February 1, 2007

MOVERS AND SHAKERS 2006

Since their introduction to the U.S. market in 2003, drug-eluting stents have been the most lucrative medical device. But that status was threatened in the past year when several studies showed that they are more likely than bare-metal stents to cause blood clots in certain patient populations.

|

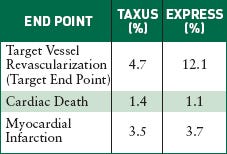

The U.S. Pivotal Study Taxus IV compares Boston Scientific's Taxus bare-metal stent with its Taxus Express paclitaxel-eluting stent nine months after implantation. |

Over the summer and fall of 2006, conferences in the cardiovascular world were dominated by drug-eluting stent discussions. The naysayers got so vocal that FDA convened a special meeting of its Circulatory System Devices Panel to look into the safety issues of drug-eluting stents and recommend any actions the agency should take.

The panel determined that when used as approved, drug-eluting stents are safe and effective, and their benefits outweigh their risks. However, at least 60% of the time, they are used off-label, on patients sicker than those who participated in clinical trials. For such real-world patients, there is not enough data to conclusively determine whether drug-eluting stents are too risky for them. (A number of studies on those kinds of patients have commenced within the past year, but results won't be known for a few more years.)

So all the panel could suggest is for doctors to be cautious about using drug-eluting stents on high-risk patients, and to consider prescribing anticlotting drugs for longer than what Johnson & Johnson, maker of the Cypher stent, and Boston Scientific, maker of the Taxus stent, have recommended.

The meeting and the discussions that preceded it are not likely to cause much drop-off in use of drug-eluting stents, as cardiologists are now aware of the issues, experts said.

“I think the benefits outweigh the risks for most situations,” says Neal Kleiman, MD, director of cardiac catheterization at Methodist DeBakey Heart Center (Houston). “The data are pretty good for drug-eluting stents, including safety, though there are still some questions. I don't think FDA needs to do anything different, at least right now.”

But Patrick Driscoll, president of MedMarket Diligence (Foothill Ranch, CA), believes that “FDA is not being as aggressive as it should be. It is too beholden to industry. It takes major events to prompt action from it.”

|

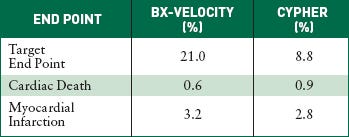

The U.S. Pivotal Study Sirius compares Cordis's Bx-Velocity bare-metal stent with its Cypher sirolimus-eluting stent. The target end point includes cardiac death, myocardial infarction, and revascularization after nine months of implantation. |

Another force at work, he says, is that J&J and Boston Scientific were too slow to acknowledge the problems because “when you invest in a $5-billion market, that gives you a lot of reasons to protect the status quo.” Quicker action may have spared some of the negative publicity and slowed the rate of doctors who decided to go back to using bare-metal stents, he says.

Michael Drues, PhD, president of Vascular Sciences, who has served as a consultant to a number of cardiovascular device companies, says the backlash was fairly predictable.

“I and a small number of other people were talking about these exact issues more than five years ago,” he says. “Nobody [from industry] listened. They continued to line up and drink the Kool-Aid.” His message has been that materials such as metals and polymers are inherently hostile to human cells. He says that device companies need to do a better job of assessing their implantable devices' effect on human biology, and designing around it.

“My biggest concern is that this [backlash] might make it more difficult for future development efforts for combination products, when we'll get to some really advanced stuff,” Drues says.

What is causing the clotting? Nothing has been proven yet. Many have suggested that it may have to do with the polymers on the stent that elute the drug. They remain inside the body after the drug is gone and may not be well tolerated by human cells.

Drues suggests that it may have to do with the drugs. (Cypher elutes sirolimus, a drug developed to help in kidney transplants; Taxus elutes paclitaxel, a drug developed to fight cancer.) “The drugs we are currently using to inhibit restenosis essentially inhibit all cell division,” he says. “The problem is that they are not selective. We want to discourage the production of certain cells, but we also want to encourage endothelial cells to proliferate. They help the body adapt to the stent and have no effect on blood flow.” But inhibiting all cell division and enabling the stent to stay in the middle of the artery may be inhibiting blood flow, he says.

Now that the extent of the problems are known, sales of drug-eluting stents have likely bottomed out and should improve from here, says Thomas Gunderson, senior healthcare analyst for Piper Jaffray & Co. “There will be a gradual increase in the use of drug-eluting stents going forward,” he says. “How much, remains to be seen.”

And, it is hoped, industry will figure out what's causing the problems before the next generation of drug-eluting stents hits the market. It had better, says Gunderson, because “the next generation will be looked at less for effectiveness and more for safety.”

Copyright ©2007 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like