WASHINGTON WRAP-UP

May 1, 2009

|

Behold the new broom that sweeps clean! It will take weeks and months to be fully felt, but a housecleaning of unprecedented proportions is under way at FDA under the expected dual leadership of Margaret Hamburg as commissioner and Joshua Sharfstein as her principal deputy.

Industry observers expect the new FDA leadership to sweep aside the agency's entrenched way of doing business. That process gave product sponsors a high level of influence over the way their products are dealt with by agency review divisions. The dubious agency-industry partnership that sped new health therapies to market was a legacy of user-fee legislation, which may itself be revisited as well.

For now, however, the new team at FDA will focus on the culture and transparency issues that are part of that partnership legacy. Among these is the alleged voluntary eagerness of managers to treat fee-paying sponsors as FDA clients who deserve a “customer is always right” attitude when they submit products for premarket review.

An extreme manifestation of this culture was seen in the spontaneous public complaints from dissident CDRH physicians and scientists. They expressed that their superiors, including Schultz, had overridden their decisions and recommendations at the behest of product sponsors.

On top of this, consumer advocacy group Public Citizen's Sidney Wolfe alleged in March that CDRH took 47 days to issue a Class 1 recall classification for a line of pumps manufactured by Baxter Healthcare. This was after Baxter told users of its Colleague volumetric intravenous infusion pumps in January that “an interruption of therapy may lead to serious injury and/or death.”

Just two days before the Class 1 recall classification, CDRH had blandly announced a similar finding concerning Nellcor's Shiley 3.0 PED tracheostomy tubes—four months after its first awareness of Class 1–worthy defects.

Why so slow? Device recall notices have been chronically late, sometimes by a year or more, in reaching the public since the Medical Device Amendments of 1976 were enacted.

Slow reactivity to public health hazards is only one of the center's problems. Another recently reported problem is its perceived chumminess with certain—but not all—of the companies it is supposed to be regulating at arm's length.

In early March, another example of well-documented and corrupted approval processes at CDRH came to light. Allegations surfaced that Hackensack, NJ–based ReGen Biologics had pressured the center through its congressional contacts to steer its collagen scaffold, which is used for meniscus knee repair, away from the more rigorous premarket approval (PMA) review and into the 510(k) process.

Numerous objections were voiced from CDRH review staff that the device was proposed for a newer intended use (heavy loadbearing) rather than the predicate shoulder meshes (light or nonloadbearing) that the company had cited. But ReGen turned to four lawmakers from New Jersey to turn up the heat on the agency and overturn its 510(k) denial. Eventually, at ReGen's request, then-commissioner Andrew von Eschenbach asked Schultz to review the case and later decided that the 510(k) process would be acceptable. And von Eschenbach agreed to hold an expert advisory committee meeting with ReGen-approved membership to gain the panel's concurrence. (Read more about ReGen's below in “Special Treatment for ReGen”).

During the advisory committee review, FDA reviewers who objected to the 510(k) were not allowed to speak due to a ReGen allegation that they were biased against the company. Instead, CDRH Office of Science and Engineering Laboratories director Larry Kessler, who has since retired from the agency, summed up the FDA review on the device. Kessler said the review could not find a predicate device and disagreed with ReGen's assertions that its meniscus repair scaffold was equivalent to a mesh used in rotator cuff surgeries, according to the transcript. He said ReGen's device and its new intended use presented certain kinds of clinical situations that might be of concern and, consequently, the agency would like to see a lot of clinical data under the PMA process to establish its effectiveness and safety.

In summarizing FDA's concerns to the panel, Kessler said that although the collagen scaffold is designed to be replaced by meniscal tissue, “we have seen no evidence that the tissue replacement for the collagen scaffold is meniscus-type. We don't know that it's Type 1 or 2 collagen, no evidence of that.” On the safety side, he said the collagen scaffold treatment group had some significant, device-related adverse events. He also expressed concern on six explants with this group that “suggest mechanical failures of the device are possible.” On the effectiveness side, he said ReGen's device did not attain significance compared with the partial meniscectomy group in any primary endpoint, adding that “we see no evidence of clinical effectiveness.”

|

Many observers hope that Margaret Hamburg will help transform the agency and help it regain public credibility. |

Kessler's concerns echoed a memo written by CDRH review team leader John Goode. This documented how both von Eschenbach and Schultz intervened after the company appealed earlier 510(k) rejections. It appears that Schultz was instrumental in coaxing the company to resubmit a 510(k) for a narrower intended use (patients with chronic meniscus tears). That submission would rely on data from a journal study to show equivalence to the predicate device used in rotator cuff surgeries. Goode again found the device not substantially equivalent and cited concerns that the company was seeking to broaden its intended use during the course of the review.

During an open public comment period at the panel meeting, Public Citizen's Jonas Hines recommended that FDA not approve the device on the grounds that a clinical trial conducted by the company conclusively proved that the device had no clinical benefit. Instead of data based on clinical trials, the company submitted laboratory test results that did not involve testing on humans, he said. The group felt the device should have been reviewed under the PMA process.

In voting, the panel, composed of special experts requested by ReGen, told FDA that there was evidence of some soft tissue in-growth. However, they said, it was not clear whether the device was actually functioning like a meniscus, and any failure appeared to be no different than a simple meniscal tear. Thus, ReGen's device did not appear to carry any additional harm or risk. Several panel members said it was questionable that ReGen's device was substantially equivalent to the predicate device because there really wasn't an adequate predicate device with which to compare it.

|

Although Joshua Sharfstein has been selected as Hamburg's deputy at FDA, he is currently the agency's acting commissioner. |

Despite the review concerns and some mixed panel member comments about not really having an adequate predicate device for comparison, Schultz overrode all of this and issued ReGen's final clearance on December 18. He declined my request for comment.

Public Citizen made predictable capital out of these disclosures. Most patients will never know, it said in an e-mail, that ReGen's device reached the market “only through the sponsor's cunning manipulation of the regulatory process, aided and abetted by FDA, leading to approval through this less-rigorous pathway. Until the agency puts itself back on a secure scientific footing, the public will continue to put little stock in its approval decisions.”

Senate Finance Committee ranking member and frequent FDA critic Charles Grassley (R–IA) has requested information from FDA and ReGen about their communication during the review process. He said copies of e-mails he has already received “make it look like the device maker was calling the shots and FDA was going out of its way to accommodate the company…I hope this new example helps compel the new administration to name an FDA commissioner committed to independent, scientific assessment on behalf of consumers.” He continued: “Congress needs to do its part, too, but the culture of the agency is set from the top down, and the next commissioner needs to be a reformer.”

In addition to compliance and approval issues, CDRH, like other FDA centers, seems to have a problem of ingrained review staff bias. All of these examples may be seen as symptoms of systemic dysfunction that is beyond the capacity of any single center director or even commissioner to fix. Consequently, because commissioners and center directors are actually more ambassadors than practical managers like their private-sector counterparts, all have consistently looked the other way. This exacerbates CDRH's underlying root problems.

Ironically, this behavior is exactly the opposite of what FDA expects of companies when its inspectors find systemic data quality or manufacturing problems. The implicit hypocrisy of this situation—do as I say, not as I do—is intolerable and must end. Of course, the full quality of what CDRH management does has become harder than ever to assess. Physical security of FDA buildings keeps the prying media and consumer activists out unless under escort; congressional and media communications are carefully managed, channeled, filtered, and often simply ignored for the best possible effect; and the only reliable insights seem to come under discovery during federal court litigation. But that path is too expensive for most inquiring minds.

The best start on all this reform will likely be the new Hamburg-Sharfstein broom that, if confirmed, sweeps clean—starting at the top.

ReGen was afforded special treatment for its knee device, presumably due to its Capitol Hill inquiries, according to an e-mail exchange leaked to the news media by dissident center staff. In a draft letter to ReGen, Andrew von Eschenbach wrote the following:

FDA has welcomed your input into the structure and composition of this advisory committee in an effort to assure you of its effective and impartial deliberations. We have invited six temporary voting members to participate in the advisory committee, five of whom, per your request, have sports medicine backgrounds. In selecting these temporary voting members, we have been mindful of the criteria you sent us regarding the types of experts that you believe are best qualified to evaluate the CS Scaffold. This is a large number of temporary voting members; because of scheduling constraints and roster limitations, only two of the participants will be permanent members of the committee.

The draft was reviewed by FDA acting chief counsel Jeff Senger, who questioned the statement: “FDA has welcomed your input into the structure and composition of this advisory committee….” It was determined that other companies are not given this opportunity to structure their panel meetings accordingly. Consequently, Senger suggested deleting the statement because it would “document special treatment for ReGen.”

William McConagha, associate commissioner for integrity and accountability, agreed with Senger's findings and said that he would “excise the language.” He was also coordinator of ReGen's appeal on the earlier 510(k) denial. The letter was copied to Representatives Frank Pallone (D–NJ) and Steve Rothman (D–NJ) as well as Senators Robert Menendez (D–NJ) and Frank Lautenberg (D–NJ).

|

Three federal appellate judges from the Tenth Circuit heard oral arguments on March 9 in TMJI's appeal of $340,000 in civil money penalties for not filing medical device reports for 17 events. They seemed skeptical of HHS and FDA processes that led to the case. All Republican appointees in the Denver-seated courthouse, they asked nearly three times as many questions of the Department of Justice attorney, Peter Maier, as they did of the company's attorney, Lynn Watwood.

Judge Deanell Tacha asked whether TMJI had been lulled into complacency by the letter it received from Schultz, which stated that its protests were being treated as an appeal and being handled by the commissioner's office. Maier retorted: “To their peril!”

Watwood responded that the earlier warning letter TMJI had received demanding the MDRs came from “a lower branch, i.e., CDRH. It was only an opinion from that lower branch and not final disposition of that dispute.” FDA has repeatedly argued in previous cases that appeals can only be disposed of by the commissioner.

For more details on the oral arguments, visit www.transformingfda.com.

|

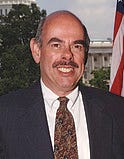

Henry Waxman believes that patients should be free to sue device makers for faulty devices approved through the PMA process. |

Several congressmen have introduced legislation to reverse a court decision that granted federal preemption protection in state product liability lawsuits to medical device makers. The Medical Device Safety Act of 2009 would reverse the 2008 decision in Riegel v. Medtronic that protects medical device companies from lawsuits brought by patients who are injured by devices approved via the PMA process. The bill is sponsored by Representatives Henry Waxman (D–CA) and Frank Pallone (D–NJ). A similar bill is being introduced in the Senate.

“[The Riegel] decision ignores both congressional intent and 30 years of experience in which federal regulation, through FDA, and tort liability played complementary roles in protecting consumers from device risks,” Waxman and Pallone said in a news release.

AdvaMed said it is worried about the bill's effect on product innovation and FDA's ability to protect public health. “This bill does not in any way improve patient safety,” said AdvaMed president Stephen Ubl. “It will, however, restrict patient access to essential medical technologies, produce a chilling effect on medical innovation, create more lawsuits, and ultimately result in higher healthcare costs for all Americans.”

“America needs a central expert authority to regulate medical devices based on a scientific risk-based approach to public health and safety for all Americans, not ad hoc regulation through state court verdicts,” he continued. “Congress provided FDA with this central authority more than 30 years ago, and we should not weaken the agency's effectiveness or ability to meet its mandate to protect the public health and safety.”

Medical device associations and firms recently showed that they differ in their implementation methods and degree of support for a mandated unique device identification (UDI) system.

The Health Industry Distributors Association said in comments to the agency that it supports such a program. But the group argued against making all devices subject to a UDI system, suggesting that there is a wide range of benign disposable medical supplies that do not require the same tracking and security safeguards as high-risk devices. The February 27 comment letter charged FDA with clarifying what constitutes a “medical device,” how the list of products to be tagged with UDI will be developed and by whom, the type of UDI that will be required, and what information about the device should be included.

AdvaMed's comments indicated that it “is a strong supporter of the development and implementation of a UDI system to enhance adverse-event reporting, recall completion, and improvements to medical device safety chain logistics.” But it agreed that waivers should be granted for device types that cannot be identified by or will derive no patient safety benefit from UDI.

GE Healthcare cited comments made by Department of Defense (DoD) and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) officials at a February 12 UDI workshop. First, the company noted that CMS may begin to ask providers for the UDI for reimbursement. “If CMS requires UDI data before FDA has issued its final rule, there is a risk of confusion and lack of consistency,” the company wrote. “GE Healthcare recommends that FDA partner with CMS to develop a common implementation timeline.”

The company also urged FDA to partner with DoD to ensure that the two group's systems are compatible.

Copyright ©2009 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like