Take it from Advanced Bionics. If you’re going to use CISPR 11 to support findings in pre-market applications, it better be correct.

March 6, 2023

If anyone thinks that the International Special Committee on Radio Interference (CISPR) standards are not relevant when it comes to United States product marketing, they should think again. On December 20, 2022, the Department of Justice (DOJ) announced a $12 million monetary settlement with Advanced Bionics, a manufacturer of FDA-approved cochlear implants, for falsely claiming that one of its products complied with CISPR 11 standards. Interestingly, CISPR 11 compliance is not a legal prerequisite for FDA approval or for US marketing of medical devices generally, including cochlear implants. So how does DOJ justify a monetary penalty for failure to comply with a voluntary CISPR standard?

First, a little background. To access the US healthcare market, an electronic medical device manufacturer must demonstrate compliance with a number of technical standards including, among others, the electromagnetic compatibility limits set forth in the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) Part 15 and Part 18 rules. To access most foreign healthcare markets, manufacturers must demonstrate electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) compliance with CISPR 11 limits that are similar, but not identical to, FCC rules. Typically, for purposes of worldwide marketing, healthcare manufacturers will “kill two birds with one stone” by testing for both FCC and CISPR compliance and including both sets of test reports in their product marketing applications.

In the US, medical devices are approved — or cleared — for marketing based on the truth and accuracy of information submitted to FDA. Similarly, the reimbursement for medical devices under federal healthcare programs (Medicare, Medicaid, Veteran’s Health, etc.), depends on the same truth and accuracy of this information. Thus, if any technical data in an FDA application is determined to be false, a claim for reimbursement would also be false and, if made knowingly, would violate the US False Claims Act (FCA), set forth in 31 U.S.C. § 3729. And FCA violations for medical products can be quite expensive.

Under US law, a “false claimant” is anyone who seeks or obtains a reimbursement from a federal healthcare agency for a medical device approved by FDA based on false test data. The monetary penalty for an FCA violation includes both civil penalties and triple damages for financial injuries — like payments for unlawful devices — sustained by the federal government. Importantly, the FCA allows a private party — known as qui tam relator — to bring a civil action on behalf of the federal government and share in up to 25% of any damages awarded. More important, the qui tam plaintiff gets to share in any damage award even if DOJ takes over prosecution of the case, as it is required to do in various circumstances. Thus, by design, the FCA incentivizes whistleblowers to file qui tam suits against drug and medical device manufacturers whose products were approved based on false data or were marketed for unapproved uses.

In the cochlear implant case, Advance Bionics submitted a pre-market application to FDA showing both FCC and CISPR 11 compliance. Although CISPR 11 compliance is not required for US marketing, positive test results were used to support a finding of safety and efficacy required for FDA approval. According to the FCA complaint, Advance Bionics’ test engineers knowingly rigged a worst-case EMC test procedure to falsely demonstrate CISPR 11 compliance. FCC compliance was not at issue in the case and there was no evidence of any implant causing actual or threatened radiofrequency interference. Nonetheless, DOJ concluded that the knowing submission of false CISPR 11 test data to support an FDA determination of safety and efficacy for the implant was sufficient evidence to sustain an FCA action for triple damages. Hence, the $12 million settlement award that was presumably shared with the whistleblower, in this case a disgruntled test engineer.

It is significant to note that the FCA test for “knowingly” does not require the person submitting the false reimbursement claim to have actual knowledge that the claim is false. A person can be liable for acting in reckless disregard or deliberate ignorance of the truth or falsity of such information. The broad sweep of this statute, coupled with its unique qui tam incentives, renders the FCA an effective tool for ferreting out “false claimants” for medical reimbursements even when such falsity involves submissions, such as CISPR 11, that are not technically required for US marketing.

Let this case be a warning to electronic medical device manufacturers seeking access to US markets. If you claim CISPR 11 compliance to a federal authority, you better be correct.

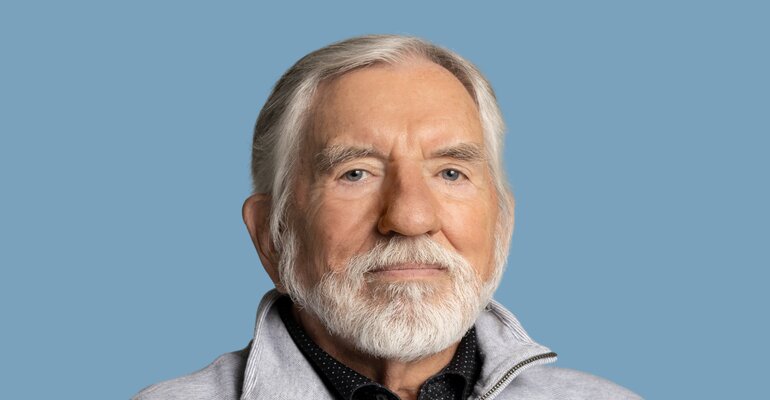

Terry Mahn is a senior principal with Fish & Richardson and leader of the firm’s regulatory & government affairs practice group. His practice is primarily before the US Federal Communications Commission and Food and Drug Administration with emphasis on complex product authorizations. He is an active member of the International Electrochemical Commission/International Special Committee on Radio Interference and is the US technical advisor to CISPR Subcommittee B in charge of developing international radiofrequency interference standards for industrial, scientific, and medical devices. He also represents the American National Standards Institute C63 Committee before the FCC and other federal agencies on various radiofrequency interference matters involving digital devices and many types of RF emitters.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like