June 11, 2006

Originally Published MPMN June 2006

INDUSTRY NEWS

Sticky Bacterium May Have Medical Applications

|

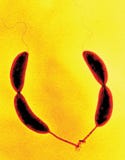

Caulobacter crescentus, a bacterium found in rivers, streams, and tap water, produces sugars that may have applications as medical adhesives. |

A bacterium that uses polysaccharides to stick to surfaces may have medical applications. Research on the Caulobacter crescentus bacterium has been conducted by a team of Indiana University–Bloomington (Bloomington, IN; www.iub.edu) and Brown University (Providence, RI; www.brown.edu) scientists. Their findings are presented in the April 11 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

C. crescentus lives in rivers, streams, and tap water. The bacterium affixes itself to rocks and the insides of water pipes via a long, slender stalk. At the end of the stalk is a holdfast dotted with chains of sugar molecules known as polysaccharides. These sugars are the source of C. crescentus’s strength, according to the researchers.

The scientists allowed C. crescentus to attach itself to the side of a thin, flexible glass pipette. A micromanipulator was used to trap the cell portion of the bacterium and pull it away from the pipette. Approximately 1 µN of applied force was needed to remove a single bacterium from a glass pipette. In 14 trials, the scientists found they had to apply a force of 0.11 to 2.26 µN per cell before the bacterium detached.

Because C. crescentus is so small, the pulling force of 1 µN generates a stress of 70 N/mm2. The stress is equivalent to 5 tn/sq in. By contrast, commercial “superglue” breaks when a shear force of 18 to 28 N/mm2 is applied.

C. crescentus’s glue could be mass-produced and used to coat surfaces for medical and engineering purposes. “Since this adhesive works on wet surfaces, it could possibly be used as a biodegradable surgical adhesive,” said IU–Bloomington bacteriologist Yves Brun.

The polysaccharides are extremely sticky. “The challenge will be to produce large quantities of this glue without it sticking to everything that is used to produce it,” Brun said. “Using special mutants, we can isolate the glue on glass surfaces.”

C. crescentus can live in extremely nutrient-poor conditions, which explains its presence in tap water. Because it exists in tap water at low concentrations and produces no human toxins, the bacterium poses no threat to human health.

The research was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (National Institutes of Health).

Copyright ©2006 Medical Product Manufacturing News

You May Also Like