December 1, 2015

Synthetic biologists continue to advance a molecular editing system known as CRISPR that provides the opportunity to edit the DNA of living cells with unprecedented precision. While the technology's ability to safely alter human DNA has yet to be proven, MIT scientists claim that they've all but removed potential errors from the technology.

Kristopher Sturgis

|

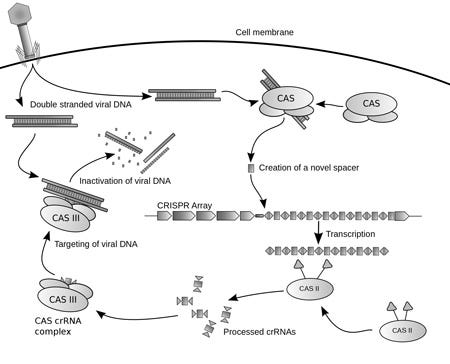

Diagram of the CRISPR prokaryotic viral defense mechanism from Wikipedia |

In April 2015, Chinese scientists announced that they were the first researchers to use the CRISPR gene editing software to modify human embryos. While reports of "designer babies" inevitably followed, the project was beset with significant accuracy problems. Only four of the 54 embryos modified in the experiment demonstrated the correct genetic modifications and, of those four, segments of their DNA had been inadvertently modified. As the scientists explain in an abstract of a paper published in Protein & Cell, there is a "pressing need to further improve the fidelity and specificity of the CRISPR/Cas9 platform" before it is ready for clinical applications.

Now, MIT scientists are claiming that they have all but eliminated "off-target" editing errors, potentially clearing the way to successfully use CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) to modify human DNA.

The technology, which is fast, relatively inexpensive to use, is sparking a moral debate about the virtues and potential foibles of editing human DNA. This week, hundreds of researchers, politicians, and the president's science adviser met in Washington D.C. to discuss the ramifications of the technology. Editing human DNA--even accurately--could potentially cause unintended side effects that could be hereditary.

Still, don't expect to see designer babies any time soon. One of the pioneers of CRISPR, Jennifer Doudna, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley, was quoted as saying in the Washington Post that scientists "don't understand enough yet about the human genome, and how genes interact, and which genes give rise to certain traits to edit for human enhancement today."

The potential applications of the technology, however, are vast. Researchers have already used the technique in animal embryos, as well as human stem and immune cells. Other applications include genetically modifying crops and curing diseases like AIDS, and preventing a wide range of hereditary diseases like cystic fibrosis, sickle-cell anemia, Huntington's disease, or muscular dystrophy through "germ-line" editing.

"Germ-line" editing is so-called because it involves altering the DNA in sperm, eggs, or embryos.

There have been a growing number of concerns raised within the genomic research community, both from an ethical and safety standpoint. Even the National Institutes of Health issued a statement earlier this year refusing to fund any gene-editing technologies in human embryo citing safety and ethical concerns, as well as a lack of medical applications that would justify such an endeavor. Other critics have mentioned the alarmingly possibility of gene-editing techniques to be abused for eugenic purposes.

Learn more about medical technology trends at BIOMEDevice San Jose, December 2-3. |

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to our daily e-newsletter.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like