Why the Future of Disease Diagnosis Needs Engineers

December 9, 2015

Engineers are needed to build new diagnostic devices to truly get at the cause of disease, says pioneering cellular biologist Jamey Marth.

Chris Newmarker

|

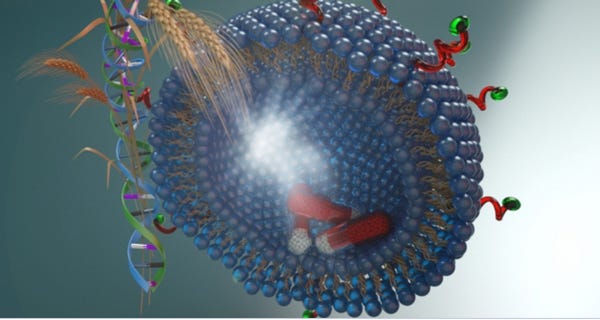

What about the role played by molecules other then nucleic acids, and the proteins they help create? What about glycans and lipids? (Image courtesy of the Center for Nanomedicine, UC Santa Barbara) |

Genomics is about as popular in science circles as Adele is in pop music. Sequencing is getting cheaper and faster and the molecular editing system known as CRISPR offers opportunities to edit DNA in living cells.

That's all yesterday's news, though, for Jamey Marth, PhD, whose previous achievements include the conception and co-development of the Cre-Lox conditional mutagenesis used for genetic editing.

|

Jamey Marth |

What about the role played by molecules other then nucleic acids, and the proteins they help create? What about glycans and lipids?

"I'd like to suggest we're entering the post-genomic era," says Marth, who is director of the Center for Nanomedicine at the University of California, Santa Barbara. (See Marth deliver a talk about nanotechnology and engineering at MD&M West.)

Cancer, diabetes, infectious diseases, neurodegenerative diseases--none of these diseases can be described simply though DNA, Marth says. Think, for example, how monozygotic ("identical") twins share the same DNA, but not the same diseases.

"So what's happening? We're getting environmental influences: things we eat, bugs that we're infected with, chemicals we're in contact with. These are describing disease, and this is what we need to understand. And you can't do that without looking at metabolism in the cell."

Engineers have an important role to play in figuring this out, because the devices needed to effectively analyze these interactions are not like anything that is presently out there, Marth says. Marth is presently working with bioengineering colleagues on such devices, which Marth thinks will greatly increase diagnostic abilities.

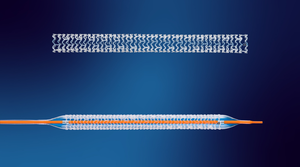

The devices need to be small and high throughput, with the ability to interrogate hundreds of molecules, sometimes in parallel. And they need to be able to rapidly process 5 to 10 ml of blood, according to Marth. "That's necessary, because some of the metabolites that we need to be measuring are at low enough concentration that we need to measure, for example, 5 ml of blood."

That's a different type of IVD device than what is presently out there, according to Marth.

"Most of engineers are focused on high sensitivity, but they're also focused on small sample volume, and that's not going to be sufficient to make a breakthrough in clinical needs," Marth says.

Marth's IVD strategy has shown promise. For example, Marth and his colleagues recently published findings about how multiple factors, including circulating enzymes called glycosidases, create the mechanism through which secreted proteins age and turnover at the end of their life spans. The research, according to Marth, provides a window into the origin of such diseases as sepsis, diabetes, and inflammatory bowel disorders.

Research led by UC Santa Barbara biologist Michael Mahan, of which Marth was a co-author, explained how Salmonella uses the intracellular environment inside the white blood cells they occupy to resist antibiotics that would kill them if they were in a petri dish. The research suggests that there may be drugs out there that may not kill Salmonella in normal petri dish lab tests, but would do so inside the body.

On the therapeutics side, Marth and his colleagues have been working on nanoparticles that target cancer cells using the signature sugars on cancer cell walls.

"We're one of only the handful of research laboratories that are looking at this perspective," Marth said. "We may be ahead of our time. ... But as a result, the advancements being made in understanding the cellular origins of disease are astounding. And the only way we can move this forward is to get bioengineers onboard, people who are interested to committing to generating the next generation of diagnostics and therapeutics."

(See Marth deliver a talk about nanotechnology and engineering at MD&M West.)

Chris Newmarker is senior editor of Qmed and MPMN. Follow him on Twitter at @newmarker.

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to our daily e-newsletter.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like