Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry Magazine MDDI Article Index

January 1, 2006

Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry Magazine Originally Published MDDI January 2006 INNOVATION An innovative and novel technology is not guaranteed market acceptance and adoption. For many technologies, achieving acceptance requires a shift in specialties or practitioners. By Michael Orrico

Innovative product development organizations seek to predict which adoption route new technologies will take. Some familiar products achieve rapid adoption (VCRs, PCs), while other products steadily gain acceptance over decades (washing machines). Using diffusion equations, market models extrapolate future adoption of technologies based on their initial market effect. Although these models help us understand how consumers accept technology, they give us little insight about why technology is adopted. In healthcare, factors beyond performance, cost, and convenience determine adoption. Managed-care organizations (MCOs), institutional policies, and medical societies influence product choices much more than individual physician preference. Accordingly, device developers must understand the drivers behind acceptance of innovations and incorporate that understanding into the design of new products. Given the factors that influence adoption, a new medical treatment has a better chance of being adopted if the technology requires a shift of specialties or practitioners. In fact, the change of practitioner may be more significant than any actual improvement in patient outcome in early commercialization. The reasons for this have to do with the technology's managed-care economics and practitioners' motivation for prestige. A Tale of Two Procedures In his book The Inventor's Dilemma, Clayton Christensen presents a theory of disruptive technology.1 This theory provides the groundwork for the argument that practitioner change is important to a new technology's market acceptance. Disruptive technologies are simpler, more-convenient, lower-cost alternatives to established technologies or practices. However, they do not have to be superior to established technologies or practices. In fact, a disruptive technology may actually be less effective. Christensen contends that, many times, a disruptive technology still beats out an established technology even though it may be only “good enough.” Table I lists some examples of established and disruptive technologies in healthcare. These examples involve an explicit change in practitioners rather than the advent of a revolutionary technology. For example, an ultrasound exam done in a general practitioner's office replaces a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan done by a radiologist at a special hospital MRI suite. Or, an angioplasty procedure done by an interventional cardiologist in a catheterization lab replaces a surgical procedure done by a cardiac surgeon and full staff in a cardiac operating room. Patients suffering from coronary artery disease have seen a drastic change of treatment over the last two decades. These patients have blockages in their cardiac vessels that limit blood flow to heart muscle. If blood flow is constricted enough, the heart muscle deteriorates, leading first to pain (angina), then to a heart attack. Since the 1960s, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has been the gold standard for the long-term treatment of severe coronary artery disease. For this surgical procedure, the patient is placed on bypass. Bypass consists of the patient's heart being stopped and blood routed to a heart-lung machine. While the patient is on bypass, a cardiac surgeon grafts a short blood vessel obtained from the patient's arm or leg onto the heart to shunt blood around the blockage in the coronary artery. The term gold standard is more than a cliché. Physicians use the term to denote the most applicable and most effective long-term treatment possible for patients with diseased coronary arteries. If patients are in otherwise fair health and can withstand CABG surgery, they will very likely have excellent results with no complications. Thus, CABG has become the standard against which all other treatment options are measured.

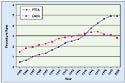

Cutler and Huckman compared the adoption of PTCA and CABG procedures in New York State, which is typical of the rest of the United States (see Figure 1).2 Through the 1980s, PTCA and CABG both grew for several reasons. First, the aging demographic and the poor diet of the U.S. population increased the incidence of coronary artery disease. Second, the risks associated with both procedures declined. This decline enabled surgeons and interventional cardiologists to treat less-severely diseased patients with interventional techniques rather than medication. Finally, healthcare cost pressures were brought on by managed care. In response, medical centers began to market general cardiac care, since cardiac procedures produced good revenue and profits. That way, hospitals could offset losses on many other procedures. Initially, PTCA was effectual only on noncritical blockages. But cardiologists continued to learn, and concurrent advances in PTCA technology were made—most notably, the development of stents. Cardiologists found they could go after patients who previously would have been referred for CABG surgery. For many years during this shift, cardiac surgeons did not realize that their scope of practice was eroding, because they saw a growing number of cardiac patients. So, most cardiac surgeons hung on to their established techniques and were not motivated to learn new skills. Meanwhile, interventional cardiologists and device firms championed PTCA to the MCOs. They funded research trials and lobbied for reimbursement mechanisms from government and private insurers. MCOs were easily convinced to cover PTCA procedures because they were typically 30% lower in cost than CABG procedures. By the mid-1990s, the advent of stents enabled PTCA to eclipse CABG. Stents are tiny mesh tubes that are left in coronary arteries after PTCA to keep blockages from recurring. Stents significantly reduced post-PTCA complications of restenosis (recurrence of blockage). Interestingly, until stents augmented PTCA, complication rates for that procedure were many times greater than for CABG. Even with stents, the restenosis complication rate remains higher for PTCA than for CABG. Yet many PTCA proponents argued, and continue to argue, that the PTCA procedure is safer than CABG. They say that because the patient is not anesthetized, the heart is not stopped, and the incisions are much smaller, the procedure carries less risk. In response to the shift of patients from CABG to PTCA, some innovative cardiac surgeons and medical device firms pioneered off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (OPCAB) procedures in the mid-1990s. OPCAB is often considered a kinder, gentler CABG. In this procedure, the surgeon still grafts a blood vessel onto the heart to bypass a blockage. New stabilizing instruments and videoscopic equipment enable the surgeon to perform the procedure through a small incision between the ribs while the heart is beating. Therefore, OPCAB has the potential to be a gold-standard procedure that avoids the apprehension that comes with a large incision and stopped heart. Currently, OPCAB procedures require general anesthesia; however, new techniques in conscious sedation may overcome even this objection.

As Table II shows, PTCA and OPCAB have comparable advantages and disadvantages. Yet, OPCAB surgery remains a small niche within total CABG procedures, at about 20% adoption, even though OPCAB has been around for more than 10 years. In the PTCA-CABG example, the practitioner-change argument explains the difference in adoption. Initially, PTCA adoption grew when cardiologists focused on patients whose conditions did not threaten the established practices of cardiac surgeons. As innovation and learning progressed, cardiologists went further into the surgeons' market and treated CABG-candidate patients with PTCA. Cardiologists saw PTCA as a way to grow their customer base by applying their skills to a larger patient population. In addition, cardiologists chose which patients to refer to surgeons, which added to the rapid adoption. In essence, PTCA-proficient cardiologists decided which patients they would treat. Thus, cardiologists integrated forward, meaning they increased the scope of their practice from only diagnosing coronary artery disease to treating it. Why Practitioner Change Facilitates Adoption Is the PTCA-CABG example a special case, or can we generalize the conclusion that a practitioner change will facilitate the adoption of new healthcare technologies? Like any high-risk, established business, the healthcare system inherently resists change—especially technology-driven change. Over the past two decades, the medical community has come to view technology as raising costs with no clear measures of improved outcomes in return. Hall and Khan state the underlying issues in adoption of technology in the New Economy Handbook: Adoption of a new technology is often very costly for various reasons . . .; employees need to be trained to operate the new technology [and] there will be a cost from lost output. In a world where demand is uncertain, [hospitals and practitioners] are likely to be unsure about whether or not they can recoup the cost of adopting the new technology, or how long it may take to recover the cost. As a result, it might not be worthwhile for them to adopt even if the technology has the potential of improving productivity or product [outcome] quality.3 The key to adoption is finding an advocate to pull the new technology through, and that advocate needs motivation. Motivated practitioners are critical to rapid adoption of healthcare technology for two central reasons. First, and most important, the new, highly motivated practitioners will champion a new technology against opposition from the MCOs. Second, these practitioners create and become proficient in the new specialties or subspecialties that focus on the new technology. Championing Technology through MCOs If we consider government programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and state programs to be MCOs, then MCOs pay for the majority of medical care in the United States. MCOs' central purpose is to control the level of medical expenditures while providing an acceptable level of care. Therefore, MCOs have no incentive to invest in or encourage healthcare technologies that do not reduce costs, regardless of potential outcome improvement. Folland et al. have reached the same conclusion: Managed care arrived with the hopes that it would control healthcare expenditure increases by removing the financial incentives for physicians to over-prescribe, over-treat and over-hospitalize patients. The same flattening of incentives—no extra money for extra treatment—potentially dampens the physician's interest in cost-increasing technologies . . . and slows innovation.4 A study of medical technology manufacturers and MCO managers conducted by the RAND Corporation on new medical technology echoes this sentiment: Some of the manufacturers told us that the advantages of their technologies over alternative therapeutic approaches included important improvements in quality of life for patients. Among these manufacturers, there appears to be general agreement that such benefits to patients are not given much weight in adoption decisions by MCOs.5 Healthcare in the United States thus involves an additional factor that causes established practitioners to refrain from adopting new technologies. In fact, the MCO system of reimbursement charge coding institutionalizes the sluggishness of incumbents in adopting innovations. As the RAND study explains: When existing [reimbursement] codes are not appropriate, the manufacturer faces the costly and time-consuming task of obtaining new codes. This task generally requires showing that physicians are using the new procedure, which, in turn, requires diffusion of the technology despite the lack of appropriate CPT [reimbursement] codes and, often, support from medical-specialty societies.5 Thus, a paradox arises: a new technology needs to have a substantial base before attaining even modest adoption in the mainstream. This situation requires that motivated practitioners become champions of an innovation's safety, effectiveness, and use in order to establish ample reimbursement for the technology from MCOs. A new practitioner in the relevant medical specialty is most likely to be that champion. Creating New Specialties Proliferation of specialties has been a force in medicine for more than a century. An observation made by William Mayo in 1910 seems relevant today: “The sum total of medical knowledge is now so great and widespreading that it would be futile for any one . . . to assume that he has even a working knowledge of any part of the whole.”6 Therefore, an expanding variety of specialist practitioners, with various skills and knowledge, are competing for a relatively static number of diseases. Practitioners want to apply their portfolio of skills to the biggest segment of patients. Practitioners also relish the prestige of inventing new medical specialties, even if they are only slightly different from existing specialties or are combinations of existing specialties. Conclusion The PTCA-CABG experience and general evidence show that new practitioners are the key to rapid adoption of medical innovations. This conclusion has strategic implications for both healthcare technology innovators and established medical device firms. First and most obvious, medical technology firms should design products that can be used by another (preferably lower-priced) level of practitioner. For example, the firm should add or remove features so that the product can be used by a physician's assistant or registered nurse rather than only by a physician. Device manufacturers that supply established practitioners need to provide extra motivation for these customers to adopt new technology. Instead of ignoring competitive innovations, manufacturers should alert their established customers that change is on the horizon. Then, the threat of a disruptive technology provides incentive for both established firms and practitioners to improve existing technologies—especially in terms of cost—and make it harder for disrupters to enter the market. In addition, established firms should collaborate with established practitioners to create new subspecialties built around innovation. Finally, established firms should be slow to discount competitive technologies that appear inferior to the standard of care. As with PTCA, the economics of managed care and the diligence of new practitioners may combine to make the technology “good enough.” References 1. Clayton Christensen, The Innovator's Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fall (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1997), 28. 2. David M Cutler and Robert S Huckman, “Technological Development and Medical Productivity: The Diffusion of Angioplasty in New York State,” Journal of Health Economics 22, no. 2 (2003): 187–217. 3. Bronwyn Hall and Beethika Kahn, “Adoption of New Technology,” in New Economy Handbook, ed. Derek C Jones (San Diego: Academic Press, 2003), 5–20. 4. Sherman Folland, Allen C Goodman, and Miron Stano, The Economics of Health and Health Care (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001), 320. 5. Steven Garber et al., Managed Care and the Adoption of Emerging Medical Technologies (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2000), 22–23. 6. Stanley Joel Reiser, Medicine and the Reign of Technology (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1978), 150. Michael Orrico is a member of the Healthcare Council of the Gerson Lehrman Group (New York City). He can be contacted at [email protected]. Copyright ©2006 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry |

You May Also Like