2000 Business Outlook: Creating the Future

Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry MagazineMDDI Article IndexCover StoryAt a time of tremendous technological innovation, device executives responding to MD&DI's exclusive annual survey express unprecedented optimism regarding current and near-term business conditions.

March 1, 2000

Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry Magazine

MDDI Article Index

Cover Story

At a time of tremendous technological innovation, device executives responding to MD&DI's exclusive annual survey express unprecedented optimism regarding current and near-term business conditions.

Be sure to read our companion piece, Survey Respondents Showcase Diverse Industry |

Amid seemingly unshakeable domestic prosperity and relative economic stability worldwide, top U.S. medical device company executives are expressing unprecedented optimism, both in assessing current business conditions and in predicting what will transpire over the course of the next year. And while the U.S. market—representing more than 40% of global consumption—remains the most popular as well as the most promising, larger firms in particular are newly enamored of opportunities in Europe and Asia.

These are among the major findings of MD&DI's exclusive eighth annual business outlook survey of device company executives. Administered for MD&DI by the independent research firm Readex Inc. (Stillwater, MN), the mail survey was conducted from October 18 to December 13, 1999 and tabulates the responses of 191 executives whose companies manufacture finished medical devices or in vitro diagnostics. (See sidebar for the survey methodology and a profile of this year's respondents.)

A BALMY CLIMATE

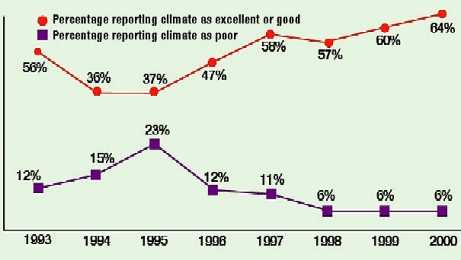

Figure 1. Respondents' rating of current business climate for the medical device and diagnostic industry as a whole.

In last year's survey, 60% of executives described overall business conditions for the industry as excellent or good. This year, the number increases to 64%—the highest rating since the survey began in 1993 and a substantial 27% above the rating accorded five years ago (Figures 1 and 2). Smaller companies appear even happier, with a good or excellent rating given by 73% of firms with sales between $1 million and $4 million. As was the case last year, only 6% of respondents characterize the current situation as poor, equaling the survey's record low.

Figure 2. Executive ratings of device industry business climate, 1993–2000.

"As the baby-boom generation ages, the device industry obviously has demographics on its side," says Steve Northrup, executive director of the Medical Device Manufacturers Association (MDMA; Washington, DC). "Investors, venture capitalists, and Wall Street in general are finally coming around to recognize this fact, and are concluding that there is a great deal of unlocked value in this industry. There now seems to be more interest and excitement regarding medical devices than there has been in a number of years."

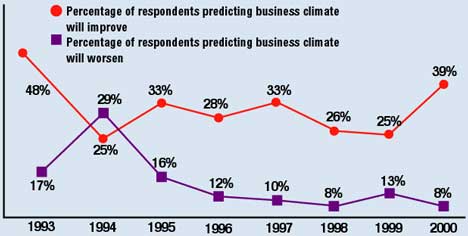

This upbeat mood is reflected in the expectations of executives anticipating business conditions in the year to come. Looking ahead, an impressive 39% of respondents—14% higher than last year—predicted that the business climate would improve over the next 12 months, reversing a two-year decline in this number (Figure 3). Particularly well-disposed to the future are small companies, with 45% of firms with sales under $1 million and 41% of those with no sales at all expecting an improvement in conditions for 2000. By contrast, whereas 63% of large companies (>$50 million) find current conditions excellent or good, only 14% expect further improvement next year.

Figure 3. Expectations of respondents for business conditions in the medical device and diagnostic industry, 1993–2000.

As a reflection of the general state of the domestic economy, the positive stance of executives directing smaller, younger, more-nimble companies is hardly surprising. By any standard, 1999 was one of the most remarkable—some might say bizarre—years in the economic history of the country. Led by Internet issues, the technology-driven Nasdaq index rose nearly 86%, with more than half of that astonishing jump occurring in the last two months of the year. "Concept" stocks—requiring only a CEO, a Web-related idea, and a business plan—soared into the stratosphere: one study claimed to show that stocks of companies with no earnings were up an average of 52% for the year, while those of companies reporting earnings were down 2%. The second half of 1999 also witnessed a surge of investor enthusiasm for biotechnology stocks—notably bioinformatics and genomics companies—as other sectors such as e-retailing began to cool off. "I think the device industry may be able to ride biotech's coattails somewhat," says Northrup, "but there are also many products under development that really blur the line between devices and biotech."

PATTERNS OF GROWTH

This year's survey confirms that actual sales figures are in line with respondents' more-subjective satisfaction with the general business environment. Overall, 58% of executives indicated that their companies experienced an increase in sales in 1999 compared with 1998, close to the 65% who had predicted such gains last year. As was the case a year ago, large companies led the way, with 92% (up 10% from 1998) reporting growth. Geographic disparity was also more pronounced this year, as 73% of device firms located in the West boosted their sales, compared with 60% in the Midwest, 57% in the Northeast, and a mere 39% in the South. The number for Western firms was a significant turnaround, since only 46% reported growth in 1998.

When executives were asked how they expected their sales volume to change in 2000, 71% predicted an increase in the coming year, with 20% of respondents anticipating growth of 40% or more. Those concluding that sales would remain approximately the same totaled 14%, while 1% expected a decline. The actual median increase in sales volume over the last five years is compared with executives' expectations in Table I.

Year | Actual Change in | Manufacturers' |

|---|---|---|

1995 | 10 | -- |

1996 | 12 | 20 |

1997 | 10 | 20 |

1998 | 8 | 15 |

1999 | 10 | 13 |

2000 | -- | 15 |

Table I. Actual sales gains for 1999 approached executives' expectations. |

One much-discussed model of the current state of the industry holds that small firms create and develop the innovative or breakthrough technologies, which are then acquired and refined by large companies. This premise finds support in the responses of executives to the survey question about research and development expenditures. For example, companies earning less than $1 million spend a sum equal to 15% of total annual sales on R&D, more than twice the 7% reported for companies earning over $50 million. Furthermore, the percentage of firms committing 30% or more of annual sales to R&D was more than seven times higher (15% to 2%) for small companies than for large ones. For all the device firms surveyed, the median expenditure level for 1999 was 8%, which was actually down from 10% in 1998.

MAKING THE CONNECTION

In addition to gathering information about patterns of growth in the sales of a company's products, MD&DI's survey seeks to ascertain how and where those products are being sold. Table II shows that survey respondents cite hospitals as the leading direct purchasers of their products, followed by distributors—the reverse of last year, when distributors led hospitals 65% to 63%. The prevalence of a direct selling channel to hospitals correlates with company size, declining steadily from 80% for the largest companies to 60% for the smallest.

Purchasers | Total (%) | 1999 Sales Volume in $Millions (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

< $1 | $1–$4 | $5–$49 |

|

Hospitals | 69 | 60 | 68 |

Distributors | 60 | 48 | 76 |

Physicians | 39 | 44 | 31 |

Group purchasing organizations | 23 | 8 | 22 |

Clinical labs | 20 | 8 | 23 |

Other healthcare professionals | 20 | 21 | 22 |

Freestanding outpatient centers | 17 | 10 | 16 |

Nursing homes | 13 | 10 | 16 |

Home-healthcare agencies | 12 | 13 | 10 |

Integrated delivery networks | 8 | 5 | 4 |

OEMs | 5 | 0 | 10 |

Other | 14 | 19 | 16 |

Table II. Direct purchasers of medical products manufactured by respondents (multiple answers permitted). |

Last year, a prominent refrain among small-company executives was that restrictive group purchasing organizations (GPOs) were damaging the prospects of smaller firms—a claim that appeared to be supported by the finding that GPOs acted as direct purchasers for 49% of large (>$50 million) companies but only 18% of small (<$1 million) companies. The contrast this year is even more acute—63% for large companies compared with 8% for small companies—and respondents are again lamenting the "false economics, politics, and fee structures of GPOs."

Jack Nally, vice president of Corporate Contracts Inc. (Erie, PA), which provides national accounts consulting, confirms that "because of consolidations within the industry, it is becoming increasingly difficult for small manufacturers to bring their products to the marketplace and eventually onto a GPO contract portfolio. The book of business that the large, multicompany corporations have simply outweighs the small manufacturers to such a degree that the GPOs are ignoring them."

Smaller companies, Nally suggests, need to find creative ways to work with a GPO's existing portfolio: "If a GPO has a contract with a competitive brand in the acute-care market, for example, a company can ask to be considered for an alternate site, or can propose certain model numbers of its product line that don't compete against existing products. I'm not suggesting that it's easy, but there are still opportunities—it just requires much more effort and expertise than it did as recently as five years ago."

There is, however, a new wave in the distribution channel, though its magnitude remains to be determined: the advent of Internet e-commerce service providers, like Neoforma or Medibuy, whose goals include transforming and extending the existing sales and distribution modalities. "The dot-coms coming on the scene open up a whole new realm of possibilities," says Nally. "They say they want to be vendor-neutral, and they're willing to work with practically any manufacturer. Because they're not warehousing and don't have any brick-and-mortar presence, it doesn't cost them anything to have all these different brands, whereas a traditional distributor has to consolidate the number of lines it carries in order to keep costs down. If I were a small manufacturer, I would strongly consider at least investigating the dot-coms and trying to pursue distribution that way."

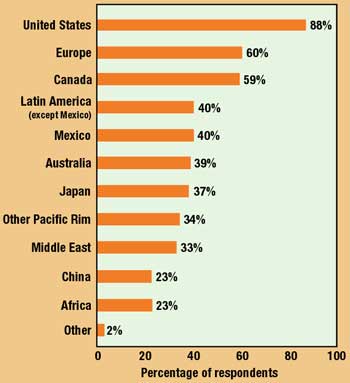

Figure 4. Current markets for medical device manufacturers, as indicated by survey respondents (multiple answers permitted).

Figure 4. Current markets for medical device manufacturers, as indicated by survey respondents (multiple answers permitted).

Nally stresses that the era of Internet distribution is still in its infancy, and that both its "ultimate impact and effectiveness are still in question. I think in the near future we're going to see more specialization among the Web firms. I also think we'll see a dot-com either purchase a GPO or a GPO go after a dot-com—in other words, the two markets will begin to merge. It's certainly exciting—the whole scene is evolving so fast."

BRAVE NEW WORLD

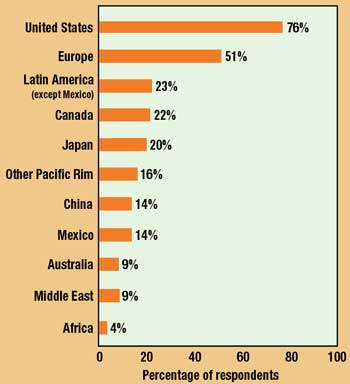

How a company distributes its products is in part a function of geographic markets. In the main, the executives' assessment of key markets for 1999 closely resembles the previous year's results, as does their estimation of markets representing the best opportunites for increased sales in 2000 (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 5. Markets representing the best opportunities for sales growth in 2000, as indicated by survey respondents (multiple answers permitted).

Figure 5. Markets representing the best opportunities for sales growth in 2000, as indicated by survey respondents (multiple answers permitted).

While it is to be expected that, given their superior resources, big companies are involved in more markets, what is surprising this year is the degree to which the largest companies identify Europe as offering the greatest potential for growth. One year ago, 70% of large-company executives tabbed Europe as the most promising market, as opposed to 68% for the United States. In the current survey, 88% of respondents at the biggest companies selected Europe versus only 59% for the U.S.—the 2% gap widening to nearly 30%. Reacting perhaps to an increasingly crowded domestic marketplace, it seems clear that big companies—who should be in a position to know—are confident that the European Union, its common currency, and the demise of national restrictions and regulations will have the effect of opening the continent to global competition.

If large device companies have concluded that an international market affords the most promise, it should follow that they are gearing up their operations outside the United States to take advantage of the opportunity. Responses from large-company executives indicate that this is in fact the case: for example, 92% of large companies now manufacture outside the United States, up 32% from last year. At least a majority of the biggest firms conduct distribution/sales (76%), product design (70%), assembly (67%), product R&D (65%), clinical trials (61%), packaging/ labeling (61%), and, for the first time, initial regulatory approval (51%) abroad. In each of these categories, percentages have increased substantially since the last survey, several by approximately 20%. By contrast, not one of these activities is currently conducted abroad by more than 21% of small firms.

But the international market, and Europe in particular, is not the exclusive province of far-flung, multinational conglomerates. Mark Gart, president of MBG Technologies Inc. (Newport Beach, CA), a small company that manufactures noncoherent light sources for photodynamic therapy (PDT), describes how his firm developed and tested its devices in the United Kingdom, where "since the mid-1980s, PDT had been going on at the research and university level to a somewhat more significant degree than in the United States."

Currently leasing its lamps to several research centers, the company's familiarity with the market and with potential European users of the devices should aid with eventual sales efforts in Europe, which will begin once the firm has initiated its regulatory application process in the United States. "European authorities have always been quite open to cooperating with their medical communities in helping develop new protocols and methodologies," says Gart. "From what I've been told by a number of venture capitalists, it's become almost standard operating procedure to start working with a device in Europe before bringing it back to the States."

THE PERILS OF PROGRESS

The evocation of a small company planning its regulatory approval strategy brings us to the all-important topic of FDA. The fiscal 1999 annual report from the agency's Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) was prefaced by a letter in which new center director David Feigal, MD, summarized several of CDRH's significant activities over the past year.

"For example," wrote Feigal, "review times for 510(k) submissions during FY99 were the lowest in nearly a decade. At the same time, we maintained last year's faster review times for premarket approval (PMA) applications, and acted on PMA supplements at a near-record pace—despite receiving more of these submissions than in any fiscal year since the early 1990s." The full report noted that average FDA review time and average total time to clearance for 510(k)s were 80 and 102 days, respectively. Total elapsed time to approval was 12.5 months for PMAs and 3.9 months for PMA supplements.

Regarding the implementation of the FDA Modernization Act of 1997 (FDAMA), Feigal contended that CDRH has lived up to its motto of "on track, on time." When queried as to the effects of FDAMA, 16% of respondents to MD&DI's survey said that their business had improved as a result of the legislation, up from 13% last year. Interestingly, both companies with no sales (28%) and those with revenues over $50 million (27%) reported higher-than-average benefits related to FDAMA.

Notwithstanding these modest improvements, MDMA's Northrup is doubtful that "very many companies can look specifically at FDAMA and say, 'Because of this particular provision, my business is so much better.' I think that 'FDAMA implementation' is probably taken by a lot of people to mean the general modernization of FDA—not just what was in the law but some of the work in reengineering the agency that Bruce Burlington did and that David Feigal is continuing. However, not every position stated by Dr. Feigal or other top people at FDA necessarily gets translated down to the actual front-line work of the reviewers and inspectors."

Jonathan Kahan, a partner in the Washington, DC, law firm of Hogan & Hartson, acknowledges that "under Bruce Burlington and Susan Alpert there were significant advances, such as FDA reducing the number of low-risk 510(k)s being reviewed through exemptions, or trying to expedite the review of high-risk products that have great value. However, I think the biggest problem we face is reduced FDA resources, which is affecting the agency's ability to replace reviewers and scientific personnel. FDA has essentially hit the wall in terms of how much they can use FDAMA to further streamline their processes, and I believe we're already seeing a slowdown in review times." Survey results seem to confirm that some reviews are taking longer: for example, the number of large companies encountering 510(k) clearance delays rose to a startling 61% this year, from only 17% in 1999 (Table III). PMA delays for large companies increased as well, from 11 to 25%.

FDA-Related Problem | Total (%) | 1999 Sales Volume in $Millions | |

|---|---|---|---|

< $1 | $1–$4 | $5–$49 |

|

510(k) clearance delays | 25 | 15 | 16 |

GMP/QSR inspection problems | 9 | 5 | 7 |

PMA/PMA supplement clearance delays | 6 | 0 | 0 |

MDR/user reporting problems | 4 | 3 | 4 |

Enforcement actions (injunctions, seizures, etc.) | 2 | 0 | 3 |

Other | 4 | 5 | 3 |

Encountered one or more problems | 38 | 26 | 26 |

None | 60 | 72 | 74 |

No answer | 2 | 3 | 0 |

Table III. FDA-related problems encountered by respondents during the past 12 months. |

Also on the rise were FDA enforcement actions and MDR/user-report problems, which jumped from a mere 1% last year to 6%. According to Ron Johnson, executive vice president at Quintiles Consulting (Rockville, MD), this could be one sign of a worrisome trend: "From the compliance perspective, FDA has taken a number of significant regulatory actions, accompanied by some posturing at the highest levels of the agency about not wanting to be perceived as a paper tiger or as asleep at the wheel. I think we're beginning to see a tightening down. Certainly, the big injunction they took against Abbott is a good example of how aggressive they're being, and I believe there will be others coming down the pike. Things are only going to get worse if additional resources for the agency aren't forthcoming."

PRICES AND PARTNERS

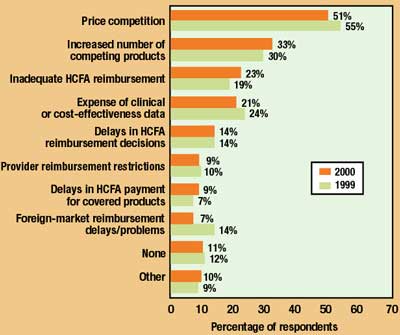

Of course, potential problems with FDA are not the only concerns on the minds of medical device executives. Figure 6 charts those factors that survey participants expect will impose significant difficulties on their near-term product sales. As was the case last year, price competition is far and away the main hardship. "The entire supply chain is being affected by the cost pressures the provider side is experiencing," says Jack Nally. "The hospitals are bleeding money, long-term-care providers are literally bankrupt, and all this is instilling an extreme price consciousness that is continually driving prices downward." Additional pressures, as one respondent noted, come with striving to "meet pricing challenges from third-world manufacturing operations."

Figure 6. Factors expected to impose significant difficulties for product sales in 2000 (multiple answers permitted; 1999 responses also shown).

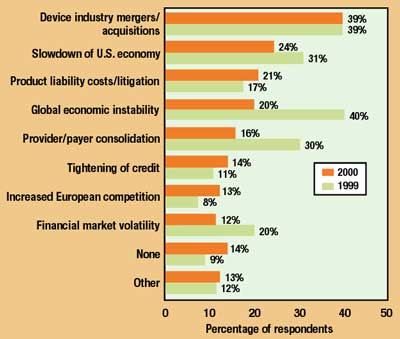

Device industry mergers and acquisitions head the list of more-general economic conditions that respondents think will impact the industry (Figure 7). "The merger and acquisition activities of the larger companies are very much strategically focused," says Richard Cohen, president of The Walden Group Inc. (Franklin Lakes, NJ). "As opposed to diversifying into completely new product areas, they are generally looking to buttress specific niches and maximize their operating leverage by using existing infrastructure to sell related products to the same customers or buying sources." Nally reflects that domestic M&A activity, by reducing the number of competitors in the U.S. market, could have the effect of "opening up the doors for international, foreign-based companies to come in."

Figure 7. Factors expected to significantly impact the medical device industry in 2000 (multiple answers permitted; 1999 responses also shown).

Notable among this year's survey results was the fact that fears about global economic instability were cut in half compared with 1999. This relative contentment was doubtless influenced by the uneventful Y2K transition and the continuing recovery of Asian economies.

CONCLUSION

Be sure to read our companion piece, Survey Respondents Showcase Diverse Industry |

By all accounts, the medical device and diagnostic industry is poised on the brink of a new era of stunning technological advances. Rapid progress in the treatment of major disease states and historic explorations of the nature of heredity are energizing a multitude of companies whose prospects have never looked brighter. Despite concerns over global competition and fears that a dearth of resources at FDA could reencumber the regulatory process, device executives are embracing this vibrant future with confidence and conviction.

Jon Katz is editor of MD&DI.

Top Illustration by Michael Hirano

2000 BUSINESS OUTLOOK REPRINTS |

|---|

Complete survey results are now available in reprint format. The bound volume includes the text and graphics from this issue's summary, along with previously unpublished tabular breakdowns for each question posed in the survey, both by geographic region and by company sales volume. For more information, call 310/445-4200 or visit the Canon Communications Medical Device Bookstore. |

Return to the MDDI March table of contents | Return to the MDDI home page

Copyright ©2000 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like