Medtech Lessons in the Boeing 737 Max Debacle

Medical device manufacturers would be wise to learn from Boeing’s mistakes.

March 25, 2024

If you’ve been following the Boeing 737 Max debacle in recent months, you may have picked up on some key parallels to the medical device industry. And if you haven’t been following this aviation crisis, I highly recommend watching John Oliver’s take on the story.

The lessons that can be gleaned from Boeing’s mistakes serve as critical reminders for medtech.

Lesson 1: It all starts with company culture

Boeing has been widely accused of prioritizing profits over quality and safety, something the company’s own executives have finally admitted.

“For years, we prioritized the movement of the airplane through the factory over getting it done right, and that's got to change,” Boeing CFO Brian West said last week at a Bank of America conference.

This epiphany comes only after a door plug from a new Alaska Airlines 737 Max 9 flew off mid-flight on Jan. 5, prompting a long-overdue crackdown by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

Plastic covers the exterior of the fuselage plug area of Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 Boeing 737-9 MAX in Portland, Oregon after a door-sized section near the rear of the plane blew off 10 minutes after takeoff on Jan. 5, 2024. Image credit: National Transportation Safety Board via Getty Images

The FAA recently completed a six-week audit that found noncompliance issues in Boeing’s manufacturing process control, parts handling and storage, and product control. And, as an Aviation Week article points out, these findings are coupled with recently released results from an expert-panel review of Boeing’s safety culture that U.S. lawmakers ordered in 2020 after two fatal 737 Max crashes in 2018 and 2019.

Fortunately, medtech companies would never put profits over patient safety, right? Oh wait.

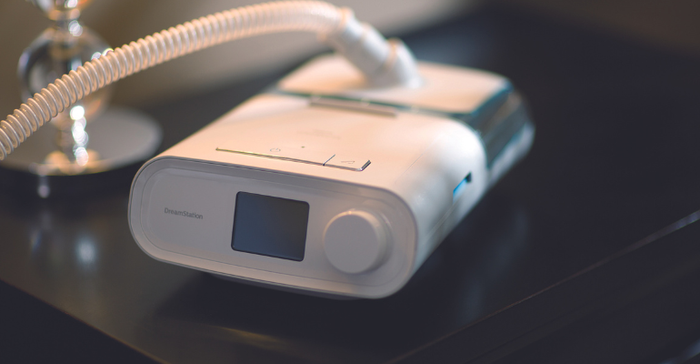

A Philips DreamStation CPAP machine for sleep apnea, part of the company's massive recall initiated in June 2021. Image courtesy of Philips.

We have only to look at the Phillips “Respiratorgate” scandal to see that even medical device manufacturers are prone to letting financial motivations take precedence over patient safety. And that’s just one of many examples, as these types of corporate failures have always plagued the industry. It should go without saying, but the type of fundamental cultural change these situations call for must start at the top.

“These incidents were not just failures of technology; they were, more profoundly, failures of humanity. The loss of 346 lives in these accidents is a somber reminder that behind every flight number and aircraft model is a tapestry of human stories, dreams, and the irreplaceable value of human life,” Alex Soltani, a principal technical program manager at Daugherty Business Solutions, wrote in an article published on LinkedIn.

I was struck by how easily Soltani’s words apply to medtech. Let’s read the last part of that quote again, this time replacing aviation references to medical device references: Behind every medical procedure and medical device is a tapestry of human stories, dreams, and the irreplaceable value of human life.

Lesson 2: Get your supply chain under control

Like the vast majority of medtech companies, Boeing has long suffered from a complex and fragmented supply chain. Using Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner as an example, John Oliver hilariously compares the company’s outsourcing process to using gingerbread kit.

“So, basically, the plan was for Boeing to create the plane the same way someone creates a gingerbread house from a kit. Essentially assembling a bunch of pieces other people made leading to a finished product that, structurally speaking, was always going to be a [expletive] mess.”

The global supply chain crisis that had such profound impacts on the medical device industry during and following the COVID-19 pandemic exposed similar weaknesses. A few years ago, at IME West 2022, I produced a special episode of MD+DI’s Let’s Talk Medtech podcast exploring the weak links in the global supply chain from a medtech perspective.

A big part of the problem was the lack of visibility into the supply chain and the fact that some of the largest medical device OEMs didn’t even know exactly who was in their supply chain. Berardino Baratta of MxD shared a shocking example from a conversation he had at the beginning of the pandemic.

"A senior executive at a very large manufacturer said, ‘yeah, we’re not really super worried about China starting to close down because we don’t buy anything from China.’ Well, five or six levels down, I guarantee you they are," Baratta said. "Well, one of the equipment that they buy, that person's buying something from China.”

Take Medtronic, for example. Speaking at Cowen and Company's annual healthcare conference last year, CFO Karen Parkhill talked about how decentralized Medtronic’s manufacturing and supply chain operations had been.

"We had nine different and distinct supply chain groups," Parkhill said. "We had four different and distinct manufacturing groups, and we've now consolidated that into one each. And we brought in place new leadership from outside of our industry in ops and supply chain."

Lesson 3: Get to the root of the problem

Regardless of how strong your quality control management is, mistakes will happen. What separates good manufacturers from bad is in how mistakes are dealt with.

All too often, manufacturers want to do a patch job on flawed devices, essentially treating the symptoms of a problem without adequate root cause analysis.

Bob Mehta, principal consultant at GMP ISO Expert Services, wrote an article for MD+DI on root cause analysis back in 2013 that holds true today. Mehta points out that the word root in root cause analysis refers to all underlying causes and not just the one that might be obvious.

“That is why it is imperative to be open minded and objective when performing root cause analysis,” Mehta writes.

“Beginning an analysis with a preconceived idea of what appears to be an obvious root cause could result in the incorrect root cause being identified and the wrong correction being implemented.”

Lesson 4: Transparency and oversight cannot be understated

Last year, ProPublica and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette published an investigative report on the Philips Respironics recall. The report accuses the company of hiding its respiratory device problems for more than a decade before initiating its massive 2021 recall of ventilators and sleep apnea machines. Similarly, Boeing is accused of hiding the severity of its problems. I’ve seen too many examples in the past 17 years of medtech companies succumbing to greed and sweeping problems under the rug.

Regulators have a role to play as well. The Government Accountability Office, a congressional watchdog, is currently investigating how FDA tracks warnings about dangerous and recalled medical devices. The probe is in direct response to what some perceive as FDA’s mishandling of the Philips recall. The agency is accused of missing more than one opportunity to mitigate harm to patients using a Philips respiratory machine.

Lesson 5: Don’t shortcut the user training

The geniuses at Boeing apparently decided that pilots didn’t really need to be concerned with how to operate the new 737 Max planes. As Oliver points out, a massive selling point to airlines was that the Max wouldn’t require pilots to be retrained in a flight simulator and failed to tell pilots about a new system on the plane called Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) that is capable of pushing the aircraft’s nose down on its own, and MCAS can be activated by a single sensor.

“Boeing was worried that if they told emphasized MCAS as something new it might require more training. So, it told airlines and regulators that the Max is so similar to the old 737, simulated training wouldn’t be necessary,” Oliver said, going on to reveal that in lieu of costly and time-consuming simulation training, Boeing gave pilots a two-hour iPad training course that never once mentioned MCAS.

“What’s more, it wasn’t in the manual at all unless you count the glossary, which defined the term but didn't explain what it did.”

Boeing’s response to airlines demanding an explanation for why pilots were never told about MCAS was, “we try not to overload the crew with information that’s not necessary.”

This would be like – and this is only hypothetical – Intuitive Surgical rolling out its new da Vinci 5 system and telling hospitals not to worry about training surgeons on the new robot because they already know how to operate the previous da Vinci system.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve asked a medical device company about the learning curve involved with a new surgical device and the executive I’m speaking with has boasted about the device having a very short learning curve, if any at all. While that is a strong selling point for getting physicians to adopt new technologies, perhaps the message should focus more on why the training matters in the first place.

Industries like aviation and medtech make products that have a direct impact on human lives. When problems do arise with airplanes or medical devices, there is no excuse for hiding the severity of the problem, placing profits over people's safety, or failing to conduct adequate root cause analysis to ensure that the right corrections are made.

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)