of spine care issues among its top 100 priority areas for CER, after obtaining input from professional organizations and the public, as required by ARRA. The topics were divided into quartiles, with the first quartile considered the most important. Some of the spine care related issues that were among those prioritized included the following:

Establish a prospective registry to compare the effectiveness of treatment strategies for low back pain without neurological deficit or spinal deformity (First Quartile).

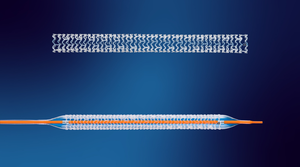

Compare the effectiveness of treatment strategies (e.g. artificial cervical discs, spinal fusion, pharmacologic treatment with physical therapy) for cervical disc and neck pain (Second Quartile).

Compare the long-term effectiveness of weight-bearing exercise and bisphosphonates in preventing hip and vertebral fractures in older women with osteopenia and/or osteoporosis (Second Quartile).

Establish a prospective registry to compare the effectiveness of surgical and non-surgical strategies for treating cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) in patients with different characteristics to delineate predictors of improved outcomes (Third Quartile).

Compare the effectiveness of traditional and newer imaging modalities (e.g. routine imaging, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], computed tomography [CT], positron emission tomography [PET] when ordered for neurological and orthopedic indications by primary care practitioners, emergency department physicians and specialists (Third Quartile).

Compare the effectiveness (e.g. pain relief, functional outcomes) of different surgical strategies for symptomatic cervical disc herniation in patients for whom appropriate nonsurgical care has failed (Fourth Quartile).

CER priorities targeted orthopedics, particularly spine, because it's so costly, and because of concerns about patient outcomes. Spine care device manufacturers will be increasingly challenged to demonstrate differential effectiveness – in terms of clinical outcomes and cost – of their devices. Without doing so, they stand to face significant restrictions in reimbursement by CMS and payers. Device manufacturers need to look to new methods of demonstrating value for payers and patients. They will need to prove benefit over existing products, and usefulness in treating spinal conditions.

Are device companies being overly aggressive in promoting their products?

CER is about the improvement of treatment protocols and comparing available products to the competition to determine which ones work best and at the lowest cost. Device manufacturers can’t simply market their products without having clear evidence that they will be effective (based on cost and outcomes) for a particular course of treatment. CER focuses on spine care because of its high cost and the frequent failure of spinal surgery to make a clinical difference to patients. As such, CER will put pressure on manufacturers to change their approach to integrating products within the new healthcare delivery model. It will be essential that they ensure appropriate use of their devices, rather than simply pushing new technology.

Specifically, the healthcare delivery industry can expect to feel significant pressure from CER in two particular areas. The first of these will be in the development of predictive care paths. These will identify what treatment protocols work best, including the value of certain devices and procedures. Once these specific treatment patterns become the standard, they will

a) be adopted by most private insurers.

b) be adopted by physicians themselves as the default standard of treatment.

These care paths are certain to impact the projected priority areas earliest and most strongly, which has implications for spine care.

The second consequence of CER for the delivery industry will be changing quality metrics. Traditional methods (measuring mortality and morbidity) will be replaced by a combination of process metrics (compliance with guidelines) and outcome metrics that integrate quality of life into traditional measures. This will take place as part of the shift from a focus on clinical effectiveness to a focus on cost effectiveness, because cost effectiveness is nearly universally defined to include quality of life (e.g. the QALY, or quality-adjusted life year).

In addition, just demonstrating that a product works and is cost-effective may not be enough. This is why manufacturers need to additionally focus on showing the value of a product within the context of care paths, and as such, may need to help doctors improve their diagnostic specificity. It’s about making sure a patient receives the right treatment with the right product at the right time… to achieve the right outcome. A 50% failure rate is a damning statistic. If your device is part of a surgical treatment that can’t claim a better success rate than a coin flip, your product will not be identified as a viable option.

Changing perceptions of value suggest that manufacturers will need to provide evidence on the appropriate use of their devices, and outcomes data that demonstrates effectiveness – not just data demonstrating product capabilities. If manufacturers just stand by and leave CER to the researchers, HHS will eventually restrict use of devices based on its research, and manufacturers will have lost their opportunity for meaningful input, at significant cost. Additionally, in the context of growing healthcare consolidation, manufacturers will need to prove their product value to purchasing organizations or rely purely on price concessions to retain access in the face of vendor consolidation. The choice for manufacturers it to take the initiative now, or risk losing market position and market access later.

The Next Steps

Philosophically, NAI advocates taking steps to try and shape the future, especially the regulatory environment. Consequently, we recommend that manufacturers partner with providers and fund research to gather acute and post-acute care data as a basis for improving diagnostic accuracy. Use of registries combined with longitudinal follow ups can yield the kind of data that will make this possible. This includes capturing information about products, techniques, comorbidities, etc. A good model for this can be found in cardiology. The registry maintained by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons captures critical acute care data. If this could be combined with longitudinal follow-up data it could provide a wealth of meaningful information about implant functionality and much more.

There are also business development opportunities in integrating services with products to enhance both (like physical therapy). Medical device companies could also partner with hospitals/systems/clinics that do surgeries. The important thing is to give providers a compelling argument demonstrating outcomes in terms of safety, efficacy, and cost to improve reimbursement.

Providers have an interest in being able to demonstrate the value of their own clinical work and so should be willing partners in the enterprise. As a bonus, it may open doors to opportunities for a service wrap approach for manufacturers that could enhance the brand and create new revenue streams.

Spine care will remain a priority of CER given the current variation in outcomes and treatment patterns, and that current evidence indicates higher surgery rates (with higher costs) do not necessarily demonstrate better outcomes, and sometimes demonstrate worse outcomes. CER establishes the reason for using a product or treatment protocol. Registries or longitudinal research is the action that manufacturers/providers can take to establish value. The purpose of all this is to sharpen diagnostic accuracy and defend against more restrictive action by CMS and private payers. Such investments now can be the key to your future bottom line.

References

Manchikanti L, et al. "Facts, fallacies, and politics of comparative effectiveness research: Part I.," Pain Physician Journal, 2010.

Carragee EJ. "The role of surgery in low back pain," Current Orthopaedics 21, no. 1 (2007): 9–16.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). "Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research," (The National Academies Press, Washington, DC: 2009): 13.

Congressional Budget Office, Research on the Comparative Effectiveness of Medical Treatments. December, 2007.

Congressional Budget Office, World Health Organization The World Health Report 2000. June, 2000.

Voelker R. "US Health Care System Earns Poor Marks," Journal of the American Medical Association 300; no. 24 (December 24, 2008): 2843.

Dartmouth Atlas Project, Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care, cited in Research on the Comparative Effectiveness of Medical Treatments.

Chassin MR, Kosecoff J, Park RE, et al. Does Inappropriate Use Explain Geographic Variation in the Use of Health Care Services? A Study of Three Procedures. JAMA. November 13, 1987. vol. 258; no. 18: pp. 2533-2537.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2009. p. 1.

+++++++++++++

Rita E. Numerof, Ph.D. is President of Numerof & Associates, Inc. (NAI). NAI is a strategic management consulting firm focused on organizations in dynamic, rapidly changing industries. We bring a unique cross-disciplinary approach to a broad range of engagements designed to sharpen strategic focus, increase revenues, reduce costs, and enhance customer value. For more information, contact NAI via email at [email protected] or by phone 314-997-1587.

Rita E. Numerof, Ph.D. is President of Numerof & Associates, Inc. (NAI). NAI is a strategic management consulting firm focused on organizations in dynamic, rapidly changing industries. We bring a unique cross-disciplinary approach to a broad range of engagements designed to sharpen strategic focus, increase revenues, reduce costs, and enhance customer value. For more information, contact NAI via email at [email protected] or by phone 314-997-1587.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like