Mastering the Clinical Investigation

Patients expect to have access to safe and effective medical devices. In the United States, the medical device development process typically includes developing the product, collecting clinical data or other evidence on the product’s safety and effectiveness, and completing a marketing application in the form of a premarket approval (PMA) or premarket notification (510(k)), which is submitted to FDA. There are some devices which are exempt from this process.

For PMAs and some 510(k)s, CDRH coordinates with the Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA) to conduct bioresearch monitoring (BIMO) inspections. These inspections ensure the quality and integrity of clinical data that are submitted to the center to support marketing applications. They also assess the protection efforts in place for the individuals participating in clinical trials for the associated investigational device.1

After reviewing the application and the results of the BIMO inspection, as applicable, the agency determines whether the application meets the necessary criteria for approval or clearance. If it does, the agency notifies the company that it can market the product. Although most firms appear to be doing an adequate job with their clinical studies, some sponsors need to improve the oversight of their clinical trial programs, as evidenced by the outcome of recent CDRH-BIMO inspection activity.

To explore industry’s current management of clinical trial practices, a working group of representatives from CDRH and industry created a survey. This survey, distributed to medical device quality and regulatory professionals, was intended to obtain data regarding both processes and systems already in place to mitigate potential noncompliance with regulatory requirements, as well as elements that could be implemented or improved to promote compliance. The primary objective of the survey was to demonstrate that a firm’s investment in quality, at the initial stages of product development and through the clinical trial process, outweigh the cost of fixing deficiencies uncovered during an FDA field inspection.

This article provides a brief overview of the clearance and approval process, as well as a discussion of deficiencies discovered during CDRH-BIMO inspections and examples of sanctions imposed against sponsors by the agency. It also discusses the results of a survey for which respondents provided information about their current clinical trial practices as it relates to regulatory compliance, and excerpts from interviews with three seasoned practitioners who have established and observed the elements of an effective clinical development program.

Part 1: The Product Clearance or Approval Process

|

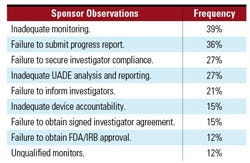

Table I. The most frequent 483 sponsor observations in FY 2008.4,5 |

To market a medical device in the United States, manufacturers must determine whether their product falls within the definition of a device, which is contained in section 201(h) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.2 Next, the firm makes an initial assessment by finding the matching description of the device in the classification panels, located in the Code of Federal Regulations, 21 CFR Parts 862–892. Classification of a device is based on intended use and indications for use of the device. There is a risk-based system based on the level of control necessary to ensure the safety and effectiveness of the device, as follows:

Class I devices present the lowest risk, are usually exempt from 510(k), and are subject to general controls.

Class II devices typically require a 510(k) and are subject to both general and special controls.

Class III devices present the highest risk to the patient or end-user, generally require a PMA, and are subject to general controls.

Classification of a device ultimately affects the level of regulatory oversight that FDA must exercise, the type of marketing application that the manufacturer will need to submit, and the scope of required efficacy and safety data the firm will need to collect.3 The data in a 510(k) application must demonstrate that the device is substantially equivalent to a legally marketed device. A legally marketed device is a device that was marketed prior to May 28, 1976 or has been found substantially equivalent since that time. The data submitted in a PMA application need to demonstrate that there is a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness in the product, which is usually accomplished through clinical trials conducted under an approved investigational device exemption (IDE). Generally, all PMA applications and some 510(k) applications are required to contain supporting clinical data.

FDA has issued regulations, widely known as good clinical practice (GCP) regulations, which outline expectations for clinical studies for sponsors, clinical investigators, institutional review boards (IRBs), and certain vendors. For medical devices, these regulations include IDEs (21 CFR 812), protection of human subjects (21 CFR 50), IRBs (21 CFR 56), and financial disclosure by clinical investigators (21 CFR 54).

As previously noted, part of the review process for medical devices includes CDRH exercising due diligence in inspecting GCP-regulated entities. These BIMO inspections are conducted to verify the integrity of the data submitted to the agency, as well as the ethical rights and safety of clinical trial participants. GCP compliance is also assessed. The ORA investigator documents inspection observations on FDA Form 483. Significant departures from the regulations or repeated noncompliance can result in the issuance of a warning letter. As discussed in more detail later, FDA has at its disposal more severe penalties such as the application integrity policy (AIP), and the issuance of notice of initiation of disqualification proceedings and opportunity to explain (NIDPOE) letters for more egregious violations. These measures can result in significant costs to the firm in terms of time, money, resources, marketing delays, poor publicity, and tarnished reputations in the case of a NIDPOE sanction.

Part 2: Examples of Deficiencies and Sanctions

|

Table II. The most frequent 483 sponsor observations in FY 2007.4,5 |

Over the past two years, CDRH’s Division of Bioresearch Monitoring has performed more than 300 inspections per year. Sponsor inspections generally represent approximately 15% of the total inspections conducted. In FY 2008, CDRH conducted 301 total inspections, 57 of which were sponsor inspections. During that time period, the division issued 28 warning letters, four of which were directed at device sponsors. The most frequent observations documented on FDA Form 483s are outlined in Table I.

FDA cited similar observations in the year before. In FY 2007, CDRH conducted 323 BIMO inspections, 40 of which were sponsor inspections. A total of 29 warning letters were issued during that time period, eight of which were addressed to sponsors. The most frequent sponsor observations documented on FDA 483s are outlined in Table II.

Monitoring concerns were one of the leading deficiencies for 2007 and 2008, and historically have been a frequent FDA observation. Notably, many of the other citations, such as securing investigator compliance and device accountability, can be attributed to inadequate monitoring. If these problems are caught early on by the study monitor and are escalated to upper management, as needed, the sponsor could correct the problem or drop the site as stipulated by the regulations (21 CFR 812.46(a)). In addition to achieving regulatory compliance, effective monitoring most likely results in a substantial cost saving for the company because it can ensure adherence to the protocol, which likely results in the collection of good quality data.

Another frequent observation pertains to unanticipated adverse device effect (UADE) reporting. Investigators who conduct clinical device trials under an investigational device exemption (IDE) are required to report UADEs to both the sponsor and IRB as soon as possible, but no later than 10 working days after the investigator first learns of the effect (21 CFR 812.150(b)(1)). Similarly, the sponsor is required to evaluate the UADE and report the results of this evaluation to FDA, all reviewing IRBs, and participating investigators within 10 working days after the sponsor first receives notice of the effect (21 CFR 812.46(b), and 21 CFR 812.150(b)(1)). Noncompliance with these regulations was observed quite frequently during the 2007 and 2008 inspections.

If FDA uncovers condition violations of the regulatory requirements during an inspection, FDA may take enforcement action, such as the issuance of a warning letter. Any company that has received a warning letter knows all too well that responses require a good deal of time and resources. FDA posts the warning letters and, in some cases, company responses on its Web site. The public can also obtain these documents by making a formal request under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). A review of CDRH-BIMO warning letters issued to sponsors during the same 2007–2008 time frame, showed similar trends in the types of 483 observations noted.

As previously noted, one enforcement measure that CDRH can use is the AIP. If the inspectional observations reveal a pattern or practice of wrongful acts that raise a significant question regarding the reliability of data in a company’s applications, the center may issue an AIP letter. This could stop the review of one, some, or all of the submissions from the applicant that are affected, either directly or indirectly, by the questions about reliability of data. Additionally, FDA can require a sponsor to submit further data, provide evidence of system audits, and submit a corrective action plan.6 The AIP was invoked in a example, outlined here.

Example 1. An IDE was submitted to treat infants with hydroplastic left heart syndrome. The sponsor reported several emergency uses of the device to FDA. However, these devices had been modified substantially, causing the FDA to request that a separate IDE be submitted. An IDE was submitted per FDA’s request and was conditionally approved. Due to subsequent concerns about data integrity, a “for cause” inspection was completed. Numerous deficiencies were noted during this inspection, resulting in a warning letter being issued. The following deviations were included in the warning letter:

Failure to maintain accurate records of adverse events.

Failure to notify FDA of emergency uses within five working days.

Failure to ensure proper monitoring of a clinical investigation and to secure investigator compliance.

Failure to select qualified monitors.

Failure to maintain complete records of shipment and disposition of devices.

As a follow-up, the sponsor was inspected again by FDA. During the second inspection, the sponsor was found in violation of the following:

No written SOPs for ensuring prompt compliance or corrective action for protocol deviations.

No disciplinary action was taken by the sponsor when noncompliance occurred.

Investigational sites did not document reasons for protocol deviations.

Device accountability was not reconciled as required by the sponsor’s SOPs.

The sponsor notified FDA through submission of a supplement to their second IDE that there were three unreported emergency uses of the device that resulted in three deaths prior to approval of the IDE application. In light of this information, the FDA conducted a third “for cause” inspection of the sponsor to determine whether the compassionate or emergency use provisions were being abused. The third inspection revealed the following:

An additional four emergency use cases were discovered during the inspection that were not reported to FDA within five working days.

Device accountability records failed to account for more than 20 devices.

Adverse events were not reported in a timely manner even though the firm had a corrective action plan in place.

Because of the continuing nature of noncompliances observed during multiple inspections, the FDA asked the sponsor to meet with FDA officials to explain their actions. The sponsor was placed on an AIP agreement with FDA and remained on AIP for approximately two years.

NIDPOE letters are another means by which FDA secures compliance. NIDPOE letters inform the recipient clinical investigator that FDA is initiating an administrative proceeding to determine whether the clinical investigator should be disqualified from receiving investigational products pursuant to FDA’s regulations. Generally, FDA issues a NIDPOE letter when it believes it has evidence that the clinical investigator repeatedly or deliberately violated FDA’s regulations governing the proper conduct of clinical studies involving investigational products or submitted false information to the sponsor.7 Another example resulted in both NIDPOE and AIP action.

Example 2. Two IDEs were submitted for knee and hip replacement devices. The sponsor informed FDA that it had implanted a significant number of devices prior to the approval of the IDE in the hip study. These subjects did not receive informed consent nor were they aware that they had received an investigational device. The sponsor stated that they sold these investigational devices by physician’s prescription. Based on this information, FDA decided to conduct “for cause” inspections of the sponsor as well as the clinical investigators. The inspections revealed the following:

Failure to ensure control of the investigational device.

Failure to document and report adverse events.

Failure to ensure the clinical investigators obtain informed consent from subjects prior to the use of the device.

Failure to utilize IRB-approved informed consent forms.

Failure to adhere to study protocol.

Failure to ensure that clinical investigators obtain IRB approval before initiating the study.

Failure to ensure maintenance of device accountability records.

Failure to obtain IDE approval and IRB approval prior to initiating study.

Failure to ensure proper monitoring of the clinical investigation.

Failure to obtain financial disclosure or investigator agreements for each investigator.

Based on the inspections, the FDA took the following action:

Issued a warning letter to the sponsor.

Issued a NIDPOE to the clinical investigators.

Requested that no additional patients be enrolled in the study and that the sponsor send a patient notification letter to those who had received the device without informed consent.

The sponsor also needed to prepare a corrective action plan and audit all of the data from the hip study. The sponsor was placed on AIP. In response to the agreement, the sponsor submitted a draft audit and corrective action operating plan, however, this plan was inadequate due to its lack of specificity in terms of actions to be taken and documentation for corrective actions already made.

The sponsor then notified FDA that one of its hip devices, which was approved in Europe but not in the United States, had been imported to the United States and implanted in 170 patients. These sales were made pursuant to the physicians’ “prescriptions” as custom devices. FDA responded by issuing inspections of the two clinical investigator sites where the foreign devices were implanted. Additional warning letters were issued to the sponsor and clinical investigators. The sponsor remained on AIP for approximately 3.5 years.

Part 3: Current Practices of Survey Respondents

A survey was conducted to determine the amount of resources medical device and drug firms devote to their clinical trials and best practices in carrying out their clinical trials programs in accordance with GCP. A working group with representatives from Compliance-Alliance, The Lindyn Group, and FDA conducted the survey.

Demographics. Fifty-three respondents from large, medium, and small medical device, drug, and combination products firms who are in the clinical development stage or manufacturing stage completed the survey. These firms ranged from companies that had one to more than 10 locations. Respondents’ companies currently manufacture between zero and 40 products. The firms completing the survey reflected the range of companies supplying medical devices to patients worldwide. Seventy-six percent of the firms had conducted one or more clinical trials that had been included in an application submitted to FDA for which they received marketing approval or clearance.

Locations of Manufacturing Facilities. Most firms (74%) had the majority of their employees based in the United States, while 26% had their employees scattered among various countries. Firms were divided on the number of facilities worldwide, with 40% having between one and three facilities and 39% having more than 10 facilities.

Clinical Trials. When asked about the number of clinical trials they were conducting globally, most firms indicated that they were conducting between one and five; however, the number of clinical trials ranged from zero to greater than 50. Although these trials were conducted both in the United States and other countries, more trials in this sample were conducted inside the United States. The number of clinical investigator sites in firms’ clinical trials ranged from one to more than 100, with two to five sites being the most common size of the smallest clinical study and 11–25 sites being the most common size of the largest clinical study.

|

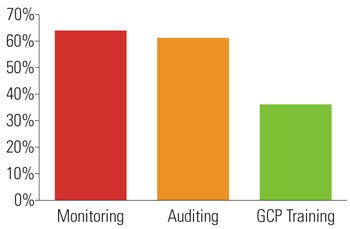

Figure 1. Percentage of respondents that outsource key GCP functions. |

Responsibilities of RA-QA Officials. Because GCP compliance generally falls within the responsibility of the regulatory or quality assurance professionals, the role of these employees was explored. The number of full-time equivalent employees that firms used to perform the regulatory and quality function generally ranged from zero (this was probably a virtual company) to greater than 50 (see the sidebar “RA/QA/QC Responsibilities.”).

Functions That Were Outsourced. Most firms used their internal staff to perform the majority of the functions listed earlier, with the exception of three key functions: monitoring, auditing, and GCP training. See Figure 1 for details regarding the percentage of respondents that outsource monitoring, auditing, and GCP training.

The most common reasons firms mentioned for outsourcing these functions included the specified or unique experience of the vendor, as well as logistical reasons, such as distance or language issues. The qualification process for these vendors was assessed. To select vendors, firms used the criteria provided in Figure 2.

|

Figure 2. Percentage of respondents that take steps to qualify vendors. |

As previously discussed, inadequate monitoring has continually been one of the most frequent CDRH-BIMO inspection observations. Because the responsibility for ensuring oversight of the clinical trial remains with the sponsor, it is critical that firms evaluate potential vendors carefully. Although it is promising that such a high percentage of respondents confirm that a part of vendor selection is through a qualification process, there may be a gap in that qualification process. With regard to auditing, the industry standard is to conduct an initial qualification vendor audit and then follow-up audits for that vendor periodically, usually once every two years. Perhaps vendors conducting such an important function, such as monitoring, need to be audited more frequently. Additionally, it is important that vendors are assessed systemically and that the vendor has a closed-loop system. If a sponsor conducts a clinical investigator site audit, for example, and observes inadequate monitoring performed by a vendor, it is critical that such information is fed back to the vendor’s management and the sponsor’s management. This can be achieved via an effective corrective and preventive action (CAPA) system, which is an integral part of a firm’s quality management system (QMS)—a requirement for device manufacturers. Monitoring and auditing are discussed in more detail below.

|

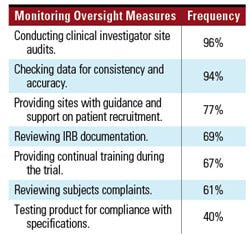

Table III. Common sponsor activities taken to ensure adequate monitoring. |

Monitoring Activities. Respondents devoted various proportions of their clinical trial budget to monitoring activities associated with clinical trials. While many firms were spending less than 25% of their clinical trial budget on monitoring, others were spending between 25–55% of their budgets for this activity. Some respondents reported spending greater than 75% of their budget on monitoring, but this was the exception rather than the rule. To ensure adequate monitoring, the respondents engaged in the activities outlined in Table III.

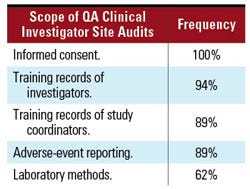

Auditing Activities—Clinical Investigator Sites. Similarly, the audit process was explored. An effective audit program is an important component of ensuring GCP compliance. During clinical investigator site audits, respondents stated they evaluated the key processes outlined in Table IV.

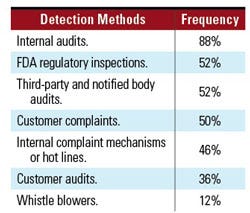

Discovering and Preventing Noncompliance. The survey asked about measures firms were using to detect instances of actual or potential areas of noncompliance with GCP requirements or adherence to the firms’ policies and procedures. Respondents reported using the methods outlined in Table V (p. XX).

|

Table IV. Processes assessed during QA clinical investigator site audits. |

Firms may consider using internal audits in combination with other mechanisms to discover and prevent deficiencies. Reliance on regulatory inspections as an isolated way to promote compliance and discover and prevent noncompliance is not necessarily an effective mechanism. These inspections are typically conducted at the end of clinical trials, when all data has already been submitted. The costs incurred by the company at this point in the marketing application process, including delays, far outweigh the costs incurred to detect and prevent noncompliance from the beginning.

When asked to rank areas of noncompliance that respondents observed most frequently during their careers, the following deviations from the regulatory requirements, in order of frequency, were noted:

Lack of protocol adherence.

Inadequate record keeping.

Training deficiencies.

Inadequate safely reporting.

|

Table V. Methods used to detect noncompliance. |

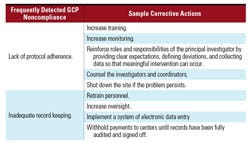

Respondents were also asked to provide corrective action for areas in which noncompliance was frequently noted. Sample corrective actions for the two most frequently observed areas by industry are provided in Table VI. Implementation of more effective training was uniformly offered as a corrective action, regardless of the deficiency.

Similarly, when asked about the most effective preventive actions to ensure GCP compliance, most respondents mentioned training, followed by monitoring and auditing, followed by appropriate follow-up action for noncompliance. Notably, as outlined earlier in Part 2, industry’s GCP noncompliance observations differ from CDRH-BIMO inspection observations. This is a gap that needs to be explored by both the industry and FDA.

Formal Training Program. Respondents appeared to be aware that if they want their staff to comply with regulatory requirements and the firm’s internal policies and procedures, they needed to have a rigorous training program. In fact, 75% of respondents reported that they had a formal training program for their in-house

|

Table VI. Corrective actions for frequent industry-detected GCP noncompliance. |

staff. However, only 21% reported having such a program for their clinical investigators, and only 4% reported having such a program for their vendors. The paucity of formal training for clinical investigators and vendors, in addition to the need for training identified by industry above, suggests that there is room for improvement in this area. To promote compliance, all firms should evaluate the training programs in place for clinical investigators and vendors as well as staff. Additionally, adequate documentation of training should be maintained in the firm’s files.

Part 4: Implementing An Effective Clinical Development Program

Ideally, firms are using effective CAPA measures to ensure GCP compliance, rather than reacting to regulatory inspection observations. The survey identified common practices within the industry. To identify elements of effective clinical development programs, three experienced practitioners shared their observations related to how they have ensured compliance with device regulations and achieved success in the clinical trial arena.

The practitioners are Virginia Perry, president of Perry D’Amico and Associates, Michael Hamrell, president of Moriah Consultants, and Louise Peltier, regulatory affairs consultant (see the sidebar, “Practioners Interviewed.”) . Excerpts of their responses to GCP compliance questions are presented here.

As previously mentioned, there appears to be a gap between CDRH-BIMO inspection observations and those identified by industry. While monitoring and UADE reporting have consistently been two of the most frequent FDA Form 483 observations, industry reported a high frequency of deviations from the requirements pertaining to protocol adherence and inadequate record keeping findings. The responses provided by the practitioners provide some interesting insights. Hamrell, for example, reported that two of the six most important elements of a robust regulatory program include effective monitoring, specifically:

“Monitoring vigilantly on a regular basis.”

“Using qualified, knowledgeable, well trained monitors.”

Similarly, Perry suggested, “creating and implementing a comprehensive audit/monitoring program to assure compliance with regulatory requirements.”

Monitoring Resources

When pressed for more information on how to implement and manage a successful monitoring program, two out of three practitioners stressed the importance of devoting adequate resources to the monitoring function. Notably, a wide variety of budget allocation to monitoring was shown across industry survey respondents—a quarter of respondents indicated that less than 25% of their clinical budget is allocated to monitoring. All of the practitioners fell in line with industry in regards to the importance of training and qualification of monitors.

“When developing a monitoring plan, be realistic and expect to need more time and resources than you think. The plan should be flexible enough so that if you encounter issues, you can amend the plan and do more monitoring.” (Hamrell)

“Be sure to establish and maintain an adequate schedule for monitoring.” (Perry)

Training and Qualification for Monitors

“A qualified monitor needs to be experienced in clinical trials, GCP, device development, and the practice of medicine for the disease of interest.” (Hamrell)

“The qualifications of the monitors need to be mandatory and the qualifications and knowledge need to be specific to the products being monitored. Specific training needs to be conducted and certified.” (Perry)

“Clinical, as part of its GCP program, needs to adequately qualify monitors.” (Peliter)

UADE Tracking and Documentation

Along with monitoring, UADE reporting is another frequent CDRH-BIMO inspection observation. The practitioners shared their thoughts on ways to secure compliance in this area. Two common elements were the use of a good tracking system, including adequate documentation (e.g., forms) and appropriate sign-off to capture required information, and training.

“Use a tracking system to know when each report is received and when it is due to be mailed to FDA, sites, etc.” (Hamrell)

“Develop adequate forms for adverse-event reporting and monitor the use of the forms.” (Perry)

“Require that there be at least one individual from regulatory affairs or compliance who must approve both the initial report (and has the authority to report even if it is in conflict with the medical director’s decision) and the final report. . . Have a compliant, formally approved procedure in place prior to approving any clinical study protocols.” (Peltier)

UADE Training

“Have a safety product group with qualified medical and product experts who review and assess each UADE received.” (Hamrell)

“Train personnel on how to handle adverse events.” (Perry)

“Include UADE reporting procedures in the training program for all clinical research, quality, development, regulatory affairs, CRO, and any internal support personnel.” (Peltier)

Failure to inform investigators, FDA, or the IRB is another frequently observed noncompliance in CDRH-BIMO inspections. Notably, only one survey respondent mentioned failure to inform FDA or IRB as the single most frequent noncompliance observed. The practitioners provided advice on ways to help the investigator comply with the regulatory requirements contained in 21 CFR 812.45. In addition to ensuring an investigational plan and reports of prior investigations are in place, companies should observe the following advice:

“Develop a newsletter or similar document to regularly update the team about the trial program. When formal amendments are sent out, use priority mail, return receipt directed to the principal investigator to assure he/she receives the information. Require investigators to read and acknowledge receipt of the information.” (Hamrell)

“Formally communicate any changes to the clinical study to the investigator. . . . Such changes need to be adequately documented, approved, and signed by the responsible individuals managing the clinical study. Revision history is strongly recommended in order to maintain a history of such changes.” (Perry)

“Establish a procedure for the development, review, and approval of clinical study protocols. Any revisions to the trial program. . .must be reviewed and approved prior to implementation. . . . The procedure should also cover a copy of the draft letter, which will accompany the revised documents that will be sent to the clinical sites and be included with the final document package for approval.” (Peltier)

Protocol Adherence

Whereas few industry respondents acknowledged the common regulatory inspection observation of adequately informing necessary parties of an issue that needed to be addressed, the majority of industry did note protocol adherence as a frequently found noncompliance. To address this common industry observation, the practitioners provided the following input with regards to protocol adherence:

“Tie payment for completed subjects to quality of data. If the investigators make a mistake, they should pay for it.” (Hamrell)

“Obtain clear, signed agreements with the investigators regarding clinical protocols and conduct monitoring visits to assure protocol compliance.” (Perry)

“Identify known violators and increase the frequency of clinical monitoring of those sites accordingly. Implement a program to withhold payment if the problem persists based upon monitoring observations.” (Peltier)

Conclusion

Patients have a right to expect that their medical devices will be safe and effective for their intended use. The expectation is fulfilled only when the firms that develop and manufacture devices do so in accordance with accepted practices, codified as GCP regulations in the Code of Federal Regulations. When companies follow practices not in compliance with GCP, the consequences can be dire for both the firm and, more importantly, the unsuspecting clinical trial participants.

The alignment between deficiencies found by CDRH’s bioresearch monitoring activities and those in industry is interesting. ORA field inspectors consistently document observations related to monitoring, informing investigators, FDA, and IRBs, and UADE reporting, for example, whereas industry indicates that observations such as lack of protocol adherence and inadequate record keeping are more common. Although industry has suggested many of the actions needed to decrease the incidence of these important deficiencies, the survey data suggest that the budgets that may be required to implement these actions may not be available. The practices identified in this paper related to auditing, monitoring, and training are cost-effective measures for improving the quality of medical companies’ new product submissions. These can help to ensure the reliability and integrity of data collected during the clinical trial process, and ultimately safeguards the health of citizens both in the United States and around the world.

References

Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff—The Review and Inspection of Premarket Approval Applications under the Bioresearch Monitoring Program (Rockville, MD: FDA, 2008); available from Internet: www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm071557.htm.

21 USC 201(h)

“Device Advice” (Rockville, MD: CDRH, updated August 4, 2004); available from Internet: www.fda.gov/MedicalDevice/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/Overview/ClassifyYourDevice/default.htm.

Data retrieved from CDRH’s Internal Inspectional Database

FDC Reports, The Silver Sheet 13, no. 1 (January, 2009).

“Application Integrity Policy Procedures” (Rockville, MD: FDA, March 5, 1998); available from Internet:

www.fda.gov/downloads/ICECI/EnforcementActions/ApplicationIntegrityPolicy/UCM072631.pdf.“FDA Regulatory Procedures Manual,” Chapter 5—Administrative Actions (Rockville, MD: FDA, March 2009); available from Internet: www.fda.gov/downloads/ICECI/ComplianceManuals/RegulatoryProceduresManual/UCM074324.pdf

Bibliography

Draft Guidance for Clinical Investigators, Sponsors, and IRBs; Adverse Event Reporting—Improving Human Subject Protection [online] (Rockville, MD: FDA, 2007); available from Internet: http://www.fda.gov/OHRMS/DOCKETS/98fr/07d-0106-gdl0001.pdf.

Guidance for Industry: ICH E6, Good Clinical Practice: Consolidated Guidance [online] (Rockville, MD: FDA, 1996); available from Internet: www.fda.gov/downloads/regulatoryinformation/guidances/UCM129515.pdf.

Michael E. Marcarelli et al., “Building Quality into Device Clinical Trials, Part 1,” Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry 28, no. 7 (2006): 60–70.

Michael E. Marcarelli et al., “Building Quality into Device Clinical Trials, Part 2,” Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry 28, no. 10 (2006): 56–67.

“Running Clinical Trials” [online] (Rockville, MD: FDA); available from Internet:

www.fda.gov/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/RunningClinicalTrials/default.htm.

“Regulatory Procedures Manual March 2009” [online] (Rockville, MD: FDA, 2009); available from Internet:

www.fda.gov/ora/compliance_ref/rpm/default.htm.

Marci Macpherson, is senior QA auditor at Abraxis BioScience. Bridget Foltz is policy analyst, Office of Good Clinical Practice, and Jonathan Helfgott is FDA consumer safety officer for CDRH. Nancy Singer is president of Compliance-Alliance LLC. Sue Hocker is principal for The Lindyn Group.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like