Squashing the 'Superbug' Could Start with OEMs

November 1, 2007

Originally Published MPMN November 2007

EDITOR'S PAGE

Squashing the 'Superbug' Could Start with OEMs

|

Dubbed the ‘Superbug,’ methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has managed to fly under the public’s radar for years. However, the recent death of a Virginia teen from the antibiotic-resistant bacteria has thrust MRSA into the limelight. And the public wants it exterminated.

Public scrutiny has the potential to serve as a catalyst for change. Outrage and concern could translate into increased research and funding toward MRSA studies. Scientists and specialists undoubtedly will lend their expertise toward developing drugs that thwart the bacterial foe. But it may be device manufacturers that make an early difference.

MRSA is the result of a vicious evolutionary cycle. Praised as one of the most important inventions of the 20th century, penicillin revolutionized healthcare. Unfortunately, overuse of the drug led to a mutation of bacterial strains that rendered them immune to the antibiotic. Methicillin was then created as an alternative; however, the cycle repeated itself as MRSA emerged.

Although not confined to healthcare settings, MRSA has long been to blame for hospital-acquired infections (HAIs). In fact, a study published in the October 17 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association states that an estimated 27% of MRSA infections were healthcare-associated.

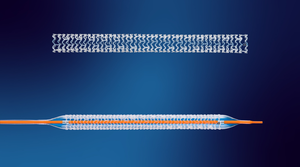

A significant portion of these HAIs can be attributed to lax hand washing by medical professionals coupled with the vulnerable immune systems of patients. But biofilm formation on indwelling devices, such as catheters, is responsible for a host of blood stream and other MRSA-related infections as well.

That’s where OEMs may be able to help. Without a targeted MRSA treatment, the first line of patient defense against MRSA-caused infections lies in medical device design.

Mitigation of biofilm formation on a device can be achieved by the addition of protective coatings, for example. Companies such as AcryMed (Beaverton, OR) and Covalon (Mississauga, ON, Canada) have already begun exploring the possibilities in this field, harnessing the antimicrobial properties of silver for use in coatings.

AcryMed developed SilvaGard surface-engineered antimicrobial treatment to block biofilm formation on devices such as catheters and pacemakers. Covalon’s technology consists of applying a covalently bonded hydrophilic polymer coating to a device. It enables the delivery of silver ions from the device surface, creating an antimicrobial surface coating for everything from tubing to wound dressings.

Materials also could play a part in the defense against the stubborn bacteria. Last year, Gore (Newark, DE) unveiled its Dualmesh Plus biomaterial, which the company claims inhibited MRSA adherence during testing.

Using MRSA-inhibiting materials and coatings for indwelling devices warrants some attention. Biofilm formation on indwelling devices accounts for only a portion of MRSA infections; however, considering the possibility of these infections—and incorporating features into devices to prevent them—could curb instances of infection and save lives. By doing so, we may not be able to exterminate the Superbug, but we can at least make every effort to keep it under control.

Shana Leonard, Managing Editor

Copyright ©2007 Medical Product Manufacturing News

You May Also Like