How to Make Flexible Electronics Stick

October 7, 2015

Skin interface and adhesives present a major design opportunity for flexible electronics pioneer MC10 and others.

Chris Newmarker

|

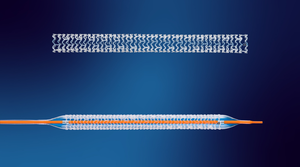

MC10 has technology for flexible, stretchable electronics. (Photo courtesy of MC10) |

When it comes to designing flexible electronics to stick on the skin, MC10 has accomplished a great deal when it comes to thinning circuits down to micrometer levels and designing interconnects in the structures of the electronics to make them flexible and stretchy.

It is making the sensors stick--finding the right device-skin interface--that presents a design challenge (or opportunity?) these days, requiring expertise in materials science and adhesives, says Roozbeh Ghaffari, co-founder and vice president of medical technology at MC10 (Lexington, MA).

"A lot of that time is spent at that level, probably more so than building the circuits," Ghaffari said Wednesday at MD&M Philadelphia. (See Ghaffari discuss the next generation of sensors and flexible electronics for medical devices at Minnesota Medtech Week, November 4-5 in Minneapolis.)

MC10 is not alone with design challenges around adhesives, either. Intelomed (Wexford, PA), which is developing a sensor that sticks on the forehead, has also found that making a device stick is a design challenge, Jill Schiaperelli, the company's CEO, said on the show floor at the Philly conference.

In studying the health sensors out their, MC10 found that many would leave a rach after 10 to 15 days on the skin. MC10 sought out dermatologists to figure out strategies around the problem.

"Typically, different types of silicone-based adhesives work," Ghaffari said.

Sweat pooling and the presence of hair needs to be considered.

"Really thin form factors and tuning adhesive properties is important to account for sweat, for hair," Ghaffari said.

There needs to be a balance between an adhesive that sticks, but doesn't take hair (or worse) along with it when it's removed.

"It has to be strong enough to stay and not delaminate, but it can't cause pain when it's removed. There's a tradeoff there," Ghaffari said.

For now, MC10 is working on devices on the skin that measure everything from movement to heart rate to temperature to ECG to EMG. The company is able to package together super thin sensors, a microprocessor flash memory, and Bluetooth LE. Along the way, it has solved a host of mobile health challenges.

"We focus on multi-location, better accuracy, clinical quality data, and are building an end to end system. ... Our next products are all pure health monitoring devices," Ghaffari said after his talk.

MC10, though, is researching the potential of someday pairing its electronics with existing drug-delivery patches that are on the market--a strategy that could allow MC10 to take advantage of adhesives strategies other companies have developed.

MC10, for example, already has a partnership with biopharmaceutical company UCB to develop symptom-tracking devices for patients with movement-tracking disorders. UCB happens to have a transdermal patch to deliver prescription drugs to Parkinson's patients.

(See Ghaffari discuss the next generation of sensors and flexible electronics for medical devices at Minnesota Medtech Week, November 4-5 in Minneapolis.)

Chris Newmarker is senior editor of Qmed and MPMN. Follow him on Twitter at @newmarker.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like