Everything You Need to Know about UDIs

When FDA publishes its final rule on Unique Device Identification (UDI), which should be any time now, medical device companies will face a daunting new obligation on their list of prescribed regulatory compliance activities. Device manufacturers must keep calm and plan ahead. There are active steps companies can take now to gain improved clarity on the key requirements related to UDI, and to prepare more effectively for the implementation of the final rule.

June 26, 2013

Ready, Set, ... UDI

The medical device industry has begun the race toward UDI. In March of 2012, FDA published its long-awaited Draft Rule on Unique Device Identification, collected public and industry comments, and is now gearing up to release its final rule. The proposed rule (and the amendment issued in November of 2012) gives us a good idea of what will eventually be required.

For its part, the European Commission has released its own initial guidance recommendation “…on a common framework for a Unique Device Identification System” in early April of 2013. It is clear that a challenging set of global regulatory requirements is on its way.

For device companies, UDI compliance will not be a small initiative, nor will it be a simple one. Whether an organization needs to bring 10 or 10,000 SKUs into compliance, now is the time to prepare.

UDI Primer

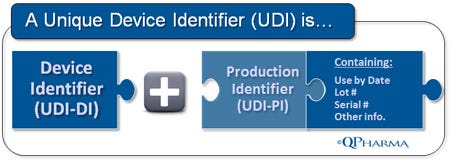

If you are new to the concept of UDI, it can seem like a bit of alphabet soup. Here is a brief primer on the key components (based on the FDA draft rule).

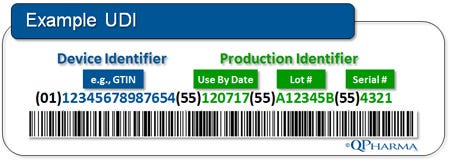

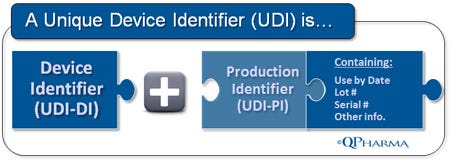

UDI Device Identifier (UDI-DI). UDI-DI is the static component of the UDI. It is an entirely new entity created by the UDI regulation for the “unambiguous identification” of medical devices used in the United States. The UDI-DI will be a fixed, ISO-based code for item identification (for example, GTIN from GS1).

UDI Production Identifier (UDI-PI). UDI-PI is the “dynamic (or variable) component of the UDI. It contains specific and accurate production information, including the “Use By Date,” the lot/batch number, and the serial number, if applicable. The information required in the UDI-PI has been part of product labeling requirements for years per 21 CFR 820, and should, for the most part, be usable as-is.

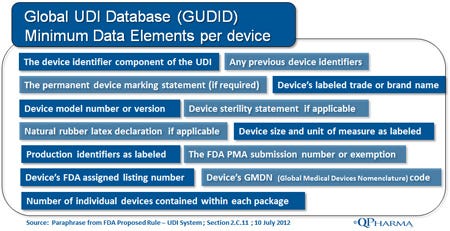

Global UDI Database (GUDID). GUDID will be the master database that will serve as the publicly accessible nexus of information related to approved medical devices. For medical devices, the GUDID will function in much the same as the NDC Directory does for pharmaceutical products. FDA has completed the compilation of the database, and publication of the final GUDID user guide is expected in the same timeframe as the Final UDI Rule. There are many open questions about the GUDID, but in general we have a good idea of what the initial required data fields will be, and that eventually the database will be set up for public access. The illustration here shows what is expected to be the required minimum data elements for each device:

There are still open questions about the GUDID related to governance, and as to how the GUDID datasets will be shared with other regulatory bodies, but the overarching goal is to make consistent information about a specific device available across international markets.

Automatic Identification/Data Capture (AIDC). The proposed FDA UDI rule will require a human-readable label and the use of at least one AIDC technology to carry the new standardized identifier on all non-exempt devices and/or their packages. In the proposed rule, FDA avoided being proscriptive about the specifics of which AIDC technology to be used, and industry will have some latitude here. AIDC options include linear and 2D barcodes, and RFID tags (the most common at present).

More exotic options for AIDC, such as Near Field NFC and Bokodes, may eventually emerge as standards as well. (Side note: Bokodes are a next generation label developed byMIT’s Media Lab designed to pack multiples of data volume on a label the same size as or smaller than today's bar codes. This is accomplished by variable focal distances of data or “Bokeh.” The Bokode prototypes may also provide enhanced security versus RFID tags, and a further scan distance compared to today’s bar code scanners.)

However, it may be wiser to stay with linear and 2-D barcodes in the near term, as most stakeholders already have the scanning tools for these labels in place. Scanning systems are costly, and it would be wise to use established standards for the present until a clear and globally accepted next-generation standard emerges.

What We Know about the Coming Final Rule

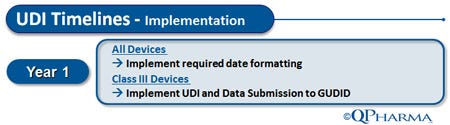

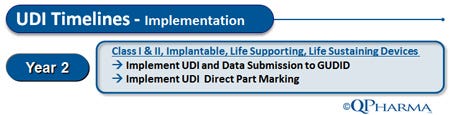

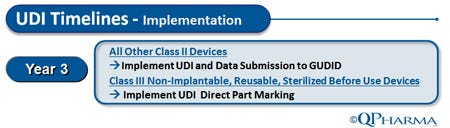

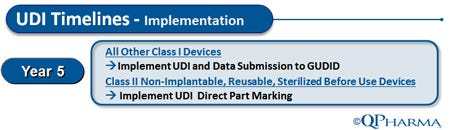

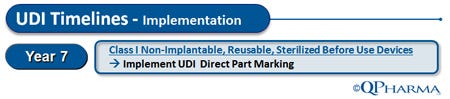

The good news is that dates for implementation of requirements will be phased, with higher-risk devices given priority. During the comment period after the release of the proposed UDI rule, FDA received extensive feedback from industry about implementation timelines. The following is a high-level overview of the UDI Implementation timelines as per the amended proposed rule.

Year One. 12 months from the issuance of the final rule, medical device manufacturers must ensure that all dates on device labels align with the rules in the format specified in § 801.18: MMM DD, YYYY (e.g., SEP 30, 2012). Perhaps most daunting to industry is that also by that date, all Class III devices must be labeled with a UDI and have the related data submitted to the GUDID. FDA has acknowledged that this is an aggressive time requirement for Class III devices, but extension of this deadline does not seem likely.

Year Two. 24 months from the issuance of the final rule, medical device manufacturers must ensure that all Class I and II implantable, life-supporting, and life-sustaining devices carry a UDI and have their related data submitted to GUDID. Further, all implantable devices must have direct part marking. For many devices, the requirement for direct part marking will be an almost herculean task and may require extensive device redesign and even reengineering to ensure that the codes fit and will endure after implant.

Year Three. 36 months from the issuance of the final rule, nonimplantable, reusable, or sterilize-before-use Class III devices will be required to have direct part marking. Also included in the UDI requirement at the three-year mark are stand-alone software products that are regulated as medical devices. The software question is an interesting one, because there is not yet clarity from the agency as to how UDI labeling will be handled for downloadable (yet regulated) software. In the not-too-distant future, software applications being downloaded to a doctor’s or other care provider’s tablet for use with patients will probably be a routine occurrence, and there will need to be some clear guidance as to how UDI will be applied to these digital products.

Year Five. The timeline in the amended draft rule is risk based, with a goal that the devices with the highest overall risk are required to bear UDIs soonest. By year five, all remaining Class I devices are required to have UDIs and GUDID data submitted. The remaining Class IIs (nonimplantable, reusable, and/or sterilize-before-use devices) will be required to have direct part marking. Hopefully, by 60 months out from the final rule, most medical device manufacturers will have had ample time to resolve the challenges of direct part marking.

Year Seven. The longest implementation time deadline for UDI as stated in the draft rule is seven years for direct part marking of Class I non-implantable, reusable, or sterilize-before-use devices. Year Seven is the final timeline milestone, and the reason the last deadline is lengthy is to give reasonable leeway to Class I medical device makers who may be significantly smaller than the manufacturers of the more complex Class III and II devices.

Labeling Standards. Along with the timelines for implementation, device firms must decide on the labeling standard it will use. In the draft rule, FDA specifically avoided proscribing the standard for labeling that must be used, and device manufacturers will have to make a choice as to which standard makes the most sense for their organization.

At present, there are several labeling standard options to consider, as FDA has left much latitude for choosing standards. When reviewing the three of these standards it is important to understand the benefits and drawbacks of each standard before making an organizational commitment.

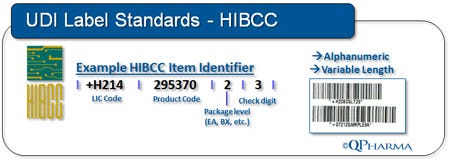

HIBCC (Health Industry for Business Communication Council). Historically, the medical device industry has used HIBCC UPNs (Universal Product Numbers), and the supply chain and supporting systems of many device manufacturers have been built using HIBCC codes. Positives to consider include the fact that HIBCC codes are alphanumeric and up to 18 characters in length. They generally have a smaller label footprint as compared to the GS1 option. At present, HIBCC requires a one-time fee scaled against gross sales with no annual recurring fees — a benefit for small device manufacturers. One of the drawbacks of HIBCC is the perception that it is primarily U.S.-focused and less global than other options.

GS1 (Global Standard 1). Historically, the pharmaceutical industry has used GS1 (previously known for its inception of UCC codes in the USA and EAN codes in Europe globally.) In the early 2000s, the UCC and EAN teams joined forces and consolidated their offerings under the GS1 banner worldwide. GS1 has been steadily gaining momentum, and is generally thought to be more global in focus than HIBCC. Distributors, many of whom have international presence, favor GS1 and have been putting pressure on manufacturers to carry GS1 codes. Furthermore, a number of national regulatory bodies have mandated that products sold in their nations carry GS1 codes. The UK, Japan, Spain, India, and Australia all require GS1, or will in the near future. However, GS1 codes are expensive to acquire and require yearly renewal fees. Many device makers have felt “strong-armed” into transferring to GS1.

ISBT 128 (International Standard for Blood and Transplant). ISBT 128 is a third possible labeling standard for UDI, and is broadly used in the blood and blood products industry. The “128” reflects the 128 characters of the ISO/IEC 646 7-bit character set. ISBT 128 is very specific to (and highly suited for) the specific needs of the blood products, tissue, and transplant community. Whether ISBT128 codes will gain traction outside of those specific markets remains to be seen.

What We Don't Know about the Coming Final Rule

Inventory Consignment Stock. As the UDI rule is implemented, some have asked whether it will allow the sale of existing stock without UDI. It might be that firms will be required to rework and label existing stock with the new codes, but the answer is unclear. This is a serious question that has many device manufacturers worried. Some hope might be gleaned from precedent set with the pharmaceutical industry, which was allowed a two-year cut-over period to sell out existing stock at the inception of requirements around item-level NDC codes. It is reasonable to assume a chance for similar leeway for UDI.

Retail Exemption. Another open question is whether there will be any sort of flexibility for retail medical device products. At present, almost all retail products in the United States and many other markets carry Universal Product Codes (UPC). As explained above, UDI will require two components: the UDI-DI, which can be captured by retail scanners using the UPC standard and the UDI-PI, which cannot be captured by current UPC scanners and systems. Makers of retail medical devices have asked the FDA for leeway—the final rule should address the question clearly.

First Steps for Medical Device Companies

As stated previously, maintaining UDI compliance will clearly not be a simple effort, and now is the time to plan. There are some smart steps manufacturers can take to begin preparing:

Identify new UDI requirements that are likely to apply to your organization. Appoint a UDI champion in the organization, and have that person serve as the key resource and clearinghouse for the latest news and rules related to UDI. Empower this individual and his or her team to attend conferences and workshops related to UDI, and give them the budget and authority necessary to identify and bring in external professional resources to assist in the transition to UDI compliance.

Conduct an “As-Is” analysis to see where UDI rule will affect your organization. Once the UDI champion has been identified, their first step should be to evaluate things as they are at present: Develop a concise understanding of what labeling standards are in place; and Identify the flexibility and limitations of existing labeling and supporting technologies.

Survey customers to determine expectations for UDI. After getting an accurate “As-Is” picture of the organization’s labeling standard landscape, the UDI champion should engage formally with customers to understand their expectations and concerns regarding UDI — especially as it relates to label standards. Distributors have taken the lead in this area, and many have settled on a specific standard. They may require that manufacturers be able to supply products labeled in accordance with that standard.

Survey vendors to determine their capabilities for UDI. In parallel with surveying customers about their expectations, it is important to have a similar “upstream” dialogue with vendors to determine the UDI-related formats in which they will supply parts and other components.

Do a “Should-Be” analysis to determine what needs to change, and identify gaps. After formal discussions with customers and vendors, and after having conducted an accurate “As-Is” analysis of current UDI capabilities, UDI champions should consider all inputs and come up with a logical “Should-Be” plan to prepare for UDI requirements on all fronts. This is a vital step, and it may be wise to engage external consulting resources to help not only identify a coherent and cost-effective path forward, but also to ensure that sufficient resources are in place to execute against plans.

Identify a pilot project to fill an identified gap in the UDI implementation plan. This is the best way to get started — and to begin building organizational awareness and strong momentum toward full UDI compliance.

Remember, UDI will not be optional, and compliance will soon be a business imperative. Planning ahead, identifying internal champions, and making proactive decisions based on the information currently available are the best ways to ensure that your organization is fully and capably prepared.

Acknowledgement: The author would like to thank Brendan Middleton and Alberta Burman of QPharma, Inc. for their editorial contributions.

Tom Beatty leads the UDI compliance practice for QPharma, Inc. He has more than 18 years of life sciences market and project experience, and is a graduate of the University of Notre Dame.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like