Zecchini Clinical laboratory tests account for more than $30 billion in annual expenditures in the United States, according to the Center for Medicare Advocacy.1 More than 6 billion tests are conducted yearly in more than 200,000 testing sites.2

In response to some public health concerns over the largely unregulated laboratory services industry, Congress passed the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) in 1988 to establish standards for laboratory testing and ensure the accuracy and reliability of patient test results regardless of where the test was performed. Under this law, a laboratory is defined as any facility that performs laboratory testing on specimens derived from humans for the purpose of providing information for the diagnosis, prevention, or treatment of disease, or impairment of, or assessment of, health.3

FDA has asserted its jurisdiction over laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) by way of guidance documents concerning in vitro diagnostic multivariate index assays (IVDMIAs), a subset of LDTs. This move has sparked much discussion and debate among stakeholders because it represents a major shift in the agency’s approach to LDTs. This article examines FDA’s legal authority to regulate IVDMIAs and its decision to implement this new policy through the use of guidance documents rather than through the public rulemaking process.

Draft Guidance: IVDMIAs

Until recently, LDTs had not been subject to FDA 510(k) premarket notification or premarket approval (PMA) requirements. FDA’s regulatory focus was on genetic tests sold as kits and the analyte-specific reagents (ASRs) used to make genetic LDTs. FDA has generally exercised enforcement discretion over LDTs and has not actively regulated them.

On September 7, 2006, FDA released Draft Guidance for Industry, Clinical Laboratories, and FDA Staff: In Vitro Diagnostic Multivariate Index Assays with a 90-day public comment period.4 Reasoning that “clinical laboratories that develop [in-house] tests are acting as manufacturers of medical devices and are subject to FDA jurisdiction under the act,” the draft guidance sets out the regulatory rules for companies and laboratories that manufacture IVDMIAs.

On July 26, 2007, FDA issued a second version of the IVDMIA guidance document with an additional 30-day comment period. In the revised version, FDA narrowed the scope of and more clearly defined IVDMIA products that would be subject to the approach defined in the guidance. An IVDMIA is a device that:

? Combines the values of multiple variables using an interpretation function to yield a single, patient-specific result (e.g., a classification, score, index, etc.), that is intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions, or in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease.

? Provides a result whose derivation is nontransparent and cannot be independently derived or verified by the end-

user.

The draft guidance gives examples of tests that are and are not IVDMIAs to further clarify its definition. Examples of existing IVDMIAs that lack premarket clearance or approval to date include gene expression profiling assays for breast cancer prognosis; products that predict disease risk by integrating results from multiple immunoassays; and those that predict risk or diagnose disease by integrating age, sex, and genotype of multiple genes. The revised guidance also provides multiple examples of devices that are not considered IVDMIAs.

FDA will classify an IVDMIA based on its intended use and on the level of control necessary to ensure the safety and effectiveness of the device. Commercially marketed IVD test systems will be assigned to one of three categories based on their potential risk to public health. These categories are waived tests, tests of moderate complexity, and tests of high complexity. Each specific laboratory test system, assay, and examination is graded for level of complexity by assigning scores to each of seven criteria. These categorization criteria are knowledge, training and experience; reagents and materials preparation; characteristics of operational steps; calibration and quality control; proficiency testing materials; test system troubleshooting and equipment maintenance; and interpretation and judgment. CLIA categorization will be announced in a Federal Register notice that will provide opportunity for comment on the decision. On May 7, 2008, FDA released the Draft Guidance on Administrative Procedures for CLIA Categorization. Notice was published in the Federal Register to provide the opportunity for comment, but no comments were received. FDA continues to address IVDMIAs and LDTs where risks are perceived, even while draft IVDMIA guidance is pending. FDA believes most IVDMIAs fall under the moderate-risk (Class II) or high-risk (Class III) device categories.4

Federal Rulemaking versus Guidance Documents

It is easy to understand the practical pressures on FDA given the agency’s limited resources. But many legal observers question FDA’s compliance with the Administrative Procedures Act (APA), which governs when and how agencies must go through the formal rulemaking process (see the sidebar, “The Rulemaking Process”).

In September 2006, the Washington Legal Foundation filed a petition with the agency saying that FDA “lacked the statutory authority to regulate tests developed by laboratories for their own use and offered only to healthcare professionals.” The foundation further said that “clinical labs have long been subject to regulation by another federal agency—CMS and its predecessors—pursuant to [CLIA].” Codifying FDA’s proposal “could undermine effective healthcare by crippling these labs’ ability to quickly develop tests…” the foundation said.5

The American Clinical Laboratory Association (ACLA) recommended that FDA issue a proposed rule to address this topic through the formal notice-and-comment rulemaking process rather than through subregulatory guidance, according to ACLA president Alan Mertz. He said that FDA should work with CMS to enhance CLIA regulations. Such an approach could address the concerns that prompted FDA to issue the draft guidance in the context of the regulatory framework specifically designed for clinical laboratories and the services they provide. He said that systematic and rigorous enforcement of these requirements by CMS could approximate the independent validation of clinical relevance that FDA seeks to achieve for IVDMIAs through its draft guidance.

Others have said that even if FDA has the statutory authority to regulate IVDMIAs, the agency would be misguided to do so. In its proposal, FDA said that it is troubled about how IVDMIAs rely on algorithms to calculate specific results, and then report those results in a way that would make it difficult for doctors to understand them without prior knowledge of the test. And confounding this situation is the observation that FDA has recently taken a piecemeal approach toward regulating IVDMIAs by sending letters to some test developers, including Genomic Health, Correlogic, LabCorp, Agendia, and InterGenetics, suggesting that CLIA certification may not be enough to bring their products to market.

Today, although FDA continues to rely on its substantive rulemaking authority, the efficiency of rulemaking as a regulatory tool has been reduced. The internal process of issuing regulations is far more cumbersome. Although the essential elements of informal notice and comment remain the same, there are now layers of review in the Office of the Commissioner, the Office of the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, and the Office of Management and Budget. Moreover, concerns about economic burdens and paperwork reduction must now be taken into account in every major new regulatory proposal. For these reasons, FDA has, with increasing frequency, resorted to issuing less-formal guidance documents to manufacturers on matters of mutual interest and concern.

Although guidance documents cannot legally bind FDA or the public, the agency recognizes the value of guidance documents in providing consistency and predictability. In 1997, Congress specifically addressed the practice of using guidance documents by adding section 702(h) to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (Good Guidance Practices), which now generally governs their use. The purposes of guidance documents are to provide assistance to the regulated industry by clarifying requirements that have been imposed by Congress or issued in regulations by FDA and by explaining how industry may comply with those requirements and provide specific review and enforcement approaches to help ensure that FDA’s employees implement the agency’s mandate in an effective, fair, and consistent manner. An important element of the Good Guidance Practices section is its inclusion of the public in the formulation of guidance documents.

For example, a petition for rulemaking was filed on September 26, 2006 by Kathy Hudson, PhD, director of the Genetics and Public Policy Center for Johns Hopkins University; Peter Lurie, MD, deputy director of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group; and Sharon Terry, president and CEO of Genetic Alliance. It requested that CMS create a genetics specialty and establish standards for proficiency testing. CMS stated that it is required to conduct a number of analyses in determining whether the public rulemaking process should be implemented.

In its analyses, CMS referred to Executive Order (EO) 12866, which limits agency rulemaking to instances in which regulations “are required by law, are necessary to interpret the law, or are made necessary by compelling public need.” Furthermore, in deciding “whether and how to regulate,” EO 12866 requires agencies to assess all “costs and benefits of available regulatory alternatives, including the alternative of not regulating.” The agency is obligated to select from available alternatives “that maximize new benefits.” In the end, “the agency must adopt a regulation only upon a reasoned determination that the benefits of the intended regulation justify its costs,” and then tailor its regulations to impose the least burden on society…consistent with obtaining the regulatory objectives…”6

FDA states in its guidance that it has applied the “least burdensome approach.” Section 205 of the FDA Modernization Act of 1997 is premised on the principle that regulatory requirements should not exceed what is required to protect and promote the public health. This provision requires FDA, in consultation with the product sponsor, to consider the least burdensome means to enable appropriate premarket development and review of a device without unnecessary delays and expense to manufacturers.

FDA’s Assertion of Authority

The revised guidance document clearly articulates two reasons for FDA’s assertion that IVDMIAs pose more risks than other LDTs. First, IVDMIAs “are developed based on observed correlations between multivariate data and clinical outcome, such that the clinical validity of the claims is not transparent to patients, laboratorians, and clinicians who order the tests.” Second, some IVDMIAs have “high-risk intended uses” and patients rely on them to “make critical healthcare decisions.” These factors, taken together, led to the conclusion that “there is a need for FDA to regulate these devices to ensure that the IVDMIA is safe and effective for its intended use.”4

FDA has recognized the skill and expertise of CLIA-regulated, high-complexity laboratories to use reagents in test procedures and analyses of their own development, and the agency generally has not regulated laboratory-developed testing services. This determination has been based in part on the need to manage the agency’s limited review resources. Nonetheless, because IVDMIAs incorporate articles of software “intended for use in the diagnosis of disease,” they are considered devices under 21 USC 321(h)(2). Relevant parts include the following:

? Section 513(f)(1) of the act, 21 USC 360c(f)(1), which states that “[a]ny device intended for human use which was not introduced or delivered for introduction into interstate commerce for commercial distribution before the date of enactment of this section is classified into Class III” unless it has been found substantially equivalent to a Class I or Class II device, or unless it has been reclassified into Class I or Class II.

? Under section 515 of the act, 21 USC 360e (f)(1), a device that is classified into Class III by operation of section 513(f)(1) “is required to have, unless exempt under section 520(g), an approval under this section of an application for premarket approval.”

? Software is a device for which premarket approval is required to establish safety and effectiveness. The appropriate vehicle for such approval is the submission and FDA review of a premarket approval application (PMA). PMA requirements are set forth in FDA’s regulations (21 CFR part 814).

|

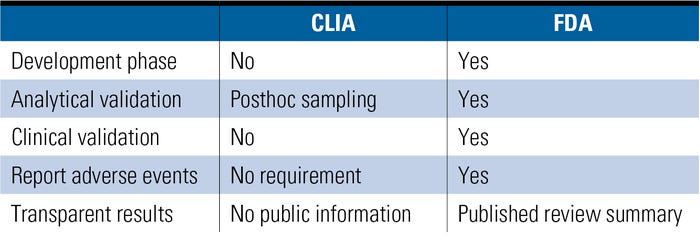

Table I. (Click to enlarge) A comparison of FDA and CLIA regulatory elements for certain IVDs. |

The government plays a role in regulating the quality of genetic tests, but observers note that there are some important gaps (see Table I). Even Janet Woodcock, director of FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, agrees that the current structure of genetic test regulation is “not optimal.”

Significant Gaps in CLIA Regulatory Oversight

CLIA regulations are based (as required by statute) on the complexity of the test method; thus, the more complicated the test, the more stringent the compliance and oversight requirements. Under CLIA, three categories of tests have been established: waived, moderate complexity, and high complexity. Most genetic tests fall into the high-complexity category. However, as pointed out earlier in the Report of the Secretary Advisory Report on Genetics, Health, and Society, oversight of genetic testing is limited in several critical areas.8 These areas include the following:

? Current CLIA regulations do not specify particular procedures or protocols. Although CLIA requires all clinical laboratories, including genetic testing laboratories, to undergo inspections to assess their compliance with established standards, current regulations do not specify particular procedures or protocols. Rather, they require laboratories to ensure that their test results are accurate, reliable, timely, and confidential, and that they do not present the risk of harm to patients.

? Most genetic testing laboratories are not required by CLIA to perform proficiency testing. Such testing is an external assessment of laboratory competence, yet CMS only enforces the formal proficiency testing performance requirement for laboratories offering any of the 83 regulated analytes.

? Only analytical validity is fully enforced under CLIA, because CMS does not have authority under CLIA to enforce clinical validity. Analytical validity of a genetic laboratory test is a measure of how well the test detects what it is designed to detect. Clinical validity measures the extent to which an analytically valid test result can diagnose a disease or predict future disease.

? CLIA has no authority or mechanism for external review of the clinical validity and clinical utility of tests. Utility of a test is a measure of how useful test results are to the person tested.

? CMS has no authority to perform postmarket review or adverse-event reporting, safeguards provided in FDA’s medical device regulations. CLIA provides for biennial inspections of laboratories, but these inspections do not focus on the clinical performance records of the LDTs themselves.

Conclusion

Few human genes had been identified at the time CLIA was enacted. However, in the 20 years since, genetic testing has moved from the sidelines into mainstream medicine. Although initial research focused on rare diseases caused by a mutation in a single gene, more recent research has focused on the identification of genetic contributions to complex, multifactorial conditions such as cancer, diabetes, and heart disease. Identifying the genetic underpinnings for individual variation in response to treatment has sparked interest in targeted drug design (pharmacogenomics) and in identifying those genetic variants that may predispose an individual to an adverse or, conversely, to a particularly good therapeutic response.

The common denominator in all of these current and future applications of genetic research to human health is the tests used to identify genetic variations. As the complexities of genetic research emerge, new insight into the necessity to ensure safety and efficacy has become apparent. Significant gaps in regulatory oversight exist in CLIA’s regulation of IVDMIAs, and they must be addressed.

FDA’s decision to issue a guidance document pursuant to the “least burdensome” provisions appropriately considered the costs and benefits of available regulatory alternatives and complied with good guidance practices. Indeed, FDA extended the comment period twice and held a public meeting, and the revised draft guidance addressed many of the concerns raised by stakeholders. FDA’s assertion of regulatory authority is not an attempt to create a new rule or to change an existing rule and therefore is not subject to the public rulemaking process under the APA. Rather, FDA’s goal is to address the gaps in regulatory oversight of IVDMIAs to ensure the safety and efficacy of these tests in the most cost-efficient and least burdensome way possible.

References

1. B Malone, “Healthcare Reform: What’s At Stake for Labs?” Clinical Laboratory News 35, no. 7 (July 2009).

2. “Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988: How to Assure Quality Laboratory Services,” Center for Medicare Advocacy. Available from Internet: www.medicareadvocacy.org/QualOfCare_CLIA.pdf.

3. Federal Register, 57 FR:7002, February 28, 1992; 68 FR:64350, November 13, 2003.

4. Draft Guidance for Industry, Clinical Laboratories, and FDA Staff—Multivariate Index Assays (Rockville, MD: FDA, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, 2007).

5. Washington Legal Foundation’s Citizens Petition. September 26, 2006. Available from Internet: www.wlf.org/upload/Clinical%20Labs-%20FDA%20Citizen%20Petition.pdf.

6. Federal Register, 58 FR:51,735, September 30, 1998.

7. Administrative Procedures Act, Title 5, USC Chapter 5, Sections 511–599. Available from Internet: http://usgovinfo.about.com/library/bills/blapa.htm.

8. U.S. System of Oversight of Genetic Testing: A Response to the Charge of the Secretary of Health and Human Services Report of the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Genetics, Health, and Society, April 2008. Available from Internet: oba.od.nih.gov/oba/SACGHS/reports/SACGHS_oversight_report.pdf.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like