Welcome to an all-too-familiar customer service experience. You call into a customer service department because your new gizmo isn’t working. Ring. Ring. A machine voice answers and leads you through a generic menu that doesn’t address your problem.

“Representative,” you say into the phone. The machine voice, indifferent to your request, leads you through the same menu. “Representative!” you say again as you push a random number in your handset hoping to reach someone. A new, less-relevant menu is dictated to you by the annoying robot on the other end. After enough pleas for a representative and punching the “0” and the “#” keys, you finally reach someone. And you know how it goes from there…transfers, wait times, and often, no resolution to your problem.

As consumers, we recognize and appreciate good service. And, more pointedly, we loathe bad service. Consumers have proven that they will pay a premium for products with little differentiation if they are presented as part of a quality experience (see Virgin Atlantic, Starbuck’s Coffee, and Nordstrom). These companies have capitalized on creating a compelling experience out of the act of consuming, and they have been rewarded handsomely for it.

Medical device and diagnostic companies have been slow to get into the service game. This is due in part to the fact that their primary customers are intermediary decision makers (physicians, clinicians, hospitals, and nonclinical administrators), not the patients, so ensuring that the experience is good is less critical. For these customers, product quality and trouble-free services are far more important decision criteria. Much has been written about product quality for medical devices, but service quality has been relatively overlooked. With product commoditization becoming more relevant, companies should be targeting service quality as a differentiator to keep customers from defecting to lower-cost producers.

So how would a medical device or diagnostic company develop a trouble-free, reassuring customer experience from initial sales to customer service? The service side of the business is learning what marketing and R&D departments learned back in the 1990s—quality won’t improve unless you understand it from the customer’s perspective. Voice of the customer (VoC) methods can be effective tools for adopting a quality consumer service program.

VoC techniques include interviews, surveys, focus groups, and ethnography. These have proven highly effective in identifying unmet customer needs and developing sound requirements for product development teams.1,2 Consequently, leading medical device companies allocate substantial portions of their annual marketing and R&D budgets for this purpose. Despite their extensive use in product development, VoC techniques are seldom used to design differentiated technical and customer services. This is especially surprising given that close to 80% of the U.S. economy is services-based, and even for product-based companies, services are the fastest (or oftentimes, the only) growing part of the business.3,4

Designing differentiated services requires a structured approach consisting of—at a minimum—the following steps:

? Identify target customers.

? Map out the current process and identify failure points.

? Collect VoC data.

? Prioritize needs.

? Redesign the processes.

? Mitigate risks at key touch points.

? Manage change.

The process typically requires a cross-functional team consisting of representatives from customer service, marketing, operations, sales, quality, information technology, and engineering. A cross-functional team is needed because delivering consistent, differentiated customer service experience requires coordinated efforts of all customer-facing personnel.

|

Table I. An example of a sampling interview plan. |

Identify Target Customers

Although it may seem obvious, confirming and defining customers is a critical step. Often, service personnel are unsure of who their current customers are, let alone who the target customers are. And because most medical device firms are increasing their use of distribution channels and strategic partners, this is a far more common problem than it would appear.

|

Figure 1. The number of customers to be sampled depends on accuracy and cost requirements. Click here to expand. |

A one-page tool called a SIPOC (Suppliers Inputs Processes Outputs Customers) can help address this issue by identifying the customers and clarifying what is delivered to them. In this framework, the customer is defined as a person or organization that receives an output (product or service) from the company. This framework also helps define what value is actually received by the customer. It is interesting to note that for products, the receiver of the device is without exception the customer and the supplier is the company. For services, the customer in the usual sense is both the supplier and the customer. Recognizing this subtle, yet important distinction is key in designing customer-centric services. It enables the organization to actively seek customer feedback at all touch points, not just during complaint handling or annual customer satisfaction reporting.

After initial customer segments have been identified, a sampling plan is drawn up. This is used to collect feedback from a statistically satisfactory number of customers to confirm the initial segments. Table I shows an example of a sampling interview plan.

Determining the number of customers to contact in each segment is more an art than a science. The data collection method (e.g., interview versus focus group) and the difficulty of obtaining the data affect the practicality of the data collection. The practitioner must balance the need for data with the cost of collecting them. Pragmatism should guide such decisions. As a first approximation, the authors use research by Griffin and Hauser on the number of customers to contact (see Figure 1).5 For example, if the goal is to identify 80% of the needs of a customer segment, the research suggests either interviewing approximately seven customers from that segment or conducting four focus groups.

|

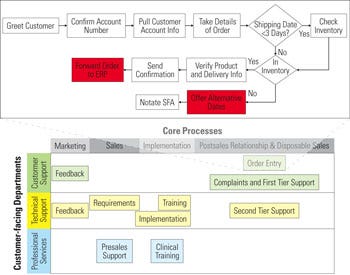

Figure 2. Order-entry process for disposables for existing customers at a large diagnostic equipment manufacturer. The red process boxes indicate those areas in which service quality was considered suspect. Click here to expand |

For each segment, the approach and the information wanted may vary. For example, the types of questions for users would differ from those for procurement personnel at hospitals. An often-overlooked trove of information is from customers who have defected. Most customers defect without saying why. Companies frequently make an error of omission by interviewing only current customers and target customers while ignoring former customers. Seek them out. More valuable information can be gained by learning why customers leave than why customers stay.

Map Out the Current Process and Identify Failure Points

Understanding the current state of the service delivery process is imperative if improvements are expected. Create a detailed process map and identify specific areas in which known failures occurred. Figure 2 shows an example of a service process at a company that designs and distributes sophisticated diagnostic equipment, software, and disposables to large hospitals. The red boxes indicate areas in which service quality was suspected of failing. In the authors’ experience, most of the service-related failures occur at interfaces between personnel, between systems, and between the system and personnel.

For example, a medium-sized medical device company whose product quality was considered best in the industry boasted on-time order fulfillment rates near 95%, which at face value seemed like an acceptable statistic. Deeper digging, however, reveals otherwise. Because of the limited shelf life of the product, delivery dates were tightly synchronized with surgery dates. A late delivery often equated to a delayed surgery. Canceling surgeries due to logistics was unacceptable to the physicians and many of them defected to competitors’ products despite inferior quality. That is, the statistic meant that 5% of all product sales were unacceptable to the customer. It was unacceptable to management as well.

Examination of the issue revealed that the enterprise resource planning system and the sales force automation system were not synchronized in real time. They were synchronized a number of times per day, but not in real time. Consequently, the sales staff did not always have the correct information of buffer inventory, resulting in sales that were greater than what the organization could deliver. Or, the sales team turned away orders thinking that the company would not be able to meet the delivery date when it had plenty of buffer inventory.

|

Figure 3. Choosing the appropriate VoC technique requires assessing its potential against requisite effort. |

Collect VoC Data

Make the most of face time with customers. To develop incisive questions that will lead to valuable information, the OEM must do its homework. Study complaint reports, corrective and preventive action reports, customer satisfaction reports, process maps, and other internal documents. If studies are limited, scan the company’s data repository. Most medical device companies are sitting on large amounts of transaction records and customer data. Take advantage of them by running correlation and trending analysis. Through such research, OEMs can develop a good sense of the extent of the issues and what additional data need to be collected.

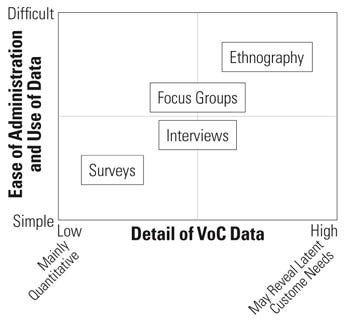

VoC data can be collected through various means. The most common are surveys, interviews, focus groups, and ethnographic studies. The costs and benefits of each can be explained in terms of the ease of application and the quality of the information gleaned. A simplified graph in Figure 3 (p. 74) depicts how the techniques compare.

Most VoC practioners have experience with all of these techniques with the possible exception of ethnography. Ethnographic studies involve carefully observing customers as they interact with a device or service in native environments. Ethnography, developed first by anthropologists, can be a powerful tool, revealing needs that customers neglect to mention in interviews or are entirely unaware of.6 The downside, of course, is that it is time consuming and expensive.

One valuable point on interviewing that the authors have picked up over the years: when conducting interviews, take verbatim notes of the customers’ emotion-laden descriptions. Some of the greatest successes come from interviewing customers in pairs, with one person acting as interviewer and the other as note taker. Specific words that customers choose contain deeper feelings and emotions that explain their perception of quality and ultimately dictate purchase decisions. For example, when customers use emotional phrases such as, “I get angry when I get an answering machine,” let the customer elaborate further and, at times, digress. Emotional engagement from the customer often results in real insights.

It is best to not rely on just one VoC method. Using more than one method ensures that limitations of the techniques are minimized. For example, when using surveys, which are the most economical way to collect a large amount of information, it is valuable to complement them with some interviews.

The collection of VoC data is never finished. Changing customer needs and dynamics in the market mean that new opportunities are always presenting themselves. However, for efforts at service improvement, there is a point of saturation in qualitative VoC data. Once interviews or focus groups are no longer revealing new information, OEMs have the information they need to move on to the next step. For quantitative data collected through surveys, sample size calculations can indicate the degree of confidence in the results.

Prioritize Needs

Because companies cannot meet all customer needs, prioritizing is required. To do so, customer comments are translated into need statements. For example, consider the comment “I deal with your customer service only when there are problems. So, it may not be fair, but I expect you to be available and to give me timely answers.” Such a remark could be translated into the customer need for availability during business hours and response within the same business day.

Once statements have been translated into needs, an affinity exercise is conducted to group together similar needs and remove redundancies. Performance targets and tolerances are then assigned to each major category of needs. Their values depend on the competitive landscape and the cost to satisfy the need.

Companies often use semiquantitative scoring tools (e.g., the Pugh matrix, prioritization charts, or Kano diagrams) to distinguish true differentiators from marginal ones. The author’s clients often prefer the Pugh matrix or some modified version of it due to ease of use.

Redesign the Process and Tools

After the requirements have been agreed on and prioritized, the process must be improved to address the requirements. A series of seminars or visits to nonmedical companies may help an OEM view its current process with a fresh perspective. The authors have discovered that visits to companies in the hospitality industry, financial services, and logistics are especially beneficial to cross-functional teams assigned to change the process.

A series of facilitated brainstorming sessions is an effective tool. Using information about the current process, new requirements from customers, and experiences with how other companies address these requirements, the team is challenged to be innovative. A number of brainstorming techniques are suitable for this, including the idea box, musical chairs, and SCAMPER (Substitute, Change, Adopt, Modify, Put, Eliminate, and Rearrange). One useful tool is the mind map.

The mind map begins with a focused statement written in the middle of a large writing wall. The goal of a process element, say “Maintain on-time delivery above 99.99%,” is the touch-off point for discussion. As ideas come up, they are written immediately adjacent to the center purpose statement. As ideas trigger other ideas, a line is drawn that connects related thoughts. In contrast to the normal brainstorming process of listing ideas, the connectedness provides a history of the thought process and proves fertile ground for idea incubation. This process is effective because it enables a team to think in parallel, not serial, a vital prerequisite for innovation.

After the ideas are collected, they are rationalized by the team. Does the idea make sense? Would it meet customer needs and enhance the service experience? Fleshing out the idea and developing high-level details can begin to breathe life into it. The ideas should be ranked to determine which ones the team will move forward with. A scoring mechanism is useful for this purpose. Each person is given a limited number of points and is allowed to vote, adding weight to the ideas and determining relative rank. The person may allocate all points to one idea or spread them across many. This can be done directly on the mind map or on a separate scoring matrix. Winning ideas are then assigned to a team member for development and refinement.

A follow-up meeting is held after team members have developed solutions. The centerpiece of the meeting is the development of the future state of the service process and the incorporation of the service solutions. The team should refer back to the current-state process map for this exercise (Step 2). While developing the new process, the team should keep in mind how the customer will experience the process. One effective tactic to ensure the customer perspective is represented is to assign a team member to think like a customer during process design. That team member’s job is to cognitively simulate how the process would affect the end-user experience.

|

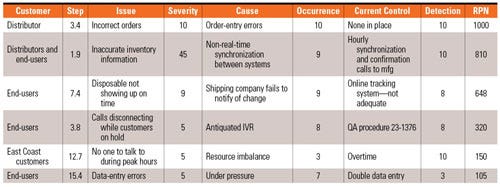

Table II. Risk priority number (RPN) ratings are used to identify service risks and mitigate them. The items highlighted in red are above the threshold limit for the process design team. They need to be addressed and reduced to an acceptable level. |

Mitigate Risks at Key Touch Points

Once the new process is designed, identify all points at which customers interact with the company, similar to the exercise conducted in Step 2. These are the make or break points at which customer experience is ultimately determined. Using a risk management tool, the risk priority number (RPN), the team identifies the potential failures that can occur, what the likelihood of failure is, and the severity associated with it. All customer touch points with an RPN score above a certain threshold are subjected to a risk mitigation exercise (see Table II).

In this exercise, process elements, potential issues, and root causes are identified. Their severity, occurrence, and detection are scored on a 1–10 scale. They are multiplied for a combined RPN rating. A score of 1000 represents the highest risk. Process elements with scores above the typical threshold value of 200–300 are reviewed to improve control measures. This is similar to how RPNs are used to identify and mitigate health hazards. With the new process designed and risk mitigation strategies in place, the process is ready for implementation.

Manage Change

As with any major change, the service process needs to be managed. One of the prerequisites for success is executive commitment. It has to be seen as an important goal, which means that top management needs to be involved intimately throughout the process. Secondly, the implementation team needs to be involved in designing the solution. This will not only create a sense of ownership, but facilitate a smooth transition between functions as work is handed off.

Depending on the scale of implementation, conducting a small pilot implementation can be effective to try out the process in a managed environment, solicit feedback, and fine-tune the process before full-scale implementation. During the pilot of one process improvement effort, the authors received more than 150 ideas to improve it from employees involved in the process. We were able to incorporate 60 of the ideas, resulting in a more robust and effective final process.

Conclusion

Increasingly, customer service is becoming a significant or, oftentimes, the only growth opportunity for product companies. Excellent service delivery is hard work and operationally difficult. It requires explicitly defining what customers want, measuring how well the company delivers on customer requirements, and ensuring the company has the right people to provide that exemplary service. VoC techniques, when used in a structured way, enable companies to deliver superior, differentiated customer experiences.

References

1. G Churchill and C Brodie, Voices into Choices (Madison, WI: Joiner Publication, 1997).

2. T Kelley, The Art of Innovation (New York: Currency Books, 2001).

3. US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

4. B Auguste, E Harmon, and V Pandit, “The Right Service Strategies for Product Companies,” McKinsey Quarterly 1 (2006): 41–51.

5. A Griffin and R Hauser, “The Voice of the Customer,” Marketing Science 12, no. 1 (1993): 1–27.

6. S Wilcox, “Ethnographic Research and the Problem of Validity,” Medical Device + Diagnostic Industry 30, no. 2 (2008): 56–61.

Sung Pak is partner at Value Creation Institute. Ben Yoder is business process designer at Knowledge Universe Technologies.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)