As meaningful use is being defined, manufacturers should demonstrate how their technologies improve quality of care.

January 10, 2011

|

Figure 1. Several vendors play a role in meaningful use. Click figure for larger image. |

As the healthcare industry works with President Obama’s administration to further develop the definition of meaningful use, wariness about meeting the 2015 deadline for meaningful use of health information technology (IT) has emerged as a key issue. A survey released by PricewaterhouseCoopers in June found that 80% of hospital chief information officers (CIOs) are concerned with their organization’s “ability to meet meaningful use requirements within the specified time frame.”1 The final regulations for meaningful use issued by HHS on July 13, 2010, provided some increased flexibility in meeting requirements, but the pressure to match still-evolving standards remains a major challenge for providers. For device makers, there is a significant opportunity to help supply technologies that address these challenges.

Why Meaningful Use Matters

For the next few years, meaningful use will be one of the most important topics among healthcare providers. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, signed into law by President Obama as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) in 2009, set aside more than $36 billion in incentive payments for the adoption and meaningful use of certified electronic health records (EHRs). Providers that fail to adopt certified EHRs by 2015 will face penalties in the form of reduced Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements. The key to certified EHRs will be defined by meaningful use of IT based on the final definition.

Why should meaningful use matter to medical device manufacturers? Three important reasons come to mind. First, debate about meaningful use so far has focused on EHRs, but the ongoing discussion represents an opportunity for device makers to help move the industry to a more inclusive final definition. Second, the key benefits that policymakers hope to achieve from meaningful use—higher quality and more cost-effective healthcare— are also benefits of many patient-bedside devices. This change means that providers could be considered meaningful users with technology that is already in place. And third, the current discussions open a door for device innovations that could have a substantial effect on future healthcare quality and safety.

Influencing the Final ?Definition

Meaningful use will be defined in three stages, tied to incentive payments in 2011, 2013, and 2015. The first stage has already been determined. To meet the requirements, hospitals and other providers must be able to

Demonstrate use of certified health IT in a meaningful manner.

Validate that certified IT is connected or interoperable in a manner that provides for electronic exchange of health information to improve the quality of healthcare.

Use certified technology to submit data to the government on specific clinical quality measures and performance metrics.

EHRs have been at the center of discussions about clearing these hurdles, and adopting them represents a vital step for providers. But EHRs are not the whole story. Other health information technologies, including interoperable medical devices, already play a critical role in the transfer of important patient information. That means device makers have just as much insight and just as much of a stake in what constitutes the use of technology in a meaningful manner as any other vendor in the health IT industry (see Figure 1).

As providers prepare to qualify for the first wave of incentives, it is important to note that all of the requirements listed above focus on use and not on simply having health IT in place. Any manufacturer of medical devices can easily talk about numerous ways providers can use device IT in a meaningful manner. However, certification is crucial. Only health IT components that are certified by CMS and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) will qualify as technology that helps providers meet meaningful use requirements. And for at least the next five years, those are the technologies in which providers will focus their investments.

Device manufacturers must not sit idly on the sidelines while others figure this out. Both existing and emerging device technologies can play a key role in improving healthcare, and we must make sure policymakers hear and consider this as they continue to define meaningful use. Hospira, for example, is actively working to interject a device maker’s perspective. Among the steps the company has taken is providing comments to the National Quality Forum, which serves as the source for the quality measures that are included in the meaningful use requirements. Hospira submitted recommendations on serious reportable events (SRE) related to clinical decision support tools and the interoperability of health IT.

Every device maker with a product that could potentially improve the quality, safety, or cost of healthcare should make sure the ultimate definition of meaningful use goes beyond EHRs to include device technology that is used today by providers.

Devices Could Make Providers Meaningful Users Now

The recent PricewaterhouseCoopers survey also found that one-third of CIOs are concerned about vendor readiness. This underscores the fact that hospitals and other providers cannot achieve meaningful use on their own. They are relying on IT vendors to help them take the critical steps that will improve healthcare quality and safety, while meeting the designated timelines. That raises a question—realistically, how quickly can a provider become a meaningful user of health IT?

One of the hurdles providers must clear to meet the 2011 requirements is to “validate that certified health information technology is connected, or interoperable, in a manner that provides for electronic exchange of health information to improve the quality of healthcare.” Purchasing and installing technology for EHRs and training clinicians how to use it effectively can take one to two years. As a result, hospitals that don’t already have systems in place could easily miss the first deadline. There is a way to clear this hurdle much faster.

A key area for improvement in quality of care is eliminating medical errors. By now, the Institute of Medicine’s 2006 statistics on the effect of medication mistakes are well known. Each year, more than 1.5 million people are harmed by medication errors and 400,000 preventable drug-related injuries occur in hospitals; an additional 530,000 drug-related injuries affect just Medicare recipients at outpatient clinics; and about 800,000 occur in long-term care settings. Fully functional EHRs could help address this problem. Certain medical devices that are interoperable with other hospital technologies could be implemented in a fraction of the time it takes to get an EHR system up and running. One example of interoperable medical devices, smart pumps, can be integrated with other systems to provide near real-time autodocumentation to EHRs.

A 2008 time and motion study by Ascension Health and Kaiser Permanente found that nurses spend two and a half hours per each 10-hour shift documenting patient information, which reduces their one-on-one quality time with patients.2 Autodocumentation to EHRs can help improve nurse work flow, effectively giving some of that time back to patient care.

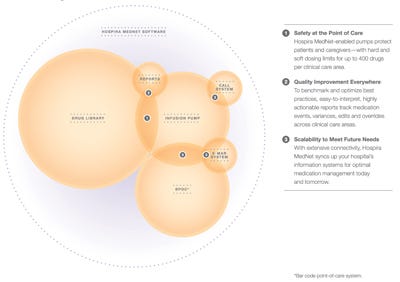

Incorporating infusion devices in closed-loop medication delivery, a process that automates all the steps from the ordering to the administration of medications, can help contribute to the quality of care. This method involves ensuring that interoperable safety software can electronically transfer a patient’s medication administration information through a hospital’s network to a smart infusion pump using bar code medication administration (BCMA; see Figure 2). This connectivity helps medical professionals check the five rights of medication administration—the right patient is receiving the right medication at the right dosage, through the right route, at the right time. The five-rights verification has been shown to generally reduce medication errors by 65%-86%.3

|

Figure 2. Several elements come together to create an effective interoperable software medication management system. Click figure for larger image. |

The closed-loop medication administration process will be included in the 2013 standards for meaningful use and could be one of the easier requirements to meet. Providers can install and implement interoperable medical devices much faster than they can full EHRs, and many hospitals already have them in place. About 60% of U.S. hospitals are currently using smart pumps, and of those that have not adopted them, 62% plan to do so within the next three years. Similarly, 68% of health system facilities are using bar code scanners or readers at the patient's bedside.4 This number compares to fewer than 25% of hospitals that have implemented a fully operational EHR system across the organization, based on figures from the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS).5 Other sources estimate that only 1.5% of U.S. hospitals have completely switched to EHRs.6

Unfortunately, the vast majority of providers are not getting the full benefit of integrated smart pumps and BCMA systems. Only 14% of health system facilities have linked the two technologies in some way, and only a handful have fully integrated them to achieve the benefit of closed-looped medication administration. This lack of integration represents a missed opportunity to reduce medical errors and, more importantly, the number of people harmed by them. While BCMA systems are certified for meaningful use, the smart pump technology that helps deliver the closed-loop benefit is not. Certification of smart pumps, along with the certification of the integrated systems, would accelerate the pace at which providers adopt them, along with the pace at which medication errors are eliminated.

Of course, inclusion of these medical devices would still represent only part of a provider’s journey to achieving meaningful use, even for the data collection stage that is the primary focus of 2011. But it would position providers to receive incentives, which could drive earlier adoption of other health IT. And that could help them achieve the final stage of meaningful use—improved patient outcomes—much sooner.

The Door to Future Innovation

The current focus on meaningful use represents progress for healthcare in the United States. But progress does not stand still. Specific health IT products that are certified for the 2015 deadline inevitably will be surpassed by newer technologies that provide even greater benefits. The ultimate definition of meaningful use must account for this reality.

Many of the device functions mentioned so far are only possible if a medical device is interoperable with other devices or with a healthcare facility’s larger IT network. In fact, one reason some hospitals may not have linked smart infusion pumps to the BCMA systems could be that the systems are not able to talk to each other. That’s because many device makers still use proprietary standards when developing their technologies. While this might seem like a smart move competitively, in the long run it does a disservice to the entire healthcare industry, including device makers.

As hospitals explore what they must do to become meaningful users of health IT, many of them are consulting with doctors, patients, and insurers. Each of these groups has a vested interest in reducing medical mistakes and that factor alone could be enough to drive widespread interoperability. Interoperability will drive innovation and enable manufacturers to introduce new products fast and cost effectively.

How meaningful use is ultimately defined will be another innovation driver. For instance, the third requirement for the 2011 phase of meaningful use is that providers must “use certified technology to submit data to the government on specific clinical quality measures and performance metrics.” This requirement could lead to the development of new reporting tools, as well as new uses for existing devices. For instance, software surveillance devices that monitor data and use alerts to help hospitals identify and isolate infections also could provide an easy means for reporting on meaningful use metrics.

Conclusion

It is an exciting time for healthcare. Quality and safety are common goals for everyone involved, including the clinicians who deliver care and the companies that make products to support clinicians in their work. However, practicality, competitive roadblocks, and traditional approaches can get in the way of advancing efforts to make a meaningful difference in achieving those goals.

The ongoing discussions about meaningful use have great potential to help usher in a new age of quality-focused healthcare. As the initial meaningful use deadline for healthcare providers approaches, device manufacturers should view it as a fresh starting point. Many companies probably have existing products or prototypes that could help drive quality, safety and cost savings as well as improve outcomes for patients. There is every indication that the policymakers responsible for developing and implementing meaningful use want to hear about technologies that contribute to those goals. Device makers have a chance to demonstrate on a broad scale how their technologies can affect the future of healthcare and should seize this opportunity.

References

1. Ready or Not: On the Road to the Meaningful Use of EHRs and Health IT, PricewaterhouseCoopers Health Research Institute, June 2010.

2. Hendrich A et al. “A 36-Hospital Time and Motion Study: How Do Medical-Surgical Nurses Spend Their Time?” The Permanente Journal no. 3 (2008): 29-31.

3. “Medication Errors Occurring Within the Use of Bar-Code Administration Technology,” Pennsylvania Patient Safety Advisory 5, no. 4 (2008): 122–126.

4. “The State of Pharmacy Automation, Pharmacy Purchasing and Products,” Pharmacy Purchasing & Products (2009); available from Internet: www.pppmag.com/pp-p-state-of-pharmacy-automation-2009/the-state-of-pharmacy-automation-summary.

5. Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society, 21st Annual 2010 HIMSS Leadership Survey; available from Internet: www.himss.org/2010survey/docs/21stannualleadershipsurveyfinal.pdf.

6. Ashish K J et al, “Use of Electronic Health Records in U.S. Hospitals,” New England Journal of Medicine 360, no. 16 (April 16, 2009).

Symeria Hudson is vice president of continuous improvement and transformation at Hospira Inc. (Lake Forest, IL).

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)