It’s all in the Timing. If you are a business leader at a company that sells active or powered medical devices, the looming question for the past several years has been “When do I certify my medical devices to IEC 60601-1:2005 also known as the third edition?” This is a complicated question, with many variables to consider before choosing a path appropriate for your business including the following:

April 14, 2011

How long is the development cycle of my medical device?

What global markets am I targeting for my medical device?

What is the average product life of my medical devices?

How much will it cost to update my files?

Are the particular standards affecting my medical device mapped or harmonized to the third edition?

What resources can I commit to modifying my device?

What are the consequences to my bottom line if I do not certify?

Although this list covers some of the major considerations, there are many other factors that can influence the decision and timing for implementing a third edition strategy. All are worth considering as a firm analyzes the costs versus benefits for the organization.

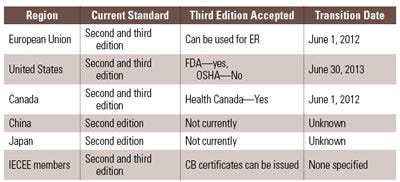

As new jurisdictions adopt the third edition, the evolution of a global strategy for 60601-1 third edition must keep pace with the changing regulatory landscape. Indeed, acceptance of 60601-1 third edition is coming and though it has taken what seems to be a long time to reach the current limited recognition (the standard has been published since 2005), the adoption and application dates are rapidly approaching. FDA, Health Canada, and the European Union have published their acceptance and transition timing. Now is the time to take action.

The State of the Standard

Looking at the current state of regulatory agencies, as they relate to 60601-1 third edition, there are some differences within the rollout plans for adoption and mandatory applications of the standard. A few markets are experiencing transition periods. Canada was the first country to publish a transition period and also the first to reschedule that transition period. These changes contribute to the confusion for companies that don’t know when to begin complying with the third edition. Health Canada originally stated that for new product submissions or for reissuance of certificates, proof of compliance with the third edition of IEC 60601-1 was required as of December 15, 2008. When industry and certification bodies alike expressed concern, it became apparent that the transition period would be very difficult. After consideration of the industry’s and certification bodies’ feedback, Health Canada extended the transition period to June 1, 2012. Currently, companies are able to obtain new product certificates and reissuance of product certificates in Canada by demonstrating compliance with IEC 60601-1 second edition in conjunction with the appropriate and applicable collateral and particular standards. After May 31, 2012, all manufacturers seeking product certificates and or reissuance of product certificates will be required to use IEC 60601-1 3rd edition before they can legally sell their devices in Canada.1

|

Table 1. Transition times and acceptance of 60601-1 third edition. |

On June 10, 2010, FDA announced that it had adopted and recognized ANSI/AAMI 60601-1:2005 and established June 1, 2013 as the mandatory transition date to ANSI/AAMI 60601-1:2005. This means FDA will accept declarations of conformity in support of premarket submissions to IEC 60601-1 second edition until June 30, 2013. After the transition period, declarations of conformity to the second edition of 60601-1 will not be accepted.2 It is important to note that OSHA has not adopted ANSI/AAMI 60601-1:2005 as a consensus or recognized standard and as of the date of publication, is reviewing the document.3 Many expect that OSHA will adopt this standard and provide for certification with this document through the NRTL program consistent with the timelines associated with the FDA transition period. In addition to the OSHA consideration, NFPA 99, the standard that governs healthcare facilities, is in the process of aligning with IEC 60601-1 third edition.4 The hope for medical companies looking to sell products in the United States is for this standard to be aligned with the transition period noted by FDA. Otherwise, it is possible that these companies will be required to maintain second edition for OSHA and third edition for FDA.

Under the Medical Devices Directive 93/42/EEC, the European Union attaches the presumption of conformity to a product when the product is evaluated to and complies with a harmonized standard. To satisfy this presumption of conformity, an active medical device can be evaluated to either version of the IEC 60601-1 standard along with the applicable collateral and particular standards that align with these versions. This presumption of conformity extends to both versions until the date of withdrawal (DOW) of EN 60601-1: 1990 (i.e., IEC 60601 second edition). Of note, the EU has revised the original DOW for EN 60601-1: 1990 in much the way Canada revised their mandate for third edition. The new DOW for EN 60601-1: 1990 is currently set at June 1, 2012, which aligns with the date fixed by HC. This means that manufacturers of devices put into service, sold or otherwise on the European Market after June 1, 2012 must ensure that the device complies with EN 60601-1:2006 (the third edition) prior to applying the CE Mark. Devices that do not comply with the third edition risk long delays as the devices may be held up at customs.5

The frequent changes to the withdrawal and mandatory use dates have raised a lot of questions and doubt when it comes to third edition strategies. Decisions that directly affect product sales, including which product lines to redesign and to let pass into obsolescence are impacted by this perceived uncertainty. Prudent business leaders must have all the information available to make these decisions.

How do you ensure you have all the facts you need?

Do you understand what the changes to the standard mean to your business?

Have you done the analysis of how your product and processes will perform in the new certification paradigm?

Have you considered who, within your organization, should be making these decisions?

While there are many resources to tap into to answer these business-critical questions, in matters involving regulatory affairs, it is often important to take lessons from history.

A Historical Perspective: the Challenges of the MDD Transition

In 1993, the European Commission (EC) published 93/42/EEC or the Medical Devices Directive (MDD).. The European Union’s goals were to develop regulations for medical device market access. Why the compare the medical device directive to the third edition? First there is an equivalent level of complexity associated with the third edition processes and design considerations as there was with the implementation of the MDD. Both the MDD and the third edition are paradigm shifting, have specific elements focused on products, have a high degree of process based elements affecting the device’s design and have a similar transition period. Second, the MDD implementation provides valuable lessons on how to manage timing, new process implementation, and transition details.

Within the framework of the MDD, the EU introduced several concepts that many medical device manufacturers were not initially prepared to deal with. Two key items were the technical file (product specific element), and registering a quality system in compliance with EN/ISO 46001, now EN/ISO 13485 (process specific elements). Device manufacturers were generally comfortable with design history files for their 510(k) and FDA QSRs; however, few were initially prepared for the concept of the technical file and quality system audited by a Notified Body. These concepts are now commonplace and well understood. In fact, today some device manufacturers choose to use the EU for their initial launch because these factors are so well understood and consistently applied. However, the evolution of the industry to arrive at this point of comfort and common place with these elements was challenging and in some instances painful and costly, with some devices being taken off the market under the authority of Article 8 of the MDD. Article 8 of the MDD, known as the Safeguard Clause, provides member states with the authority to restrict or prohibit placement or withdraw devices for failure of the manufacturer to meet the essential requirements, for incorrect application of the standards referenced in Article 5, or for shortcomings in the standards themselves.6

As part of the development of this article, the authors asked several medical devices manufactures, who asked to remain anonymous, if given the opportunity, what would they change about their organization’s strategy and implementation during their company’s transition to meet the requirements in the MDD. Universally, they responded that they would have chosen not to have delayed, ignored, or thought that the MDD could not apply to their products.

Moreover, if given the opportunity to travel back in time, those interviewed would have made greater initial efforts to understand the requirement and comply with the requirement. Among the several examples of their experience with the MDD transition, many had challenges with the registration of their quality system. The following section explores a company’s experience with MDD and draws parallels in testing to illuminate some of the challenges that companies could face with the third edition transition.

Lessons Learned During the MDD Transition

In the early days of MDD, an engineering and compliance team reviewed a company product that had been marketed globally for several years. The product was, at that point, not considered a true medical device. Rather it was a cathode ray tube monitor that aided in a diagnosis and was considered a laboratory device. Today industry is fairly comfortable with its understanding of the MDD and confident that devices that aid in diagnosis are considered medical devices under the regulatory scheme.

For this particular device, the team had reviewed the MDD, followed the applicable rules of the directive within Annex IX and determined that their device was within the scope of the MDD. The challenge was convincing their management team.

Forty percent of the company’s revenues were driven from sales of the product in the European Union. The company had been producing and selling the device for many years with no problems, no adverse incidents, and no recalls. Management was unconvinced as to why that would change. Further, the changes the engineering team proposed would affect the business, as follows:

The additional burden was not going to make their product safer.

The design changes proposed could take production off line, therefore reducing revenues.

The potential for submitting to FDA due to the change in technology and the lead time required for that process would also reduce revenues.

The added layer of regulation was going to make their product more expensive, increasing per-unit costs.

The engineers were unable to convince management of the potential pitfalls and how those pitfalls would negatively impact the business’ bottom line.

One area that was universally misunderstood by the management team and highlights the associated challenges was the electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) requirement. EMC compliance is part of the essential requirements for the MDD (a product specific requirement that has proven challenging for manufacturers to comply with).

The engineering team felt that the unshielded CRT monitor product would not comply with the EMC requirements and limits. The team looked more closely at the mitigation required and understood that this was something that needed to be dealt with immediately, before the inevitable need for testing. When the management team reviewed the engineering report no action was taken because, the management team was still not convinced that the MDD was applicable to their device.

Throughout the course of the next two years, the engineering and compliance team engaged in many meetings and strategic planning session for compliance and finally brought on board an expert consultant to help develop the internal messaging for their compliance plan. These efforts yielded an approach that the management team understood was tied to the bottom line and communicated the importance of the changes and challenges that their organization needed to meet. That was the good news. The bad news was this process took more than two years to accomplish and the organization was in a position of having numerous actions to take in a very short period of time. The organization was painfully aware of the need to comply with the Directive and had approximately seven months remaining in the transition period in which to do it. With that knowledge, the management team authorized the engineering team to spend the money to implement the compliance strategy they had been developing.

What ensued can only be described as a frantic attempt to meet all the essential requirements without losing the ability to market their products in Europe. At every turn the organization faced design challenges, supply challenges, and lab testing time challenges all compounded by the compressed schedule they had to work from. This organization found that they were competing with many other organizations in a similar situation.

The first time through the labs for testing was an abysmal failure. Not only had the device failed, the organization spent an estimated 40–50% premium for the testing time. Independent laboratories were running three shifts a day to try and keep up with the demand. They were scheduling testing time months in advance and for every week reduction in the schedule the labs were charging a premium, there was just not enough testing resources in the lab industry to keep up with the demand for testing. With the first round of results in place the engineering team determined that the CRT monitor would not pass without significant modification or replacement. Several iterations of testing later, it was determined that a combination of pre- and postproduction processes was the practical solution to bring the monitor into compliance. These special processes on the monitor ultimately brought the device into compliance however it was at a significant expense; they would add an additional 5% to the per unit cost of this product, several rounds of iterative testing enduring the 40–50% premium testing expense, and adding an additional two to three weeks lead time for each product as a result of the new processes for compliance.

Conclusion

Today medical device firms are multitask environments and less time is spent on truly understanding changes in the regulatory requirements. Often manufacturers go through the motions of compliance without understanding the relevance to their company and their company’s products. The requirements for certification and regulatory approval are increasingly linked together and in a constant state of evolution.

It is this lack of understanding as we saw in our example above that creates many challenges, some more costly than others. As we move forward into the IEC 60601-1 third edition era, although this standard revision may appear small it can have a profound effect on how device manufacturers bring their product to markets. It is incumbent on device manufacturers to take a step back and gain that understanding. There are many resources in the market as well as numerous certification agencies that can help. Become informed and make good business decisions on which of your products you will upgrade to third edition compliance and which you will let pass into obsolescence. Don’t wait until it is too late to make the necessary changes.

References

1. "Date for Transition from the Second to the Third Editions of IEC 60601-1 and IEC 60601-1-2 on the Health Canada's List of Recognized Standards," Health Canada; available from Internet: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/md-im/standards-normes/notice_iec_60601_avis-eng.php.

2. "Recognized Consensus Standards," FDA; available from Internet: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfstandards/detail.cfm?id=28193.

3. "List of Test Standards Recognized - through 7/1/2009," OSHA; available from Internet: http://www.osha.gov/dts/otpca/nrtl/allstds.html.

4. "Standard for Healthcare Facilities," NFPA; available from Internet: http://www.nfpa.org/aboutthecodes/AboutTheCodes.asp?DocNum=99&cookie%5Ftest=1.

5. "EN 60601-1:2006," CENELEC; available from Internet: http://www.cenelec.eu/dyn/www/f?p=104:110:5912023481286045::::FSP_PROJECT,FSP_LANG_ID:15126,25

6. 93/42/EEC Medical Devices Directive.

Joseph E. Madden is Sales Manager Americas at Underwriters Laboratories Health Sciences

Joseph E. Madden is Sales Manager Americas at Underwriters Laboratories Health Sciences

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like