Beyond Product Development: Creating a Process That Drives Innovation

Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry MagazineMDDI Article IndexOriginally Published November 2000Product Development Moving efficiently and effectively from idea to finished product requires medical device manufacturers to integrate concept, technology, and product development strategies into every phase of their operation.Thomas J. Lenk, Aritomo Shinozaki, and Christina Hepner Brodie

November 1, 2000

Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry Magazine

MDDI Article Index

Originally Published November 2000

Product Development

Moving efficiently and effectively from idea to finished product requires medical device manufacturers to integrate concept, technology, and product development strategies into every phase of their operation.

Thomas J. Lenk, Aritomo Shinozaki, and Christina Hepner Brodie

Often, when manufacturers try to do something technically different with their product design, development schedules start to slip almost uncontrollably. Some projects end up being abandoned completely due to technical problems after significant time investments have been made by R&D, marketing, and production personnel.

How can manufacturers embark on technically challenging projects without bogging down their entire system? How can they ensure that their product development process is not only efficient, but also effective in producing successful, innovative products?

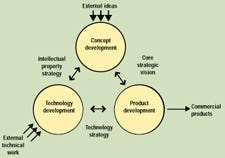

The first step is to stand back and look at what's required. There are really three processes involved in going from idea to product: concept development, technology development, and product development. The interrelationship of these three processes and their supporting frameworks is shown schematically in Figure 1. None of these processes exists in isolation—some ideas feed directly into product development, while others require technical development to be feasible. Technology development provides solid technologies for incorporation into the product development process, and it also spurs new ideas. The product development process itself may even generate new concepts or illustrate the need for new technology. The key to consistently developing successful, innovative medical devices is to understand the unique characteristics of all three of these processes and then manage them appropriately. The processes must be adapted to a company's specific business environment and supported with the use of complementary tools and a compatible infrastructure.

Figure 1. Schematic of the three processes involved in going from idea to product.

Figure 1. Schematic of the three processes involved in going from idea to product.

This article looks individually at the most important contributors to a strong concept-to-product process. It starts with strategy, then briefly reviews the requirements of an effective product development process before discussing tools to help manage technology and concept development. Finally, it examines how everything fits together to take manufacturers from idea to product.

STRATEGY SETTING

The first step for a design team is to decide where it wants to go. Strategies are set at many different levels, from the overall direction (the core strategic vision), to the role of new technology (technology strategy), to how new concepts will be protected (intellectual property strategy). It is important to remember that a strategy is not an end in itself; the value of strategy comes from its use in guiding and coordinating decision making across functions and levels of an organization.

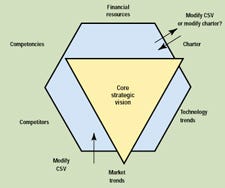

Core Strategic Vision. The core strategic vision (CSV) is the cornerstone for all other strategy and decision making. A good CSV will answer three questions very clearly: Where is the company going? How will it get there? Why will it be successful? The CSV is a structured framework for strategic thinking. It is not just a set of goals, but is shaped and tempered by both internal capabilities and external factors. The CSV and the internal and external boundaries are shown schematically in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Schematic of the core strategic vision and internal and external factors.

Figure 2. Schematic of the core strategic vision and internal and external factors.

External factors that define what is worth pursuing include market trends (what do the customers need and what do they expect?), the state and advancement of the new technologies, and the actions and capabilities of competitors. These three factors define the opportunities for success in the marketplace.

Three internal factors further contribute to the CSV: the firm's competencies, its financial resources, and its charter. If there is a conflict with the external factors, the CSV must be amended accordingly. If there is a conflict with one of the internal factors, the first question to answer is whether it is possible to change the constraint to fit the CSV. If it is, a decision must be made: Is the proposed CSV compelling enough to justify the change, or should the CSV be molded to fit the internal constraint? For example, a company may discover a path that fits wonderfully with external factors but that requires competencies beyond what the company originally envisioned. Should the path be rejected as outside the boundaries of the CSV, or is the opportunity worth the risk and effort of changing the CSV's limits? Bringing the CSV into alignment with the external limits makes it realistic; aligning it with internal capabilities makes it achievable.

Technology Strategy. The technology strategy goes a step further than the CSV and sets the direction for technology development. Without a clear technology strategy, development projects may not align with product strategy, leading to wasted development efforts or unsuccessful technology transfer attempts. A best-practice technology strategy will use the concept of technology platforms to enhance product platform planning, to drive innovation into new product categories, and to tie new basic research findings into technologies of interest. A good technology strategy answers the following four questions:

Which technologies are needed to support current product platforms?

Which technologies must be developed to support or enable new product platforms?

What is the potential of these technologies?

How can the company develop or acquire the necessary technologies?

The technology strategy should support the product strategy, but may extend beyond it. It is very likely that the technology strategy will suggest the need for technologies that don't exist—clear targets for innovation. The directed ideation process described below can be used to generate concept development in these target areas.

Intellectual Property Strategy. To get the greatest benefit from investments in concept and technology development, it is essential to understand how to manage the resulting intellectual property (IP). At the core of IP management is the choice of IP strategy. There are several options, each with its own benefits and constraints. They can be summarized roughly as follows:

Exclusionary Enforcement. Companies maintain competitive advantage by denying access to technology and patents. This is a common mode of operation in the medical device industry, where high development and testing costs require a high return on an investment in new technology.

Return on Investment. Balancing internal-use and licensing agreements can generate additional revenues beyond product sales. Tracking of agreements often results in greater IP management costs, however, and there must be a clear technology strategy to guide which technologies are suitable for licensing and which should be retained exclusively.

Freedom of Action. Broad cross-licensing results in high product design flexibility by providing access to a broad range of technologies, but it comes in exchange for a lower ability to exploit technological superiority. This can be effective in high-volume industries where a firm can exploit manufacturing and design engineering expertise.

Benign Neglect. Benign neglect results when there is no effort toward cross-licensing or patent enforcement. This usually leads to fast time to market and low IP management costs, albeit with higher risk and lost opportunities for maximizing technology benefits. It is most suitable for technologies that are easily innovated around or otherwise difficult to defend.

Successful companies view IP as a source of potential profit and competitive advantage. These companies ensure that IP strategy is aligned with their corporate, business, and technology strategies. IP strategy is often integrated into the early stages of technology development to shape research strategies and to guide licensing negotiations and collaborative research arrangements.

A firm that has a clear picture of its strategy is also in a better position to make good decisions when screening concepts. Ideas worth pursuing for further development and possible patenting under a cross-licensing strategy may not have the same appeal if a company feels that exclusionary enforcement is the correct path to follow.

PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

The benefits of managing strong front-end processes in concept and technology development are lost without a good product development process to bring new ideas and technologies to commercialization.

To consistently develop new concepts and technologies into successful products, a firm should focus first on product development project excellence. Project excellence consists of the following four key elements:

Core Teams. A cross-functional team should be formed to focus on a project and empowered to deliver results. Both the team's authority and the expected results must be clearly defined.

Structured Development Process. A common framework should be designed to guide repeatable product development activities. Deliverables should be clearly defined, activities should be grouped into distinct phases, and the project should be reviewed at the completion of each phase. By grouping the activities properly, it is also possible to coordinate the phases with the completion of requirements for design control reviews.

Decision-Making Reviews and Process. A senior management product approval committee should review projects at the completion of each phase of product development. Both project progress and business potential must be evaluated. The project team receives a crisp decision of go (continue the project to the end of the next phase), no go (end the project), or redirect (change the goals and scope of the project).

Development Tools and Techniques. Working tools like checklists and templates for standard communications should be provided so that teams can focus their energy on project progress and the content—rather than the format—of reports and presentations. Clear metrics, such as due-date slippage or turnover on core teams, allow the process to be monitored for early detection and correction of problems.

A good product development process involves a set of relatively well-understood activities, done in a specific order, with clear checkpoints to allow evaluation of progress and continuing potential. Without project excellence, technology transfer can stumble into an unrepeatable and uncertain set of product development activities. The benefits of a clear and well-defined technology development process will be lost if the product development process is unable to maintain the time-to-market schedule or other product advantages.

| Product Development | Technology Development |

Goal | Commercial product | Enabling technology |

Timing | Can be reasonably estimated | Uncertain |

Activities | Well-defined set; most will be repeated for all projects | Often undefined, may be new and unique experiments |

Management | Coordinating common-goal disperse activities | Reducing uncertainty |

Table I. The differences between product development and technology development.

Technical Performance Criteria | Ultimate Performance Goal | Technology Feasibility Points | Confidence Level |

Compound swelling triggered by low alcohol concentration | 1–2% w/v EtOH in aqueous base | At least 10% volume expansion on 2-minute exposure to 3% v/v EtOH and water | 50% |

Compound swelling not reversible | No shrinking once full expansion obtained | Less than 20% shrinkage 3 hours after full expansion achieved, tested at 35°C | 10% |

Compound not a skin irritant | No skin sensitivity in either humans or animals | No skin sensitivity demonstrated in rats upon skin attachment for a period of 2 weeks | 70% |

Table II. A sample technology development matrix.

TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT

In the medical device industry, new technologies are constantly needed to feed a strong product development process. Technology development is the process of taking an idea and making it usable in a commercial product. While technology development is similar to product development in many respects, there are some important differences. These are described in more detail in Table I, but can be summarized in one key point: technology development involves more uncertainty than does product development, both in the ultimate goals and in the activities required to reach them. Reducing this uncertainty or risk is a primary focus of technology development. Two tools are useful to manage uncertainty and to direct the project more quickly to a useful end: the technology development matrix (TDM) and the timed-phase review process.

The Technology Development Matrix. Correctly applied, a TDM serves several purposes: it defines the boundaries of the required solution, it focuses effort on the most critical aspects of the problem, and it provides a vehicle for measuring progress.

A sample TDM is shown in Table II. The information in each column of the table has a specific role in guiding technology development. The first column consists of technical performance criteria. These criteria are required for an effective solution to the problem being addressed. They should provide a general, complete, and nonconflicting picture of what the technology will be expected to do, but not how it will do it. These are not technical specifications; they are technical requirements to meet market needs or to ensure compatibility with other technologies or platforms. These criteria define the project, and should be developed collaboratively by marketing and engineering personnel. Time spent on this part of the TDM will be quickly repaid in time savings on the project and in avoiding solutions that are desirable but not practicable.

The second column of Table II contains the ultimate performance goals. This is the level of performance that would be expected for a commercial product to succeed in the marketplace at the time a product using the technology is expected to be launched. Again, these goals should be developed collaboratively by marketing and engineering.

The third column of Table II contains technology feasibility points (TFPs). These are measurable benchmarks that define when the technology is ready for transfer into the product development process. They should be defined in specific, measurable terms, so the development team has clear targets for their efforts and clear goals to measure themselves against. Depending on the amount of development risk that the company is willing to carry in the product development process, these technology feasibility points may be close to or considerably below the ultimate performance criteria. For technologies going into a product development program requiring sizable preclinical tests, the TFPs for performance criteria most likely to have a substantive effect on trial results should be quite stringent.

The last column of the TDM in Table II is the confidence level for each technology feasibility point. The confidence levels serve three purposes. First, they help direct effort on the project. Low confidence levels quickly indicate which areas are in the most need of additional work—and clearly identify potential project killers. Second, the confidence levels provide a means of measuring progress. Finally, using the confidence levels with the TDM provides a quick and clear method of communicating the project's goals, progress, and areas of concern—even to those unfamiliar with the details of the project.

Time-Limited Phase Review Process. The phase review process for project evaluation and approval plays a valuable role in both product development and technology development. The uncertainty inherent in technology development, however, can add a new wrinkle to the process, and using milestone-based reviews is often inadequate. The solution is to establish a review process using both activity-based and time-based checkpoints. If specific technical milestones that require decisions on project direction are reached within a set time frame, the project is reviewed when the milestones are reached. If the project reaches the time limit without achieving the milestones, the project is still reviewed for technical viability and direction. This practice provides direction at key milestones and also ensures that a project won't founder if a milestone is unachievable.

Reviews need to address both the technical feasibility and the business justification of a project. Few people in any organization are competent to review both effectively, however. The solution is to establish two types of reviews—technical reviews and business reviews. The purpose of technical reviews is to assess technical progress and direction, and the reviewers should be technical experts. The validity of the results is reviewed, the project is determined to be either acceptable or unacceptable on technical grounds, and plans for future work are approved or amended based on technical measures and goals.

The purpose of the business review is to ensure that the end product still makes business sense. Markets change, strategic visions change, and technical projects evolve as understanding increases—and periodic review for business fit helps ensure that project goals and business requirements stay in alignment. Business reviews should follow shortly after technical reviews so that the project's technical feasibility and direction are clear before trying to evaluate its business significance. Business reviews will often be less frequent than technical reviews, especially in the early stages of a technology development project, but should always follow the achievement of major technical milestones where decisions on project direction need to be made.

CONCEPT DEVELOPMENT

Concept development is the fountain that feeds both technology development and product development. Harvesting ideas for the purpose of product development requires a mechanism for routinely capturing, organizing, developing, and screening ideas. Concept development can be approached in two ways: routine ideation, making effective use of the ideas that occur spontaneously in the organization, and directed ideation, using tools and techniques to spur idea generation on a focused issue. Both have important roles in driving innovation.

Routine ideation takes advantage of breadth and volume—a wide diversity of avenues and individuals are involved and a large number of ideas are captured and managed. Relatively little effort is expended on any given idea, with little expectation that any one idea will be truly innovative or ultimately successful. Keys to success in this approach include ease of use and effective downstream screening, relying on technology and development processes that truly "gate" further development.

Directed ideation relies on focus and depth—small, select teams of people working to understand detailed needs relative to a chosen topic. Significant effort is expended on each idea, with a much higher expectation that those ideas will be innovative and successful. Keys to success in this approach include the use of sophisticated tools and techniques specifically designed for strategic analysis and idea generation and evaluation.

Routine Ideation: Idea Collection and Screening. For medical manufacturers, there is a wealth of potential idea sources that could lead to product improvements or new product concepts. Sales personnel routinely interact with customers; applications specialists, service technicians, and call-center operators continuously interface with customers as part of their jobs; engineers and marketers may find themselves troubleshooting or visiting customers. If these people are trained to identify the problems they see and to listen for opportunities, then useful ideas will be generated. Outside inventors and creative thinkers within the company may also spark ideas that can be added to the pool. To mine this ready source, the firm's system must be designed to facilitate documenting and screening of ideas.

Some of the major requirements for an effective system are that it is easily accessible, that it has a well-defined screening process run by a small cross-functional team, that it provides acknowledgement to all contributors, and that it recognizes and rewards people who submit promising ideas.

Directed Ideation: Voice of the Customer. The concept sounds easy enough. Team members go out and talk to customers, using what the customers say to better understand a new product's requirements. To productively obtain, analyze, and act on the voice of the customer, however, a company must put together the right team and follow the right approach.

A voice-of-the-customer team should consist of a cross section of personnel from the key functions that are responsible for defining, developing, marketing, selling, and servicing a product. Since the members of the project team carry on direct discussions with the customers, it is each team member's frame of reference—built from years of experience in a given company or industry—that allows him or her to listen in a distinctive and penetrating way. It is the combination of what the interviewer and the interviewee bring to the discussion that determines the value of the interview content.

A disciplined voice-of-the customer approach must adhere to a multistep process:

Frame the Boundaries of the Project. Successful voice-of-the-customer projects have clear goals and follow a clear approach. The project team articulates the project's overall purpose, the objectives for learning from customers, and the rationale for selecting each customer to be interviewed. Team members create a common interview guide reflecting the information they hope to collect from the customers, but also understand that conversations might take unexpected turns and yield unexpected insights. They consciously stay open to such opportunities.

Create a Customer Profile Matrix. A perennial danger in customer interviews is obtaining an incomplete or misrepresentative sample of perspectives. This danger can be minimized by generating a customer profile matrix. To create such a matrix, the team first segments customer groups along traditional lines, such as medical condition, geography, or provider type. The next step is to do the opposite: examine nontraditional but relevant ways of segmenting customers, such as lead users, happy customers, lost customers, dissatisfied customers, or even noncustomers. The combination of traditional and nontraditional segments forms a framework for identifying a good cross section of customer perspectives.

Collect the Voices. The next step is to observe and interview customers in the environment in which the potential product will be used. Interview teams typically consist of two individuals with different functional backgrounds. Each team member should participate in a sufficient number of interviews to gain his or her own 360-degree perspective of the customers' viewpoint. Where permission can be obtained, tape-recorded interviews allow for a richer distillation of the customers' voices.

Use Language-Processing Tools to Gain Insights. After the interviews are completed, team members work with the transcripts from the interviews in which they participated. The nature of working with language data is such that any word or phrase—any voice or image—can be susceptible to multiple interpretations. Language-processing tools provide a structured process to help participants "think in common" about what they have observed, heard, and read. By articulating the connections they discover in more abstract terms, the team can collectively comprehend the connections and form a hypothesis based on their insight. The quality of the result will depend on the discipline and rigor of the group.

The group first uses language processing to understand the environment in which their product will be used and to discover the opportunities that exist for product or service use. They then return to the transcripts to identify and translate voices that lead to their customer requirements. Once they have identified the key customer requirements, the group may again use language-processing tools to gain insight into the set of requirements.

Define Metrics. It is important to identify how the team intends to measure—from a customer perspective—how well it meets its customer requirements. Defining the metrics prior to concept development prevents biasing the metrics toward favored concepts.

Generate Ideas and Concepts. Next, all of the team members participate in generating ideas that solve customer requirements. These ideas are used as a basis for creating total product and service concepts.

Screen and Validate the Concepts. Teams usually screen their concepts using customer requirements and performance targets as evaluation criteria. Teams can develop a broader view of the best opportunities by also screening competitive solutions and considering the relative importance of the requirements to their various customer segments. Traditional market research tools, such as focus groups or conjoint analysis, can be used to validate and further refine the team's final concept.

CONCLUSION

Despite careful planning, moving from idea to product— fitting the strategy to a viable technology that ultimately becomes the basis for a product—is extremely complicated. Ideas might be generated by products, strategies can change in response to a new technology developed inside or outside the firm, and ideas may be partially developed and dropped, just to name a few common scenarios.

Nevertheless, it is useful to look at the four pieces of the puzzle in going from idea to product: strategy setting, concept development, technology development, and product development. While there are complicated interrelationships and overlaps, each component has unique requirements. Tools such as the TDM for guiding technology development and the voice-of-the-customer approach for directing concept development help in managing these processes effectively.

Well-managed front-end processes will feed the product development process the ideas and technologies needed to generate successful commercial products. The degree of sophistication required, however, varies with the size and complexity of the organization. Large companies benefit from well-defined processes in all four areas, while smaller companies may get by with only a clear strategic vision. A medical technology start-up may only need a clear vision and a structure for its product development efforts. Even in such cases, however, recognizing which efforts are concept development, which are technology development, and which are product development—and realizing that the processes need to be managed differently—enables a team to more quickly reach the final goal of a successful commercial product.

All of the authors are consultants with PRTM. At the consultancy's Mountain View, CA, location, Thomas J. Lenk focuses on product and technology development in life science companies and Aritomo Shinozaki consults on product development and technology management for the computer and electronic industries. Christina Hepner Brodie is based in the Waltham, MA, office, where she uses voice-of-the-customer techniques to solve strategic and product related problems.

Copyright ©2000 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)