Trivia Tuesday: In what year did turmoil erupt at the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, costing Director Daniel Schultz his job?

March 28, 2023

The year 2009 is remembered in medtech regulatory circles as the year in which long-simmering turmoil erupted into the open at FDA's Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). It cost Daniel Schultz his job as CDRH director and prompted an external investigation of the 510(k) review program.

Turmoil overtook other areas of CDRH’s jurisdiction as well, such as its checkered enforcement of medical device reporting requirements for ambulatory surgical facilities performing Lasik eye surgery, its handling of medical device recalls, and regulatory standards for laboratory-developed diagnostic tests. Other sources of turmoil that year included the center’s controversial decision not to enforce its Good Laboratory Practice regulation, its final rule on mercury-based dental amalgam, and much more.

Turmoil over 510(k) program

Turmoil actually began in late 2008 when a group of FDA scientists and physicians sent a whistleblower letter to Congress and the incoming Obama administration that has had far-reaching results on the medical device industry.

The group, which became known as The FDA Nine, alleged that in the medical device review process, CDRH managers had "ordered, intimidated, and coerced FDA experts to modify their scientific reviews, conclusions, and recommendations in violation of the law.”

This letter, along with a follow up letter written in January 2009, brought congressional scrutiny that had a significant impact on the 510(k) review process and brought what the device industry largely perceived as negative changes to the 510(k) program.

In May 2009, after new public disclosures from the dissidents implicated a tortured 510(k) clearance that had been granted by Schultz over staff objections to ReGen Biologics for its Menaflex collagen scaffold, Joshua Sharfstein (then-acting commissioner at FDA, who later in the year became principal deputy commissioner, pictured below) ordered a preliminary internal review of the matter. The company had enlisted four New Jersey congressmen to show CDRH their “concern” over the company’s 17 years of efforts through four submissions to demonstrate “substantial equivalence.”

Calling it one of the hardest decisions in his 35-year career, Daniel Schultz resigned as director of CDRH in August 2009. He said his resignation was based on discussions with FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg, MD (pictured below) “and a mutual agreement that my stepping down at this time would be in the best interest of the center and the agency.”

Although AdvaMed and other industry voices made appreciative testimonial statements about his tenure, the activist Project on Government Oversight called Schultz’s resignation a “long-awaited opportunity for openness and reform.”

Schultz was replaced by Jeffrey Shuren. Stung by congressional and media scrutiny, reviewers began to ask more questions about applications, delaying what was once considered a fast-track process. And the medical device industry griped that FDA was killing innovation.

In September 2009, Sharfstein’s review produced a report that found a “definite threat” that the Menaflex review’s integrity had been compromised.

“We found that over the 17-year review history of the [collagen scaffold] device, multiple departures from processes, procedures, and practices occurred,” the report said. “Our ability to assess the effect of these departures on the decision-making process was in many cases undermined by the failure of important decision makers to sufficiently explain and document the bases for their decisions in an administrative record.”

The report went on to say that these actions constituted “a clear deviation from the principles of integrity used in this review and undermines the ability of the agency to counter the suggestion that lobbying on behalf of ReGen affected the decision.”

The report noted that several interviewees, including individuals with 30 years of FDA experience, said the ReGen matter was among the worst experiences in their professional careers, in large part because of the chaotic sense created by persistent pressure on agency decision makers and processes. The pressure came not only from congressional members and the company’s political consultant, but also from FDA leadership—in particular, FDA Commissioner Andrew von Eschenbach (pictured below). Beginning around this time and continuing until the months before clearance of ReGen’s final 510(k) in December 2008, the commissioner became involved in decisions typically committed to the review division or, if escalated, the CDRH director.

Meanwhile, Donna-Bea Tillman, then-director of the office of device evaluation at CDRH, told her staff in September 2009 she was taking immediate steps to strengthen the 510(k) program. In a memo that precipitated industry jitters that 510(k) reviews would be slowed down as CDRH scientists examine them more carefully for signs of “predicate creep,” Tillman said she had already established a center-wide 510(k) working group to look at ways to strengthen the program.

Turmoil over Lasik eye surgery

Patient dissatisfaction with the adverse after-effects of Lasik eye surgery reached a critical tipping point at CDRH in 2009. Complaints included permanent quality of life issues like dry eye, night vision disturbances that prohibit driving, emotional depression, and unemployment. Patients also criticized CDRH for collaborating with an ophthalmologists’ organization in dealing with these issues.

A potent Internet network of injured Lasik patients bombarded the agency with criticisms, petitions, and complaints until CDRH sent a letter in May to eye care professionals informing them about proper advertising and promotion practices related to the procedure. The agency acknowledged that eye care professionals’ advertisements for Lasik procedures failed to inform consumers of the indications, limitations, and risks associated with the procedure.

FDA vigorously denied the injured patients’ charges that it has failed to follow up on the April 2008 Lasik advisory panel hearing. Among its follow-ups, FDA cited developing an FDA Lasik website; updating Lasik-related information in the SightNet program for health professionals to emphasize that halos, glare, night vision, and dry eye problems from Lasik should be reported to the agency; and developing a patient information card with the American Academy of Ophthalmology to help Lasik doctors calculate the lens implant power should patients need cataract surgery in the future. FDA said it had also recognized a recent Lasik standard from the American National Standards Institute and opened a public docket for Lasik so that any interested person could submit comments.

None of this, apparently, was enough to placate the patients’ network. It kept up the pressure until, in October 2009, FDA sent warning letters to 17 Lasik ambulatory surgical centers after inspections revealed inadequate systems for reporting adverse events related to the vision correction surgery. The letters did not identify problems with the devices themselves, but cited the recipients for failing to develop, maintain, and implement written medical device reporting procedures.

FDA also launched a collaborative study with the National Eye Institute and the U.S. Department of Defense to examine the potential impact on quality of life.

Unfortunately, regulatory oversight of Lasik and informed consent requirements continue to be a thorny issue to this day. Patients considering Lasik eye surgery need to be better informed of the risks associated with the procedure, according to an FDA draft guidance published in 2022. Suffice is to say the guidance didn't go over well with eye surgeons and medical device manufacturers.

The 29-page document focuses on the risks associated with Lasik and notes that a few patients have become severely depressed – even suicidal – after experiencing complications from the surgery. People with diabetes and certain other chronic conditions may have a higher risk for poor Lasik outcomes, according to the document. Among the agency’s recommendations is a “decision checklist” describing Lasik surgery, highlighting that the corneal tissue is “vaporized” during the procedure and corneal nerves may never recover from incisions, resulting in dry eyes and, in rare cases, chronic pain. This decision checklist proposal has many in the industry fired up. They claim that such a checklist is regulatory overreach and would interfere with the doctor-patient discussion.

Turmoil over CDRH's response to recalls

Turmoil also erupted in 2009 over the fact that CDRH struggled to promptly report medical device recalls. The center's public postings tended to lag behind drug recall postings by months and sometimes years.

In March 2009, Sidney Wolfe, then-director of Public Citizen Health Research Group, began a series of well-publicized complaints about CDRH’s tardiness in posting recalls. First, he complained, the center took nearly three months to tell the public about a class I Covidien recall of Nellcor’s Shiley 3.0 PED tracheostomy tube.

“Often the public does not become aware of a problem with a medical device until well after a company has already begun the recall process,” Wolfe said.

The next day, he asked why CDRH had waited for 47 days to classify as class I a recall of Baxter's Colleague infusion pumps after the company warned users about serious problems that could interrupt therapy. And the day after that, Wolfe wanted to know why CDRH had not yet announced Welch Allyn’s class I recall the previous month of 14,054 automatic external defibrillators (AEDs). In his third letter in as many days to FDA Acting Commissioner Frank Torti, Wolfe said the Welch Allyn recall was the largest of six recalls of “these dangerously problematic devices to date.”

"The recall once again makes it clear that the entire category of AEDs, a class III medical device, is insufficiently regulated by FDA," Wolfe said.

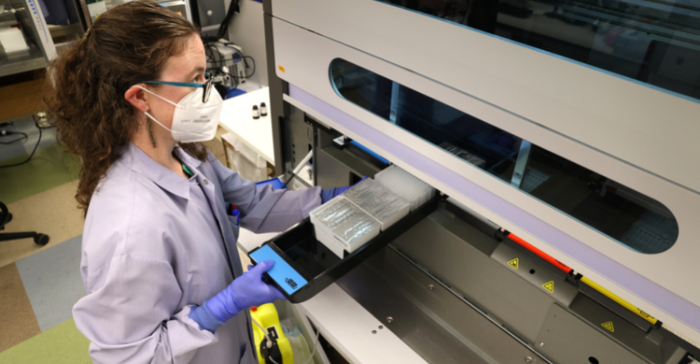

Turmoil over LDT regulation

Controversy over the bifurcated regulation of laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) increased in 2009 amid indications that new leadership at FDA may be less inclined than its predecessors to tolerate the status quo. Confusion over the extent of FDA regulatory authority came up several years before when the agency said it retained authority to regulate in vitro diagnostic multivariate index assays. The agency took several opportunities in 2009 to send speakers out to industry meetings to say that, contrary to speculation, it still intends to regulate LDTs regulated under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The controversy gained momentum in December 2008 when Genentech filed a citizen petition asking FDA to regulate all LDTs, saying that this would provide greater consistency in FDA enforcement and better protect the public health. The Coalition for 21st Century Medicine, which represents diagnostics firms, clinical laboratories, researchers, physicians, venture capitalists, and patient advocacy groups, had said that if FDA agrees with Genentech, it would result in delayed introduction of critically needed diagnostic tests. The group also said that taking Genentech’s position would impose high costs on laboratories and put significant pressure on FDA’s budget and personnel.

However, Alberto Gutierrez, then-deputy director of CDRH's Office of In Vitro Diagnostic Device Evaluation and Safety, said in August 2009 that LDTs are often legally marketed for wider use without being subjected to the rigors of the FDA approval process. This “two-tier” approval system presented some unfortunate gaps in regulatory oversight, he said. For example, FDA requires a research phase for approvals, CLIA does not; FDA requires analytical validations, while CLIA does not; FDA requires clinical validations, but CLIA does not. In addition, FDA requires reports on adverse events, but there is no such requirement for CLIA-approved tests, and no system in place for receiving or analyzing adverse-event reports.

Since 1997, FDA has attempted to partially close the regulatory space that exists between laboratory tests that have been marketed through the FDA process and those that have come to market under CLIA rules.

Then in September 2009, CDRH acting director of chemistry and toxicology devices Courtney Harper amplified Gutierrez’s message at a Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society meeting. She said that CMS-regulated LDTs were tolerated under FDA “enforcement discretion.” They “present risks to patients,” she said, defining them as tests that have been fully developed in a single laboratory for use only in that laboratory, and that have no premarket review, no independent research basis, and no requirement for clinical validity.

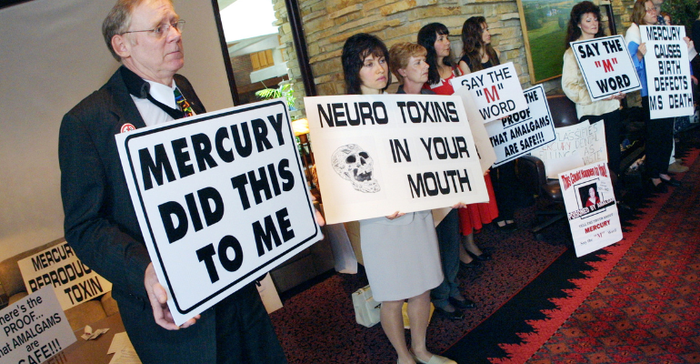

Turmoil over mercury-based dental amalgam regulation

In August 2009, FDA published a final rule reclassifying mercury-based dental amalgam as a class II device. This action shocked many dental and toxicology experts, who quickly submitted two petitions seeking reconsideration.

Two experts on mercury amalgams criticized the final rule’s literature-review and procedural foundations, saying that they upheld prior controversial agency assertions that continued use of mercury in amalgams is safe, except for allergic patients. In addition, dentists had long been retreating from amalgam in favor of safer, less-durable, and more-expensive alternatives.

David Kennedy, a preventive dentist and international lecturer on toxicology and restorative dentistry, told MD+DI in 2009 he had read the final rule in its entirety and found numerous errors in FDA's assumptions. In particular, he said, the preamble to the rule minimized the effect of mercury amalgams on children between the ages of two and seven as measured clinically in urine. He said the preamble discounted the significance of clinical studies that showed progressively less mercury leaking into the urine of children, particularly boys, year to year. “If less and less is leaking into urine, it’s obviously accumulating in the body,” Kennedy said.

Kennedy also faulted FDA for adhering to the agency’s 2006 white paper declaring mercury amalgams safe, even after it was soundly rejected by a joint meeting of its Dental Products Panel and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee. The second expert criticism of FDA’s rule came from University of Washington’s James Woods. The research professor said that the rule’s preamble had erroneously used three out of nine citations to his publications on the effects of mercury amalgams in humans.

All this and more had little effect on FDA’s public face that year.

“The FDA does not agree with the characterizations of its rulemaking,” said Mary Long, an agency spokesperson at that time. “The agency’s findings and conclusions are based on an extensive review and analysis of the scientific data pertaining to potential adverse health effects from exposure to mercury vapor from dental amalgams in the general population and in sensitive subpopulations. The FDA believes its rulemaking is in compliance with the Administrative Procedures Act.”

Moms Against Mercury national counsel Charles Brown then mounted a trenchant campaign against FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg for having a conflict of interest on amalgam based on prior stockholdings in and employment by a major amalgam shipper. This campaign was also waged against Sharfstein for being responsible, after Hamburg’s recusal, for such a scientifically flawed rule. This campaign consisted of a flood of carefully orchestrated e-mails to both officials from members of Brown’s 5,000-strong network of people opposed to mercury amalgam.

In 2010, CDRH admitted it was wrong about the mercury amalgam controversy. The controversy was far from over, however. In 2015 FDA denied multiple petitions that sought to ban mercury-based dental amalgams.

Check back next week for a new Trivia Tuesday question on our home page and test your knowledge about the medical device and diagnostics industry!

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like